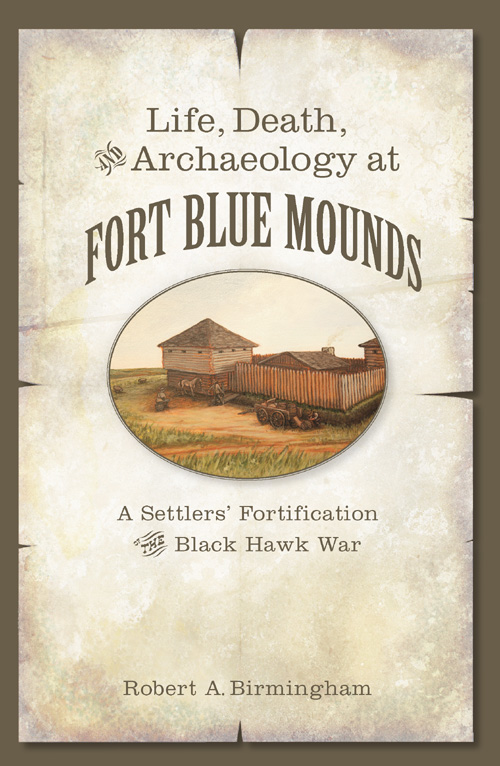

Life, Death, and Archaeology at

Fort Blue Mounds

A Settlers Fortification

the Black Hawk War

Robert A. Birmingham

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

Electronic edition 2012 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant from the D.C. Everest fellowship fund.

For permission to reuse material from Life, Death, and Archaeology at Fort Blue Mounds, 978-0-87020-492-0 or 978-0-87020-596-5, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsinhistory.org

Photos and illustrations are from the author unless otherwise specified.

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Cover art from the Friends of the Military Ridge Trail Interpretive Center Mural in Ridgeway, Wisconsin. Project artist: Ingrid Kallick; project historian: Tom McKay. Funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Photo by Mark Fay.

Designed by Diana Boger

16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has catalogued the printed edition as follows:

Birmingham, Robert A.

Life, death, and archaeology at Fort Blue Mounds : a settlers fortification of the Black Hawk War / Robert A. Birmingham.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-492-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Fort Blue Mounds (Wis.) 2. Excavations (Archaeology)Wisconsin)Fort Blue Mounds. 3. Frontier and pioneer life)Wisconsin)Fort Blue Mounds. 4. Black Hawk War, 1832)Antiquities. I. Title.

F587.D3B57 2012

977.583--dc23

2012018868

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book tells the dramatic story of Fort Blue Mounds during the Black Hawk War, describes the search for and discovery of its remains, and offers insights as to what the historical and archeological research conveys about life during the war and on the frontier at the time. The larger story of the Black Hawk War is nearly incomprehensible to us today since it is far removed in time, circumstance, and worldviews. The past is a foreign country, as once noted by British novelist L. P. Hartley. It is now difficult for us to put ourselves in the place of those Indian people risking their lives against all odds to retain their lands and culture; or in the place of those who would deprive an entire people of their homes and their very lives in order to secure their own place in a new nation; or in the place of frightened settlers who sought only to begin new, productive lives for themselves and their children, facing the great challenges each day brought. However, smaller stories like those of the Blue Mounds community offer us a more intimate journey into the foreign land of the past as were guided by the eyes and hands of those who lived there. The archaeological research even provided participants with an opportunity to literally touch history.

I am grateful to the many volunteers who devoted weekends to excavating the site through heat, cold, rain, and worms. I enjoyed their company thoroughly, and they performed to the high standards of professional archaeology. These are Ben Anderson, Linda Anderson, Neil Anderson, Amy Bandle, Dave Beard, Brian Birger, Nancy Birmingham, Barbara Bray, Eileen Carlson, Barbara Chattergee, Mik Derks, Bruce and Wesley Ellerson, Jane and Virgina Evans, Harvey Fedler, Tom Fey, Bill Figi, Ellen Figi, Nora Figi, Bruce Fischer and family, Adam Fleming, Terry Genske, Stephen Gilbert, Richard Gill, Bob Halseth, Colleen Hermans, Angela Horn, Gary Howards and family, the Hull family, Jan Jensen, Allan Korbitz, Craig Malven, Norm Meimholz, Jerry Minnich, Joe Monarski, Jessica Nowicki, Rebecca Perkins, Helene Pohl, Al Schmidt, Jennifer Scot, Steve Steigerwald, Tom Waddell, Bill Wamback, Pat Wirtz, Harley Young, Bob Zimmerman, and Boy Scout Troop 34 of Madison.

Henry Eckel, Jessy Straubhaar, and Reini Straubhaarowners of surrounding landsgraciously allowed access to the site and helped the project in many material ways. Valonne Eckel, who lives in a house adjacent to the site, put up with a yard full of vehicles during many summer weekends and also donated artifacts she found as a child on the fort site. Full-time and part-time Wisconsin Historical Society archaeology staff, mainly students at the timeWilliam Gartner (PhD, University of WisconsinMadison, 2003); John Hodgson and Tom Ritzenthaler (University of WisconsinMadison); John Orie (Oneida Nation); and Amy Rosebrough and Robert Simpkins (PhDs, University of WisconsinMadison, 2010)assisted in various ways in excavation, research, and analysis. My son, Kevin Birmingham, assisted me with some of the photography and in many other ways.

Steve Kuehn, now of the Illinois Transportation Archaeology Program, analyzed animal bone recovered during the excavation while working for the Wisconsin Historical Society Museum Archaeology Program. Bob Braun of the Old Lead Mine Region Historical Society and Bob Mazrim of the Illinois Transportation Archaeology Program shared their expertise on period artifacts and history. After I retired from the Wisconsin Historical Society in 2004, the institution provided me with access to the collections and extended many professional courtesies.

Doing archaeology and writing history offer many opportunities for error, and I alone take responsibility for any errors in fact or interpretation that may have crept into this book.

Preface

During the Black Hawk War of 1832, settlers of Blue Mounds in Michigan Territory, now the state of Wisconsin, formed a volunteer militia, built a fort, and lived there for nearly three months while enduring anxiety, deprivations, and violent death. The conflict began when the Sauk warrior leader Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi River from what is now Iowa with a band of approximately 1,100 men, women, and children to continue life on ancestral lands in Illinois that had been claimed by the United States government through a controversial treaty. Federal troops and state and territorial volunteer militia tried to stop the defiant Black Hawk and return his people to the land they had been removed to west of the Mississippi. Blocked from resettling, the Indian band moved northward, chased by the military and engaging in short but deadly skirmishes. War parties from Black Hawks band and some warriors from other tribes launched attacks on settlers and settlements, creating panic throughout the Upper Midwest.

Messages and rumors concerning the northward movement of Black Hawks band, along with deadly encounters and attacks, had reached the small lead-mining community of Blue Mounds, located thirty miles west of the present-day state capital of Madison. The settlers hastily erected a fort in May 1832, one of at least seventy-eight temporary fortifications built by the panicked white population in southwestern Wisconsin, Illinois, and beyond.

The frontier settlers of Blue Moundsmostly lead minersfeared the worst, and, indeed, the occupants of the fort found themselves engulfed by the conflict. Because of its strategic location relative to Black Hawks movements, the fort served as a center for militia and US Army activities.