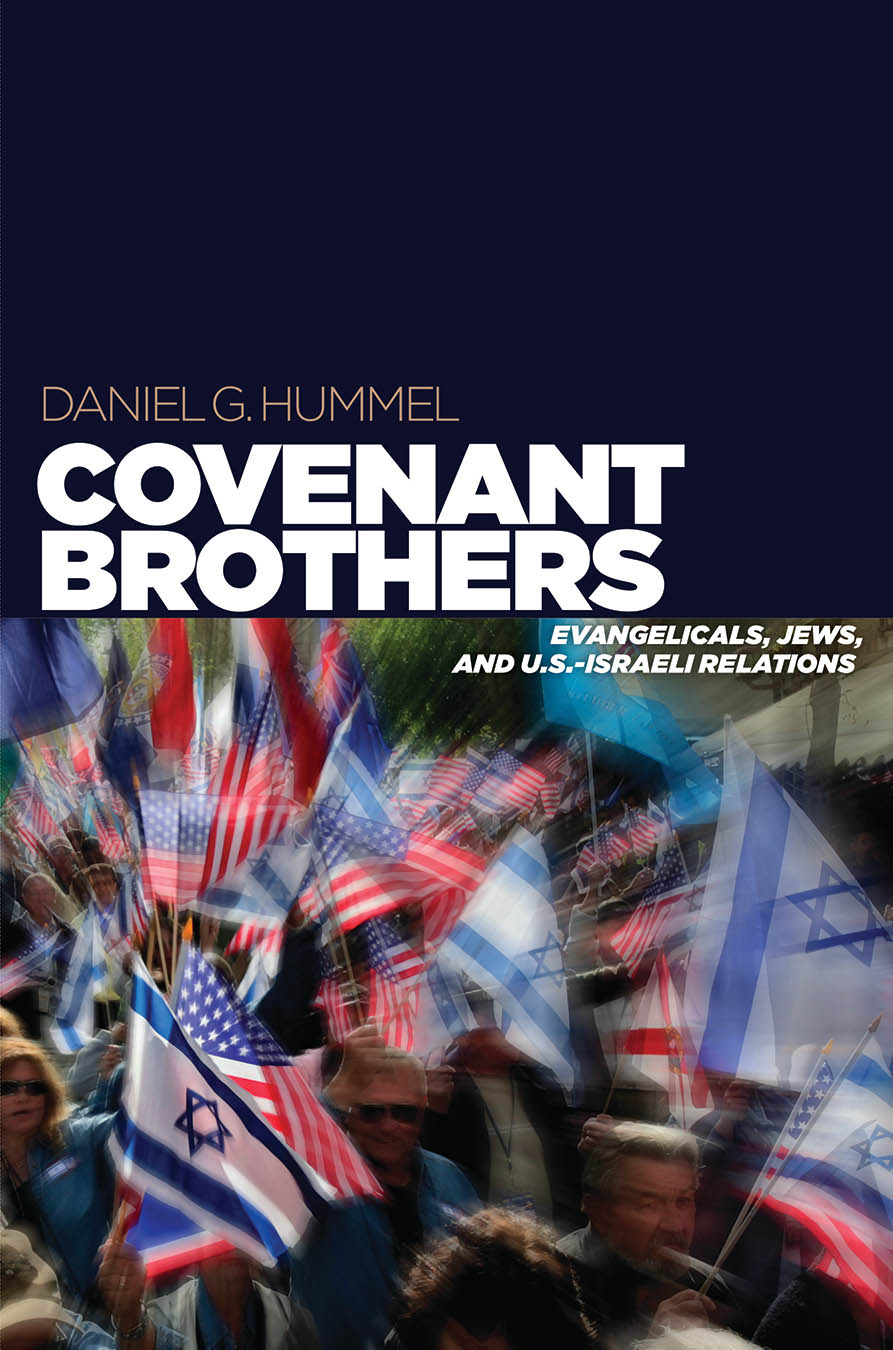

Covenant Brothers

COVENANT

BROTHERS

Evangelicals, Jews, and U.S.-Israeli Relations

Daniel G. Hummel

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-8122-5140-1

CONTENTS

ON THE SUNNY AFTERNOON of March 18, 1960, at the single checkpoint connecting the two halves of the city of Jerusalem, the worlds most famous Christian evangelist entered the state of Israel for the first time. Passing over the Allenby Bridge, through Mandelbaum Gate and the no-mans land between Israel and Jordan, Billy Graham drew a barrage of flashbulbs in the opulent lobby of the King David Hotel.

The consummate evangelist, communicator of the gospel to millions, pledged that he would not evangelize while in Israel. During his three-day visit, Graham restated his innocence, hoping to placate the Israeli government which had prepared for violent anti-Christian protests.

Grahams 1960 trip is one episode in the vast annals of evangelical encounters with Israel since 1948. Though rarely retold by historians, it sets the stage for a new understanding of the origins of the evangelical Christian Zionist movement, the organized political and religious effort by conservative Protestants to support the state of Israel.

