This edition is published by Muriwai Books www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books muriwaibooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Muriwai Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

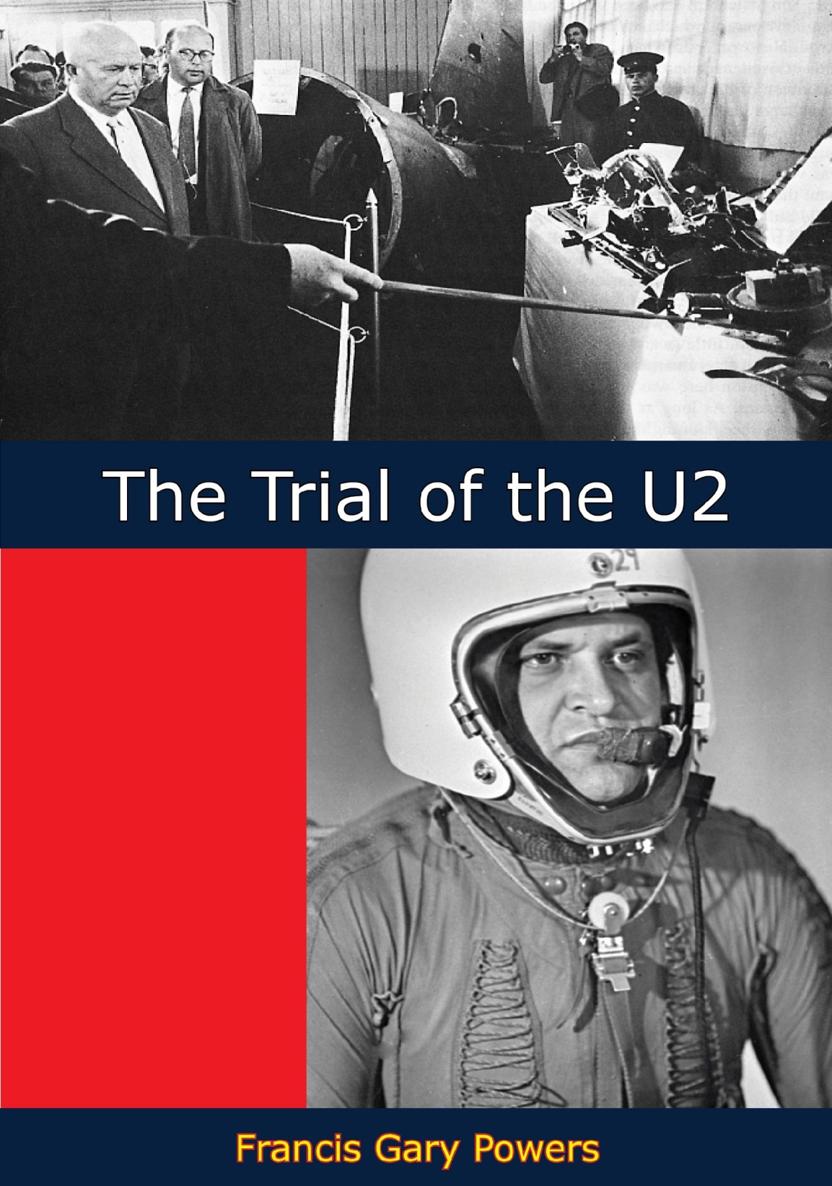

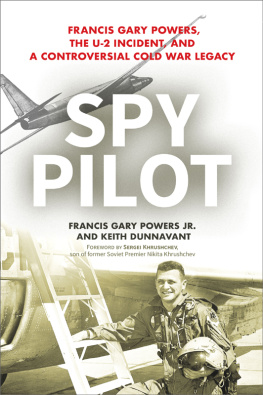

THE TRIAL OF THE U2

EXCLUSIVE AUTHORIZED ACCOUNT

OF THE COURT PROCEEDINGS OF THE CASE OF FRANCIS GARY POWERS

HEARD BEFORE THE MILITARY DIVISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.S.R. MOSCOW AUGUST 17, 18, 19, 1960

Introductory Comment by

HAROLD J. BERMAN

INTRODUCTION BY HAROLD J. BERMAN {1}

I.

This book contains the official record of the trial of an American airplane pilot, Francis Gary Powers, for espionage, in the Military Division of the Supreme Court of the USSR on August 17-19, 1960. The record was released, in English translation, by the Soviet Government. This is, then, the official story of the trial, containing, in full, the indictment, the testimony presented in court, the closing speeches of the prosecutor and the defense counsel, the last word of the accused, and the verdict of the court. The book also contains some pictures taken during the course of the proceedings by the Soviet news agency TASS.

