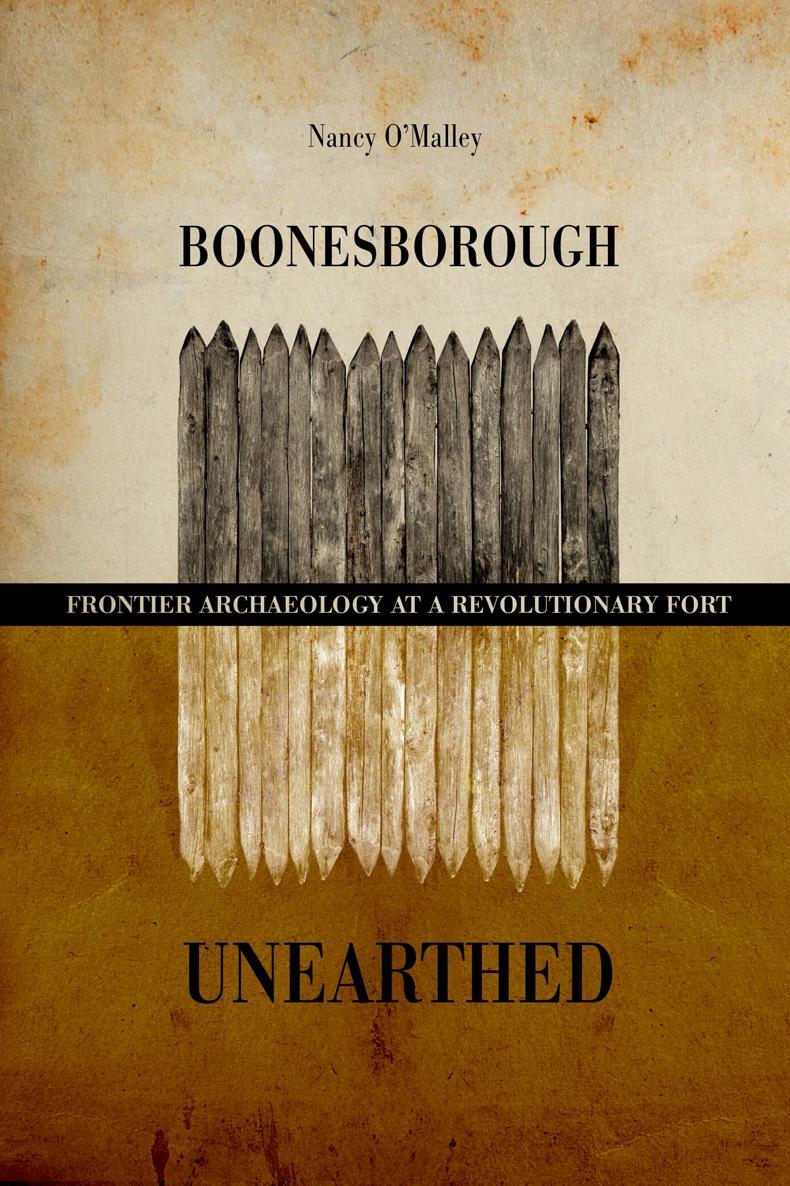

BOONESBOROUGH UNEARTHED

BOONESBOROUGH UNEARTHED

Frontier Archaeology at a Revolutionary Fort

Nancy OMalley

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

The Fort Boonesborough Foundation generously donated funds to support the publication of this book.

Copyright 2019 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, images are courtesy of the University of Kentucky.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-7761-8 (paperback : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7763-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7762-5 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of University Presses |

For my readers, who keep the memory of Fort Boonesborough alive

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figures

Table

PREFACE

B oonesborough was founded by Richard Henderson and his Transylvania Company partners in 1775 as the envisioned capital of a new colony more than two hundred miles west of the nearest settlements. The companys venture was an audacious attempt to create a colony governed under a proprietary model that circumvented a royal proclamation prohibiting settlement beyond the Appalachians. In claiming land obtained by an illegal purchase from the Cherokees, the company violated the terms of the Virginia charter. Moreover, the timing of the enterprise coincided with the American colonies War of Independence (17751783). The convergence of the Transylvania Companys ambitions and the inception of a revolution created a unique situation that demanded a creative response. Out of that need, Fort Boonesborough was born. Wartime hostilities necessitated the construction of a defensible fort composed of log cabins and stockade cobbled together to house and protect settlers from attack. From this humble origin Fort Boonesborough became an important site in the intertwined stories of American beginnings: westward expansion and the War of Independence.