For the reporters swarming Graham, and those who now cover Christian Zionism, two explanations of the curious evangelical fascination with the state of Israel have predominated, each grounded in supposedly fixed evangelical attitudes toward the Jewish people. In 1960, Graham roused suspicion that he wanted to convert Jews; since then, observers have focused on the evangelical desire to hasten the End Times. The apparent anticipation, even gleenot to mention salesthat these scenarios generate have disturbed and fascinated observers for decades.

Lindsey the doomsayer and Graham the evangelist represent the common archetypes of Christian Zionist motivations. Likewise, it has reduced Jews to little more than practitioners of realpolitik. Instead, Covenant Brothers posits that the evangelical political movement to support Israel is a product of advocacy, organizing, and cooperation beginning after the founding of the state of Israel in 1948 and advancing significantly in the wake of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. The recency of organized Christian Zionism suggests that it is not an obvious consequence of evangelical theology, nor is cooperation between evangelicals and Jews a natural political arrangement.

Reconstructing the rise of Christian Zionism as a movement fixes attention on the sea change in the ways most evangelicalsand certainly most

Observers of Christian Zionism have frequently emphasized the longstanding incompatibility of evangelical Christians and Jews, each understood as bounded groups with conflicting loyalties, beliefs, and values.

For the political organizers of Christian Zionism, theology and politics fused in new and unexpected ways after 1948. In its most activist circles today, Christian Zionism is less about apocalyptic theology or evangelism than it is a range of political, historical, and theological arguments in favor of the state of Israel based on mutual and covenantal solidarity. In recent years, a type of nation-based prosperity theology, promising material blessings to those who bless Israel, has played a prominent role. In earlier decades, atonement for Christian anti-Judaism and Israels strategic importance in the Cold War proved decisive. By turning attention to the origins of evangelical calls for religious and political activism, and to the institutions that now make up the movement, the scope and importance of Christian Zionism come into better focus.

Indeed, Grahams 1960 utterances in Israel studiously avoided both evangelistic and apocalyptic references. His admiration for Jesus as a Jew But it was out of postwar evangelicalism that there emerged a theologically oriented interreligious movement promoting social and political action on an international scale, binding evangelicals, American Jews, and the state of Israel into a closemany claimed, covenantalpartnership.

Reconciliation

If the prevalent understanding of evangelical Christian Zionism has attributed the movement to ulterior evangelistic and apocalyptic motives, a far different interpretation has predominated among Christian Zionists. Seeking to sanction and, in many cases, paper over the theological and historical incommensurability of evangelical Christian and Jewish cooperation, insiders of the movement have emphasized the Judeo-Christian essence of Zionism. Some have invoked Protestant Reformers and church fathers as historical precedents, while others have celebrated the exceptional history of Western civilization and the natural affinity between the United States and Israel. This reading of the movement fails on multiple levels to grapple with the unacknowledged conciliations, sleights of hand, and partial histories that have driven evangelicals and Jews together. The movements own histories have so far failed to provide critical distance from Israeli state interests or acknowledge the rapid changes in theology it has brought about.

These histories, along with the slew of new scholarly research, do reveal that at the institutional level, the evangelical Christian Zionist movement is built on three pillars of recent origin: interreligious encounter, support by the government of Israel and by American Jewish allies, and changing evangelical attitudes toward political mobilization. Together, these pillars go a The verse outlines the covenantal language (reaffirmed in Genesis 15 and forward) that is the basis for modern Jewish-evangelical political cooperation. From informing the names of organizations, to the language of interreligious dialogue, to the substance of political arguments, Genesis 12:3 is the organizing principle of the modern Christian Zionist movement.

Genesis 12:3 shapes how Christian Zionists understand their relationship not only to Israel but also to the rest of the Bible. Romans 911, part of the letter written by the apostle Paul to the church in Rome, is perhaps the most cited passage in modern Jewish-Christian dialogue. Christian Zionists interpret the passage in light of Gods declarations in Genesis. In Romans 11, Paul uses roots, olive shoots, and branches to describe the relationship between Jews and Christians. If some of the branches have been broken off, and you, though a wild olive shoot, have been grafted in among the others and now share in the nourishing sap from the olive root, Paul writes to his Christian audience, do not consider yourself to be superior to those other branches. If you do, consider this: You do not support the root, but the root supports you (Romans 11:1718). The implications of Pauls writings are clear to Christian Zionists: the two faithsthe two covenanted peoples of Israel and the churchhave a shared root, a shared faith, a shared fate.

Thus Christian Zionism is conceived of by evangelicals as a joint Jewish-Christian project. Indeed, at each stage of its development, the Christian Zionist movement has been shaped by the strategic interventions of Jews, in both Israel and the United States. The cast of characters is large, from Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, longtime director of interreligious affairs at the American Jewish Committee, to Israeli officials staffing the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to prime ministers and other cabinet officials. In more recent years, Orthodox rabbis, including Yechiel Eckstein, founder of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, and Shlomo Riskin, rabbi in the West Bank settlement of Efrat, have forged deep ties with Christian Zionists and expounded upon a shared covenantal theology. Taken together, these Jewish allies of Christian Zionism have convinced a segment of evangelicalism to revise and reform its attitudes and beliefs about the relationship between Judaism and Christianity.