Preface

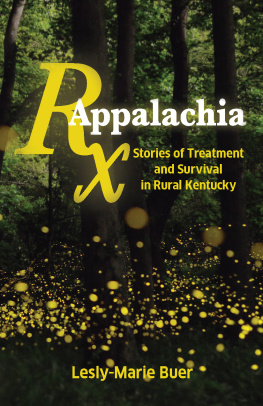

By every socioeconomic measurement, the area of Eastern Kentucky that I covered for the Louisville Courier-Journal in the 2000s is Appalachia at its most compelling and extreme. I was the last major metropolitan newspaper reporter based in those coalfields, and I wanted to write this book to provide what I believe is the most complete account to date of one of the most mythologized and least understood places in the country.

It took me five years of chronicling Eastern Kentucky as a reporter and another fifteen years of thinking about and returning to those stories, in my dual role as a writer and the husband of a Harlan County coal miners daughter, to understand why we still dont understand Appalachia.

There was hope after the 2016 presidential election that we might be moving toward a more nuanced view of Eastern Kentucky when, for a moment in time, the countrys scholars and storytellers begrudgingly moved past looking at the region merely as an object of perverse curiosity. All of the credit for this hint of progress went to one man: Donald Trump. In the wake of Trumps improbable ascendancy to the White House, writers and commentators, almost exclusively from Blue State America, set their gaze on Appalachia to ask variations of the same question: How could you have let this happen? Forget that Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin were the states that swung the election to Trump. Forget that most Eastern Kentucky counties gave previous Republican presidential candidates John McCain and Mitt Romney roughly the same level of support that they gave Trump. And forget that Bernie Sanders trounced Hillary Clinton by a two-to-one margin in most parts of Eastern Kentucky in the 2016 Democratic primary. The experts pronounced that Appalachia held the key to explaining Trump and Trumpism. For the first time, Appalachians and what they thought actually mattered to the country at large. Or that was the premise, at least.

This wave of national interest in Eastern Kentucky was predicated on a misinterpretation of voter registration figures. It is true that registered Democrats far outnumber registered Republicans in many counties in the region, but those numbers are a vestige of mid-twentieth-century social dynamics that do not represent the political leanings of today. If reporters left their bubbles in the hopes of discovering large clusters of people who voted for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016, they simply went to the wrong place. Of the 206 counties nationwide that fit that description, 31 are in Iowa and 23 are in Wisconsin. Only one, Elliott County, is in Kentucky. In 2020, Elliott County again came out in force for Trump, who carried every Kentucky county but two, Jefferson and Fayette.

In the absence of anything more broadly applicable to a dissection of electoral politics, most of the resulting Eastern Kentuckyset stories relied on tired old tropes about alienation from government and parochial worldviews. Welcome to Trump Country, everyone. Nothing more to see here. Time to catch that flight back. Left unchallenged, that bogus narrative has persisted, with national publications ruminating on a split partisan identity in Eastern Kentucky that doesnt exist.

Unlike after the 2016 election, no one in 2020 flocked to Eastern Kentucky seeking insight or votes. Only parts of Central Appalachia in key battleground states received any attention at all from the presidential candidates. Moon Township, Pennsylvania, became a regular campaign stop. For all the attention it was paid, Appalachian Kentucky might as well have been a region on the moon. The future of Central Appalachian coal jobs, a major theme of the 16 campaign, hardly got mentioned, mainly because Trump failed to deliver on his promise to revive the coal industry. So, instead, he tried to use Democratic opposition to fracking as a new Republican rallying point.

Yet there remains an undeniable symbolism to Eastern Kentucky, and it is one that both captures and transcends the troubled political climate of the day. But to grasp it, we need to get better at viewing the region in the framework of a larger American story about income inequality, generational poverty, and the lack of upward mobility. Only then will we start the demystification process.

When I think about the things I saw and documented in Appalachian Kentucky, I realize that this small swath of America with a population of around 700,000 offers tremendous insight into who we are and what we value as a nation. You cannot tell the story of a place as complex and contradictory as Eastern Kentucky in 800- or 1,200-word chunks written in inverted pyramid style, as I was once tasked with doing. That was a whiplash-inducing and at times overwhelming assignment. Coal mining could have been its own beat. The same applies to prescription drugs, poverty, religion, and culture. This book is my attempt to pull all of the strands together, to journey beyond the hundreds of newspaper bylines I accumulated, to capture the essence of a place that I observed for years and continue to revisit and reevaluate. The major events I chronicled for the Courier-Journal frame the narrative, but it is the material that didnt make it into the paper that I believe makes this more than just another crack at explaining Appalachia.

The book examines the economic and social experiment that created the power structure of modern-day Eastern Kentucky, a proxy for struggling regions everywhere, and traces how the dramatic events of the early years of this century impacted the region and influenced the soul of the nation as a whole. It also highlights the essential role of the journalist in writing the first rough drafts of history, especially now that newspapers have left Eastern Kentucky and places like it, leaving no one to tell some very essential stories.

The result is a story about drug epidemics, political violence, environmental degradation, and morality debates, but also about a seemingly laid-back rural culture where a large segment of the population is clinically depressed, about an area of natural beauty where the land has been stripped and the forests torched for amusement, and about a defining push and pull between fierce pride and a nagging sense of inferiority. Ultimately it is a story about how America and its institutions have failed Eastern Kentucky, but for better and for worse, how the people of the region have remained loyal to their idea of Americanism.