Despite the forts early importance in the unification of the American colonies into one independent country, it was abandoned after the end of the Revolutionary War and the town planned at the site did not flourish. The town lots were eventually bought up by a handful of landowners who converted them to large farms. A small resort retained the name as an attraction for guests who came to fish, swim, and be entertained.

Yet the memory of the fort and its significance in the history of Kentucky and the nation did not entirely fade. Since its establishment in the 1960s, Fort Boonesborough State Park has memorialized the site as one of the most important early settlement sites in Kentucky and a key point of defense on the western front during the American colonies fight for independence from England. Park visitors can tour a replica of the fort to learn about the people who lived there and even visit the site of the fort itself, marked by a monument and a memorial wall erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). But by the mid-twentieth century a persistent belief spread among many local residents that the monument marked the wrong site. Which story was true?

In 1987 I was asked to find the answer. The quest for the truth led me on a journey that extended over thirty years of archival and archaeological research. I began with the original question of the sites actual location and expanded to explore more questions about the site itself: How much of it was preserved, what archaeological evidence did it contain, and what could that archaeology tell us? When I began the Fort Boonesborough project, I already had researched the defensible residential stations established in Kentucky by late eighteenth-century Euro-American settlers and their slaves on land claimed under Virginia law. The large public fort at Boonesborough, another part of the early settlement story, had never been examined from an archaeological perspective. Archaeology offers a unique means to assess the cultural past, and historical archaeology focuses its attention on physical evidence such as artifacts and cultural features (e.g., structural foundations, storage pits, and other physical evidence in the ground) coupled with archival sources to reconstruct what a site looked like, who lived there, and how they lived. This book brings together all the archaeological data that have been gathered about the site of Fort Boonesborough, one of only a handful of large forts that were constructed in Kentucky during the Revolutionary War. The site is the only major colonial fort in Kentucky that still exists as an archaeological site.

The impetus for this archaeological project to confirm the exact location of Fort Boonesborough had unusual origins. In 1985 Jim Kurz, who worked in the economic development and regional planning field, was competing in the Bluegrass Triathlon. As Jim put it in an unpublished account, The past is important to me. Sometimes when I least expect it, something from the past reaches out to me, captures my attention, and my mind turns back to days gone by. In the midst of completing the swimming portion of the triathlon, part of his mind was occupied by thoughts of Daniel Boone and his fellow settlers and the stories of their establishment of Fort Boonesborough. A graduate in American history at Eastern Kentucky University, Jim knew of the DAR monument that marked the traditional site of the fort at the state park in Madison County. He was also aware of the local belief that the actual

A visit to Martins Hundred, the site of an early plantation in Virginia, and an encouraging letter from Colonial Williamsburgs noted archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume helped him formulate a plan, and he began looking for funding. Jim Kurz is an energetic and enthusiastic person who throws himself wholeheartedly into worthwhile projects. He identified four possible sources for funding and support: the Madison County Historical Society, the Fort Boonesborough State Park Association, the Kentucky Heritage Council, and the State Department of Parks. He wrote letters, visited organizations and influential people, and pitched his idea tirelessly. Along the way he garnered support and made useful contacts. I was one of these contacts, and after listening to Jim, I enthusiastically offered my professional services to the project. Following a luncheon at which Jim emphasized the potential economic benefits and I stressed the positive aspects of a public archaeology project, all four of the sources Jim had identified boldly pledged the necessary funding. I am indebted to Jim for getting the ball rolling, and I am grateful to our initial four funding sources for seeing the value of the project and providing the funds that made it possible.