INTRODUCTION

I am often asked why I developed the Black Holocaust Exhibit and how I conceived of the idea. Relating the pain of my people was never a part of my career plans. I never sat down and said, let me build a collection that speaks to the treatment Africans received under slavery. It was more as though I was being called by the ancestors to tell their stories. Countless instances guided me to this project: documents I hesitated to purchase, I bought; reference books were purchased and forgotten, and then reappeared; people who could offer insight came into my life just when I needed them. These repeated occurrences made me feel that this was a special project, one foretold by the ancestors generations ago. It was a resurrection of the stories that the enslaved wanted to be told, only awaiting a vessel through which they could speak.

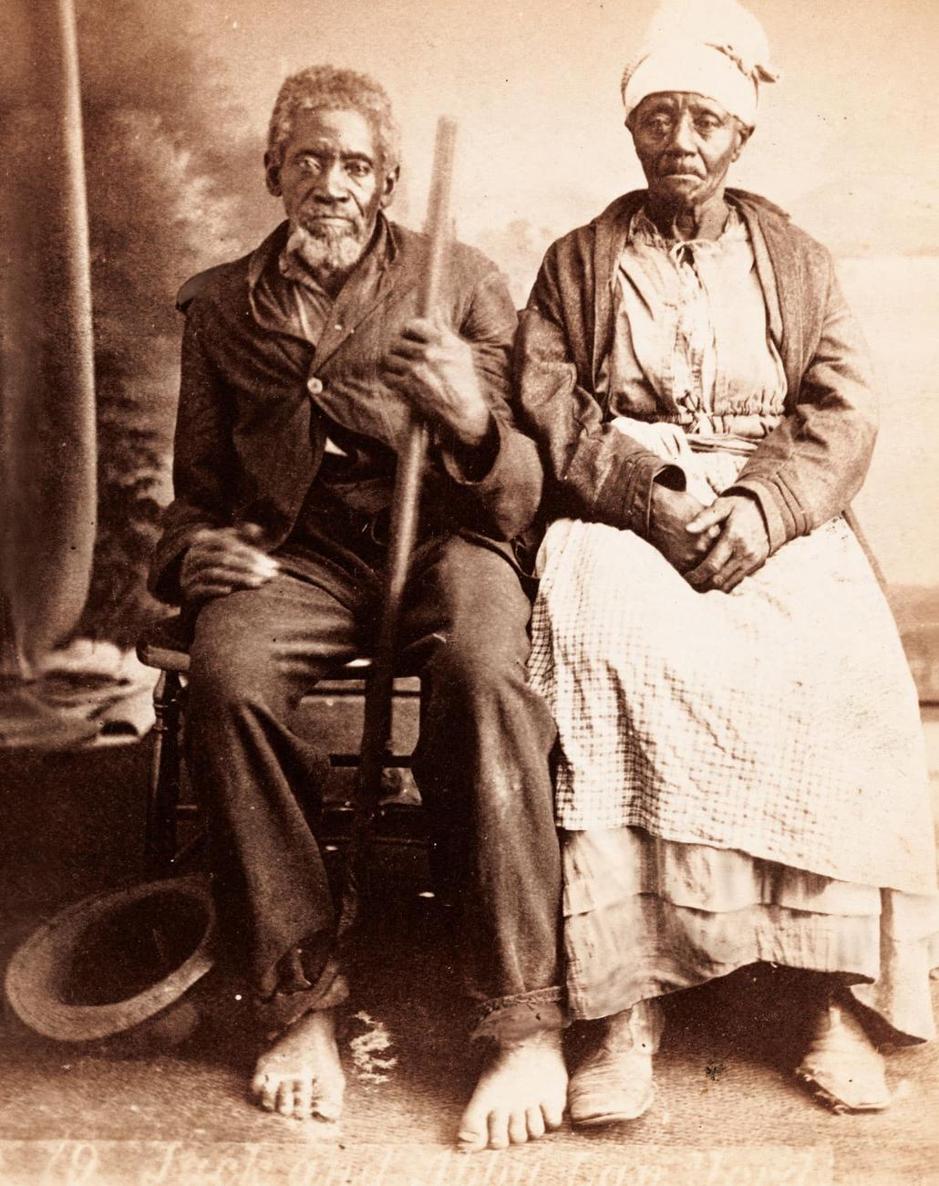

