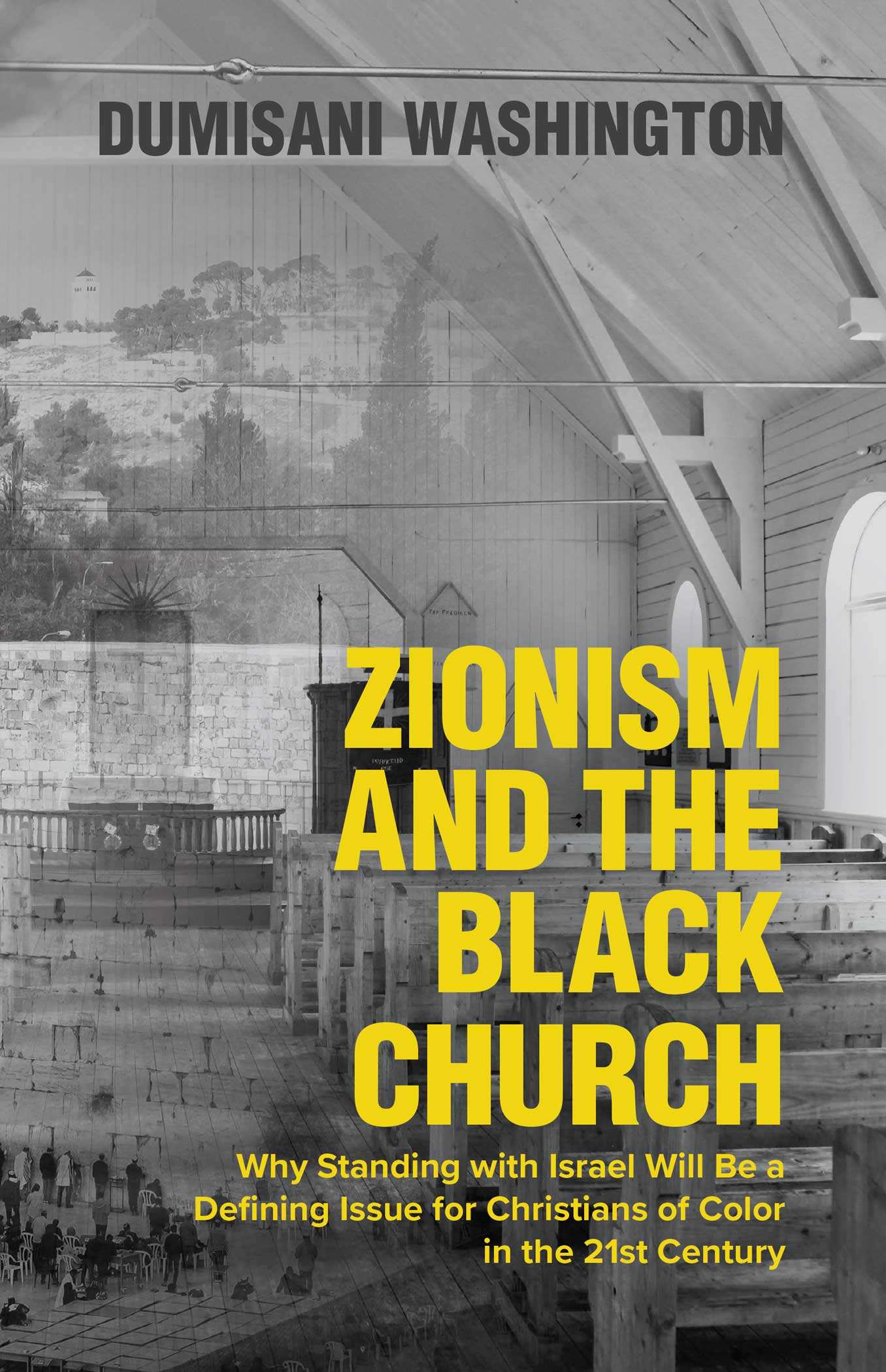

Published by

Umndeni Press

Charlotte, North Carolina

2021 by Dumisani Washington. All rights reserved.

Originally published by Institute for Black Solidarity with Israel (IBSI), 2014

ISBN (978-0-578-24569-0)

To the remnant

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank my wife of 32 years, mother of our six children, for her unwavering support since we were teenagers. I also wish to thank the Congregation of Zion in Stockton, California. Finally, special thanks to Melva L. Henderson, Wendy Cruz, Leah Washington, Gerri Pinkston, and Yasha Washington for your tireless help in making this second edition a reality.

INTRODUCTION

There is one universal Church. The Body of Christ is not Black or White. It is one Body. This book is not an effort to further divide Christians by race or ethnicity. The term Black Church in the title does not refer exclusively to a specific group of Christians, be they Baptist, Church of God in Christ, African Methodist Episcopal (AME), Hebrew Roots, Messianic any other denomination. From the birth of the Church at Pentecost in First Century Jerusalem, there have been multiethnic congregations. Black Church symbolizes Black Christians or other Christians of color, whatever their theological leaning may be. Also, Christian Zionism is a discussion that is paramount for all Christians regardless of ethnicity and for our Jewish brothers and sisters who may want to know more.

