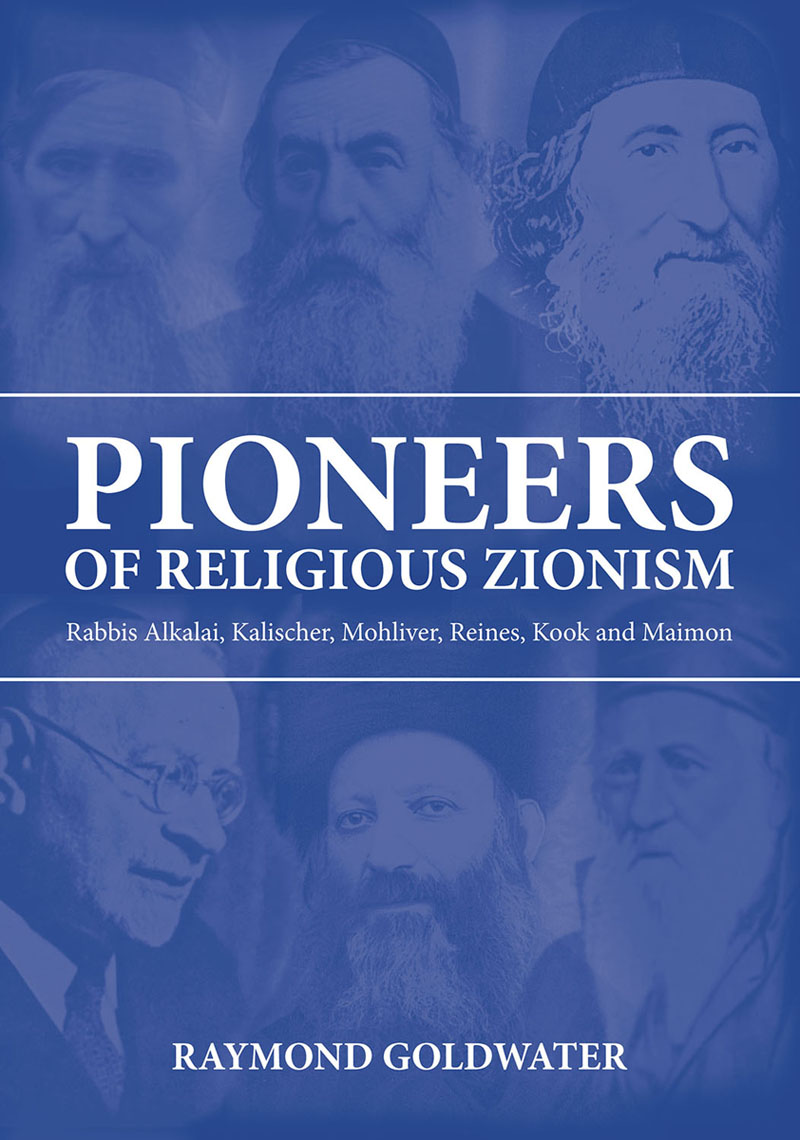

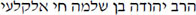

Pioneers of Religious Zionism: Rabbis Alkalai, Kalischer, Mohliver, Reines, Kook and Maimon

By Raymond Goldwater

Copyright 2020, 2009 by Raymond Goldwater

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright owner, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and articles.

First Edition

E-book ISBN 978-965-524-343-7

Hardcover ISBN 978-965-524-023-8

Photographs of Rabbis on the front cover courtesy of Mossad HaRav Kook, Jerusalem. From top left (clockwise): Rabbis Mohliver, Reines, Kalischer, Alkalai, Kook and Maimon.

Cover design by the Virtual Paintbrush

Urim Publications

P.O. Box 52287, Jerusalem 91521 Israel

www.UrimPublications.com

To my dear wife, Bella

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

T HIS BOOK DEALS with the life and thought of the six most important Zionist rabbis of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Yehudah ben Shlomo Alkalai (17981878), Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (17951874), Samuel Mohliver (18241891), Jacob Reines (18391915), Abraham Isaac Kook (18651935) and Judah Leib (Fishman) Maimon (18751962). These rabbis combined traditional Jewish life and thought with practical Zionism.

Alkalai, a contemporary of Kalischer and a leader of the self-governing Jewish community in the Land of Israel, was the prophet of modern religious Zionism. He developed the concept of teshuva as meaning both repentance and return to the Land of Israel, the combination of which would lead to the full redemption. Alkalai also wrote practical proposals for the return of the Jewish People to its land that foreshadowed future developments in Zionism.