Lest We Forget is a tribute to those whose lives are told through the documents youve seen and read. It is a tribute to enslaved men and women, bought and sold, whose names appear briefly, jotted down by a slaveholder, then filed away in boxes in dusty archives or copied onto lifeless microfilm. The exhibit and this book give voice to those whose cries and words were silencedyoung children torn from their parents, men and women swapped or given as gifts, old people broken and appraised as worthlessacts you may have heard or read about in textbooks, but never fully understood or felt until now, when you hold an actual document in your hands.

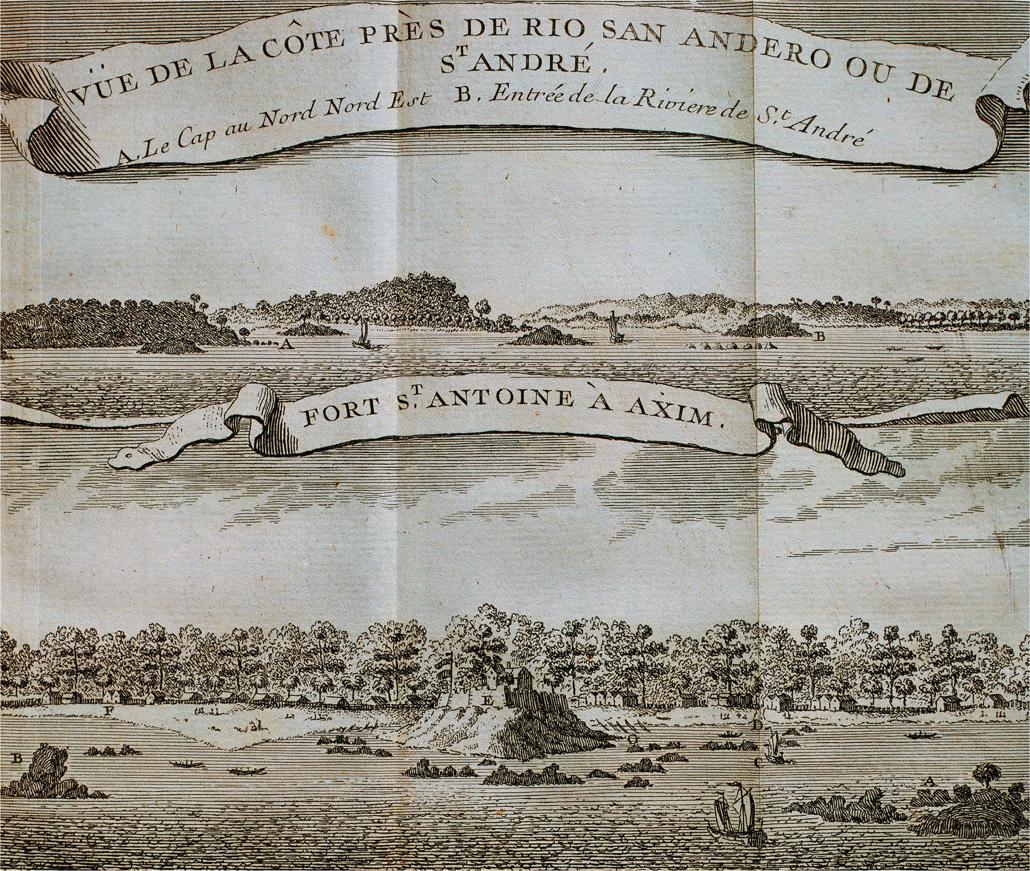

View of the coast near Saint Andrew river and the Fort Santo Antonio, 16th century, in Aximthe Dutch Gold Coast. Captured for the Portuguese and later occupied by the British. Drawing by William Smith, 1726.