Zionism and the Black Church attempts to speak to the cause of Israel and the Jewish people to a community purposefully targeted with an anti-Zionist message. Once the lowest caste of any people in the Western world, chattel slavery, Black Americans generally have a sought-after perspective on issues of humanity. This is especially true of the Black Church. The Black, legendary struggle for justice has historically given the Black Church an air of validity and authority. Though a smaller portion of the U.S. population, Black people have influenced everything from music and art to theology, politics, education, and, of course, civil rights.

I started the Institute for Black Solidarity with Israel (IBSI) in July 2013, responding to what I can only explain as a divine call. In September 2014, I became the Diversity Outreach Coordinator for the now nearly ten million member Christians United for Israel (CUFI). My son, Joshua, currently serves as IBSIs Director. By profession, I am a musician, a piano performance graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. I am a pastor, a husband of 32 years, and a father of six extraordinary children, just like their mother. I am also a Christian Zionist, meaning I believe the Jews are Gods chosen people, and the land of Israel belongs to them. But, Israels right to live in peace goes well-beyond scriptural interpretation. When I advocate for the Jewish State outside of religious circles, I rarely quote the Bible. However, this book is a combination of history, politics, and preaching. There will be scriptures quoted in both English and Hebrew.

I was born Dennis Ray Washington on February 17, 1967, in Little Rock, Arkansas, the segregated South. I am the youngest of seven children. We moved to California when I was about one, so I have no early memories of Arkansas. I legally changed my first name to Dumisani in the early 1990s to embrace my African heritage. Dumisani means praise from the Zulu phrase dumisaniuYehovah (praise the Lord). My dear friend and sister Nomathemba Sithole, a South African national of the Zulu tribe, helped me choose my new name. Nomathemba is affectionately known to our family as Malume - Aunty.

My parents, David and Lillian Washington, were both from the Little Rock area born in the early 1940s and were part of a vibrant Black community. My mother was a seamstress from a young age. My fathers father was a sharecropper, so my father grew up on a large farm complete with cows, chickens, pigs, horses, cats, and dogs. They grew all sorts of crops, including cotton. My father did not graduate from high school in large part because he had to run the entire farm by himself when both his brother and father fell ill.

My mother often spoke about Little Rock and the life of the community she loved. We were active members of King Solomon Baptist Church, where Reverend Thomas was the pastor. As my mother told me, I loved music so much as a baby that I would rock and sway as the choir sang. Unfortunately for Reverend Thomas, I was not fond of preaching. I would cry at the top of my lungs whenever he took the podium. My mother had to take me out of the sanctuary virtually every week after the music ended. Perhaps I just wanted the music to continue. Either way, Mama said I gave our pastor a complex. She was not joking.

My father was a gifted singer, a leader of the mens chorus, and served on the deacon board. My mother was a deaconess and worked with the youth ministry, among many other things. She graduated from the only high school for Black children in Arkansas, Scipio Africanus Jones High School in Little Rock. S. A. Jones High School was the pride of Arkansas. Like many Black schools during segregation, there was a deep sense of connectedness among the teachers, administrators, and students. Throughout the history of Black people in America, education was the primary means of freedom and upward mobility. Black students from S. A. Jones graduated and went on to become doctors, lawyers, politicians, athletes, clergy... anything they aspired to be. My uncle, Dr. Levi Adams class of 51, had a long and illustrious career with the medical school administration at Brown University in Rhode Island. There is an award at Brown that bears my uncles name.12

Though I never directly experienced it, hearing my parents describe life in North Little Rock gave me a great sense of pride as well. I learned of the Little RockNine3 from my parents, who knew the families involved. I learned of the internal debate over integration. Many Black people knew that it would mean the end of their beloved S. A. Jones and other Black institutions in Little Rock. S. A. Jones closed in 1970 because of integration. The teachers and administrators were released and not allowed to work in the now integrated schools. For this reason and many others, my mother explained to me at a very young age; she was vehemently against forced integration.

My parents did not teach us hatred and contempt for White people. They taught us what racism was so that we would be prepared to face it. They taught us not to ascribe virtue or wickedness to someone simply based on their ethnicity. Ones character was who one was, not ones race. They also taught us to speak our minds and not be afraid of anyones disapproval, a lesson they demonstrated as much as they articulated. It was always in their blood. One of the most vivid stories my father told me was when he was about ten years old. The White landowner had come to the farm to check on my grandfathers work. As my father and grandfather were busy in the field, the landowner pulled up in his pickup truck and began berating my grandfather. My grandfather stood silently, avoiding eye contact as the man disrespected him in front of his young son. After a few moments, my father had all he could take. He abruptly climbed up the drivers side door of the pickup, got directly in the White mans face, and said, Hey, mister! I dont like the way you talkin to my daddy! At ten years old, my father did not fully understand that what he had just done could have gotten both he and his father killed. My grandfather gently removed my father from the mans truck, saying, Junior, get down.