As we shall see, rabbinic reaction to Alkalais ideas was mixed. Samson Raphael Hirsch rejected the basis of his ideas about resettlement of the Land of Israel and the full redemption which, in Hirschs view, could occur only by divine intervention. In addition, Rabbi Meier Auerbach, the head of the Ashkenazi Beth Din in Jerusalem, disagreed with Alkakis entire philosophy. Yet Alkalai was not only a theorist; he was also was a man of practical affairs. He sent his son to investigate conditions in the land of Israel and traversed Europe in order to raise funds to support the nascent settlements there.

Mohliver foreshadowed later developments within the Zionist movement by working with the secular Chovevei Zion group, for which he raised money and became spokesman to Jewish philanthropists. In order to relieve the strain in Chovevei Zion, Mohliver founded a spiritual center within the organization in order to spread the idea of settlement in Eretz Israel among the religious population. This center later became the Mizrachi Movement.

It is therefore a paradox that Jacob Reines, who founded Mizrachi as a religious party within the Zionist movement, rejected the concept central to the thought of Alkalai and Kalischer: that the purpose of settling Eretz Israel was to establish a self-governing community there in order to bring about the final redemption. Reines disagreed, believing that the redemption could only come about by divine intervention. For him, modern religious Zionism was a solution to the two great problems that world Jewry faced: assimilation and persecution. Consistent with this view, Reines was prepared to accept an offer by the British government of a Jewish national home in Uganda.

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kooks assessment of Zionism was quite different. For him, the acquisition and settlement of land in Israel was a halachic imperative. He felt that dissatisfaction with the secular nature of most settlements did not exempt the Jewish people from their halachic duty to develop the land.

Judah Leib Maimon became active in the Mizrachi organization. Under his leadership the Mizrachi Movement became the constant ferment that infused modern Zionism with the concept of the divine. He believed that the synthesis of holy and secular thus created would produce the vitality necessary to ensure the success of Zionism (Chazon ha-geulah, 184186). Through Maimons complete identification with the aims of Zionism and attachment to the whole of the Jewish people, he was able to persuade the Zionist leaders and, later on, the political leaders of the newly-created State of Israel to meet the basic requirements of traditional Judaism in its public life.

The lives and thought of Rabbis Alkalai, Kalischer, Mohliver, Kook and Maimon provided the philosophical, religious and practical basis for Zionism, and ensured that the Zionist movement and the Jewish state would not become disconnected from Jewish tradition.

Rabbi Yehudah Ben Shlomo Chai Alkalai

R ABBI Y EHUDAH B EN S HLOMO C HAI A LKALAI

(17981878)

Y EHUDAH BEN S HLOMO C HAI A LKALAI was born in Sarajevo, Bosnia in 1798. He spent his youth in Jerusalem, where he was influenced by Rabbi Eliezer Papo, himself a native of Sarajevo. He returned to Serbia as a young man where he eventually succeeded his father as cantor and teacher in Zemlin (Zemun), and he became the rabbi of the community at the age of twenty-seven. There he came under the influence of Rabbi Judah Samuel Bais, a founder of the Hibbat Zion movement, as his writings and articles in later years show clearly.

In order to understand Alkalais life and work properly, we must look at the events in Europe and particularly in Serbia, which formed both the backdrop and the stimulus for his philosophy and action. The French Revolution had stimulated both individuals and peoples to demand freedom to develop indigenous cultures and shake off the political shackles imposed by the Turkish and Austro-Hungarian empires. But this flowering of national and individual freedom benefited Jews intermittently at best. Although Jews supported the independence movements, they were still subjected to periodic expulsions from cities or villages, restricted in professions or business and, despite an 1860 decree emancipating all citizens, were not given full emancipation.

As a teacher, Alkalai soon realized the necessity of a dictionary and grammar textbook for the teaching of Hebrew, and his first book, Darchei Noam, which was published in Ladino in 1839, met this need. In this work, Alkalai gave many examples of the serious textual distortions that result from the imprecise reading of individual Hebrew letters. The vast majority of rabbis at the time regarded knowledge of grammar as unimportant despite the example of Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, the Vilna Gaon (17201797), whose revolutionary understanding of the Talmud and elucidation of the text stemmed in part from his deep knowledge of Hebrew grammar.

Darchei Noam also gives an indication of Alkalais views about the redemption of the Jewish People through the biblical and Talmudic texts and interpretations quoted to support his views. He stipulates three developments that are necessary before redemption can take place. First, people must increase their observance of the commandments, which he interpreted as giving ones heart to return to Eretz Israel, the place of Torah. For support, he quotes Leviticus 25:38: to give you the land of Canaan in order to be your God.

Next page