Some may argue, Why bring up such a painful period in our countrys history? Some may feel that they have no apology to make, as neither they nor their forefathers were slaveholders. Others may feel dredging up tales of Africans in chains humiliates the race. When one speaks openly of slavery, the nation tightens.

Perhaps there is an uneasiness because the attitude that undergirded slavery exists today. Prejudice still looms. America is still a divided nation. America was built on the backs of enslaved Africans; it still suffers internal turmoil because it never righted that wrong, never truly tore down the walls of racism.

There is a subtle, strong power in our words and language. Many historians today use the adjective enslaved instead of the noun slave to describe their position at that time instead of limiting or beholding them to that position. Throughout, depending on the context, we will use both terms wherever most appropriate to not interrupt the conversation.

I hope this book gives those who read it a better understanding of the human drama of slavery and of the human spirit that would not be broken. From 1619 to 1865, Africans in America were enslaved. Today, my people are civic, political, and religious leaders, businessmen, judges, physicians, teachers, artists, inventors, recipients of the Nobel Prize, and more. Such great strides against a continual tide of resistance attest to my peoples remarkable will and to their undying faith in the sovereignty of a higher power. We owe much to our forefathers; their sturdy backs have been the bridges that have brought us thus far. To them we say thank you. Their sacrifices we shall never forget.

Velma Maia Thomas

Africa Before the Slave Trade

E uropeans have long considered Africa to be a strange and mysterious place. Many called it the Dark Continent, but to Africans and the enlightened Europeans who came to know it, Africa was a land kissed by the gods.

Africa is the home of the Nile, the worlds longest river; the Sahara, the worlds largest desert; and Mount Kilimanjaro, one of the worlds highest mountains. It is the home of Egypt and Timbuktu, cradles of civilization, commerce, medicine, mathematics, and knowledge. It is at the birthplace of all life; the land where human life began some four million years ago.

Before the Europeans came, my people were known by their indigenous names. They were the Bambara, the Mende, the Ewe, the Akan, the Kimbundi, the Zulu, the Hausa, and the Tesojust to name a few. Africans called their empires the Songhai, Mali, Katsina, and Kanem-Bornu. Before my people spoke English, French, Portuguese, and Spanishlanguages of their European conquerorsthey spoke Twi, Fula, Hausa, Shona, and a thousand other African languages.

This was before the invasion of the Europeans. Before Africa was theirs, she belonged to the black man. It was not until the fifteenth century, when European powers entered Africa, first for gold, then for people to enslave, that the face of Africa changed. They called our lands the Gold Coast, the Ivory Coast, the Grain Coast, and soon, the Slave Coast, labeling them according to the riches they could exploit. In 1884, after 200 years of reaping the economic benefits of enslaved African labor, European powers met in Berlin to decide who would control the land, setting the stage for the scramble for Africa. They carved Africa into pieces among themselves, claiming its wealth and exerting their military and political power. It would not be until the 1950s, through armed struggle and resistance, that Africa would again be ruled by Africans.