Writing only two weeks after the close of the trial, one can hardly hope to put it in proper historical perspective. That it has generated an intense interest is apparent from the enormous publicity given to it in the press and radio of virtually all countries. Yet its significance is by no means clear. Perhaps, like the Czech trial of the American journalist William Oatis in 1951, it soon will be recorded as an almost forgotten episode in the cold war. Yet there are elements in this case which seem to give it a more lasting importance. It dramatizes some of the most acute problems of international relations in our time.

Powers presented himself as a very unconventional spy. According to his testimony at the trial, he had volunteered for the United States Air Force shortly after graduating from a small mid-western college, and he had contemplated becoming a commercial air pilot after his term of enlistment was over, but found he would be too old and not acceptable for that. Approached by the Central Intelligence Agency in 1956, at the age of 27, he took a civilian job requiring him to make high altitude flights along the Soviet border for the purpose of collecting radar or radio information, at a salary of $2500 a month. This, he said, was approximately the same salary as a first pilot or captain of an airliner, and he felt very lucky to get such a job. He was trained to fly a Lockheed U-2a small, light, unarmed plane designed for altitudes of 60,000 to 68,000 feetand to turn levers on and off over specified places. He knew that equipment was installed on the plane for purposes of photographing objects on the ground and recording radar signals, he testified, but he had never seen the equipment. We were allowed to know only what was necessary for our work. He was just a pilot. When he was assigned the job of flying across the Soviet Union from Pakistan to Norway, he was scared, but he could not refuse to do it because, as he put it, By refusing I would have been considered a coward by my associates and it would have been a non fulfillment of my contract [with the C.I.A.]. His fears were somewhat calmed by the assurance of his Colonel that Soviet rockets could not reach him at 60,000 feet. When in fact he was forced down over Sverdlovsk, he apparently was willing to tell his Soviet captors all he knewwhich apparently was not muchabout the intelligence activities in which he was engaged.

This, then, was no Rudolph Ivanovich Abel, Colonel of the Soviet K.G.B. (Committee on State Security), who was convicted of espionage by a federal district court in New York in 1957 and sentenced to 30 years imprisonment. Abel was charged with having for eight years headed a spy ring in the United States for the purpose of collecting and transmitting to the Soviet Government information relating to arms, equipment and disposition of United States Armed Forces and to the atomic energy program of the United States. Though grilled ceaselessly by the F.B.I. for five days without sleep, and then daily for three weeks, Abel gave no information concerning his activities as a Soviet agent. He pleaded not guilty, did not take the stand to testify, and has never admitted that he was a spy.

Powers, on the other hand, pleaded guilty, took the stand, described his activities in detail, and admitted that he was a spy. He gives the impression simply of one of thousands of ordinary citizens who happen to work for C.I.A.a technician, a pilot, but hardly a spy! It is perhaps the fact that the image of Francis Gary Powers seems no different from any other airplane pilot who might have been born in Burdine, Kentucky, 31 years ago (his 31 st birthday fell on the opening day of the trial), which gives the case a certain initial significance. What is espionage? Is it evil? Is this the kind of person against whose activities espionage laws are passed? Are our concepts of espionage suited to a space age?

If Powers behaved unconventionally for a spy, the United States Government behaved even more unconventionally for a government charged with having commissioned a spy. It admitted that it had!

Spies, states a leading treatise on international law (Oppenheims International Law, 8 th ed., 1955, vol. 1, p. 862), are secret agents of a State sent abroad for the purpose of obtaining clandestinely information in regard to military or political secrets. Although all States constantly or occasionally send spies abroad, and although it is not considered wrong morally, politically, or legally to do so, such agents have, of course, no recognised position whatever according to International Law, since they are not official agents of States for the purpose of international relations. Every State punishes them severely if they are caught committing an act which is a crime by the law of the land, or expels them if they cannot be punished. A spy cannot legally excuse himself by pleading that he only executed the orders of his Government, and the latter will never interfere, since it cannot officially confess to having commissioned a spy.

Such is the black-letter rule: a government cannot officially confess to having commissioned a spy. The Soviet Government has certainly abided by this accepted international standard! It has never given the slightest official indication that it even knows of the existence of Rudolph Abel. When asked by American correspondents, in connection with the U-2 incident, whether it is not true that Soviet spies are active in various countries, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko replied that the Soviet Government does not engage in such activities. According to international practice he cannot say otherwise.