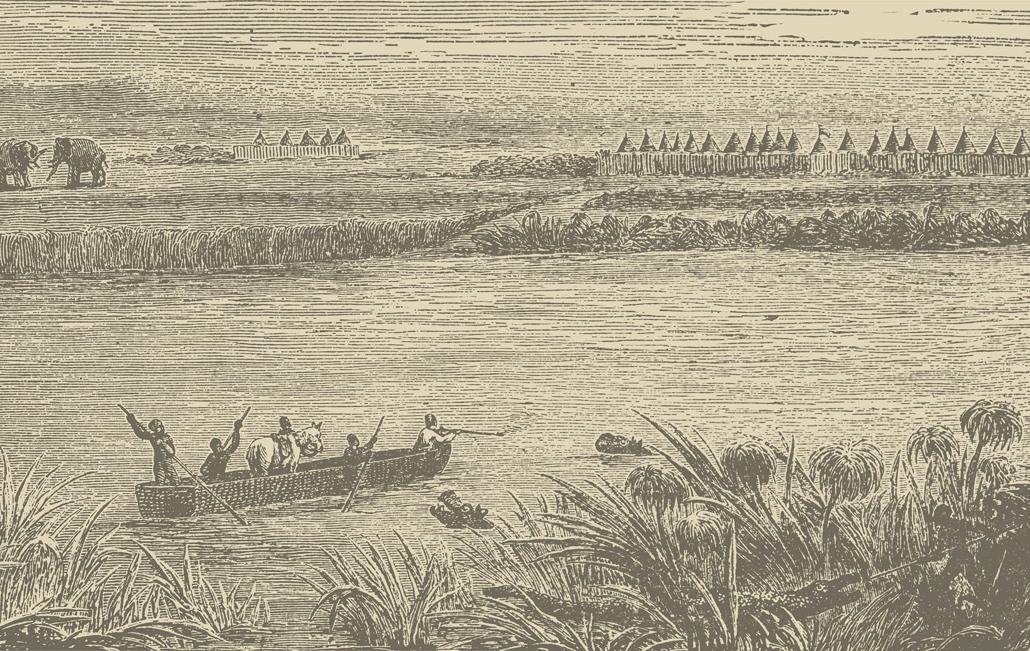

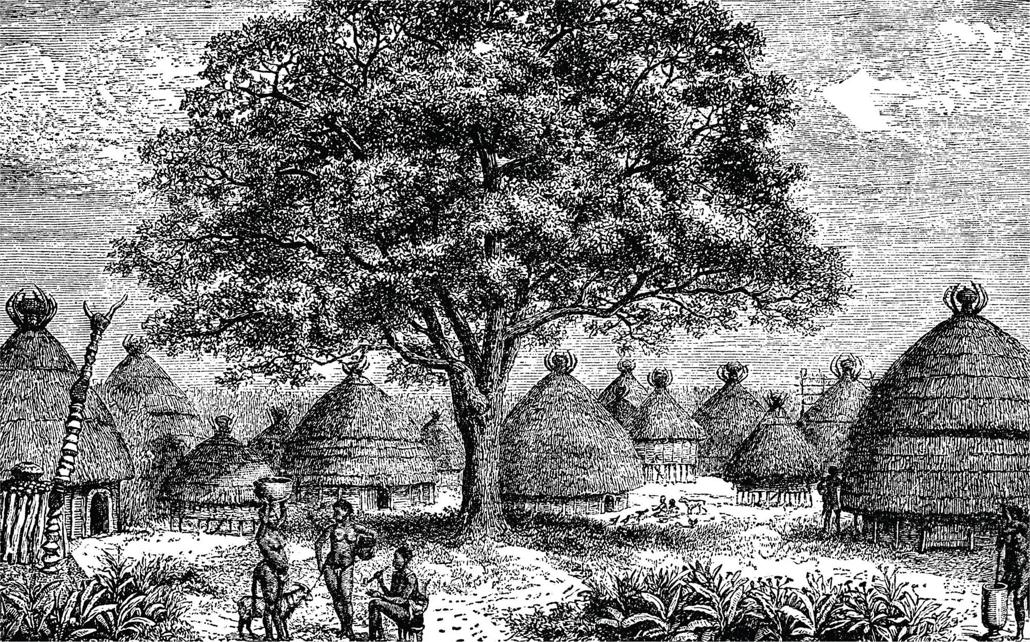

A 19th-century engraving of an Africa village with huts, from a book titled The Worlds Wonders as Seen by the Great Tropical and Polar Explorers, published in London, 1883.

Why should one learn about the changing history of Africa? Because the slave trade and colonialism halted Africas growth and development. Africa, the birthplace of mankind, the giver of religion, civilization, and science, the dark continent from which the light of knowledge emerged, is a great land. If you want to know the Africa of our ancestors, look to Africa from the beginning of civilizationthe Africa before the arrival of the Portuguese and other foreign invaders.