The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Peter Booth Wiley Endowment Fund in History.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2021 by Mitchell Schwarzer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schwarzer, Mitchell, author.

Title: Hella town : Oaklands history of development and disruption / Mitchell Schwarzer.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020054657 (print) | LCCN 2020054658 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520381124 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520381131 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: City planningSocial aspectsCaliforniaOakland. | City planningPolitical aspectsCaliforniaOakland. | Oakland (Calif.)HistoryPolitical aspects. | Oakland (Calif.)HistorySocial aspects.

Classification: LCC F869.O2 S38 2021 (print) | LCC F869.O2 (ebook) | DDC 979.4/66dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054657

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054658

Manufactured in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

There is no there there, Gertrude Steins notorious statement about Oakland, appeared in her 1937 memoir, Everybodys Autobiography . Stein lived in Oakland from age 6 to 17. In 1891, she moved with her family to Baltimore, and in 1935, now a noted author and socialite, returned for a lecture tour. Speaking at the English club at Mills College, she grudgingly agreed to visit her former stomping grounds around 13th Avenue and E. 25th Street. In the intervening 44 years, the landscape had been recast from an occasional farmhouse, surrounded by rose bushes and peach and eucalyptus trees, to corridors of single-family dwellings. The Steins family house and expansive grounds were gone. Gertrude was disoriented and later penned the famous remark. Regardless of the fact that she was expressing the kind of disappointment that most people would feel upon revisiting a home long departed and witnessing that everything had changed, her words have since underpinned a false impression that Oakland is lacking in something, in someplace.

It is worth recalling that in 1935 what may have distressed Stein had uplifted the builders of the district as well as its residents and businesses. Starting in the 1890s, Oaklanders experienced a profound increase in their personal mobility through the aegis of electric streetcars, which turned the walking city into a radial metropolis. After the 1906 Earthquake, which destroyed San Francisco, Oaklands growth accelerated. New industries capitalized on Californias growth. Housing construction ramped up, and macadamized roads were laid for the latest mass phenomenonautomobiles. At the time of Steins visit, the Great Depression had dampened investment, but it resumed with a vengeance during the Second World War.

Figure 1. Steins old neighborhood. In the vicinity of 13th Avenue and E. 25th Street. Photo by Mitchell Schwarzer, 2020.

Had Stein been able to come back 44 years after her lecture tour visit, in 1979, she would have experienced a city transformed once more. Scattered apartment buildings broke up single-family house rows, many of whose windows were now secured by metal bars. Buses ran where streetcars had. Upslope, an eight-lane freeway coursed across the base of the hills, and higher still, on what had been cascading carpets of wildflowers, the latest subdivisions were being erected. Down by the waterfront, the manufacturing belt was emptying. Once-vibrant commercial arteries were marred by unoccupied storefronts and vacant lots. Another process of city change was taking place: disinvestment yielding deterioration.

When Stein visited her former neighborhood, she had recently returned to America after having spent over 30 years in Paris. Approaching a city like Oakland with European preconceptions of stability, hierarchy, and monumentality invariably leads to disappointment. Place in California is better understood as a verb and not a noun, a process of moving and making and remaking. If Oakland appears faceless at times, that is less a flaw on its part and more an inability of an observer to appreciate the fits and starts of urbanization in a California city. Instead of a grand canvas showing finished pieces in flawless order, cities like Oakland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, and even the European-seeming San Francisco expose snapshots of city formation and deformation, driven by economics, technology, and politics: one where the Civil War jump-started cotton production in California farmlands, leading to cotton manufacturing alongside the waterfront; another where an innovation in transportation, the electric traction streetcar, cast commercial strips across the flatlands and lower hills; and another still where the racist approach to guaranteeing mortgage loans on the part of a federal agency, the Home Owners Loan Corporation, brought deprivation to minority neighborhoods.

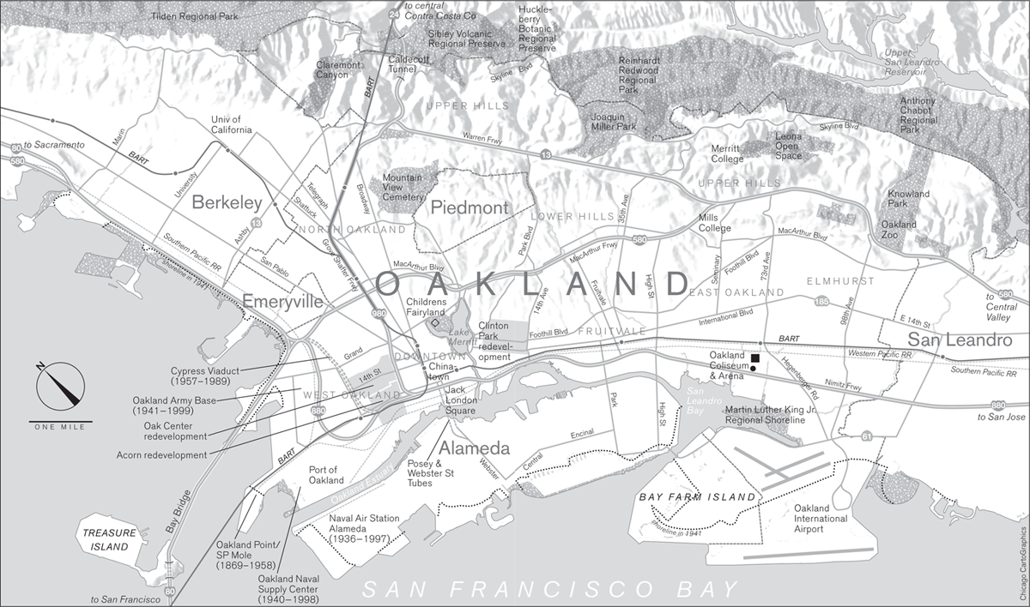

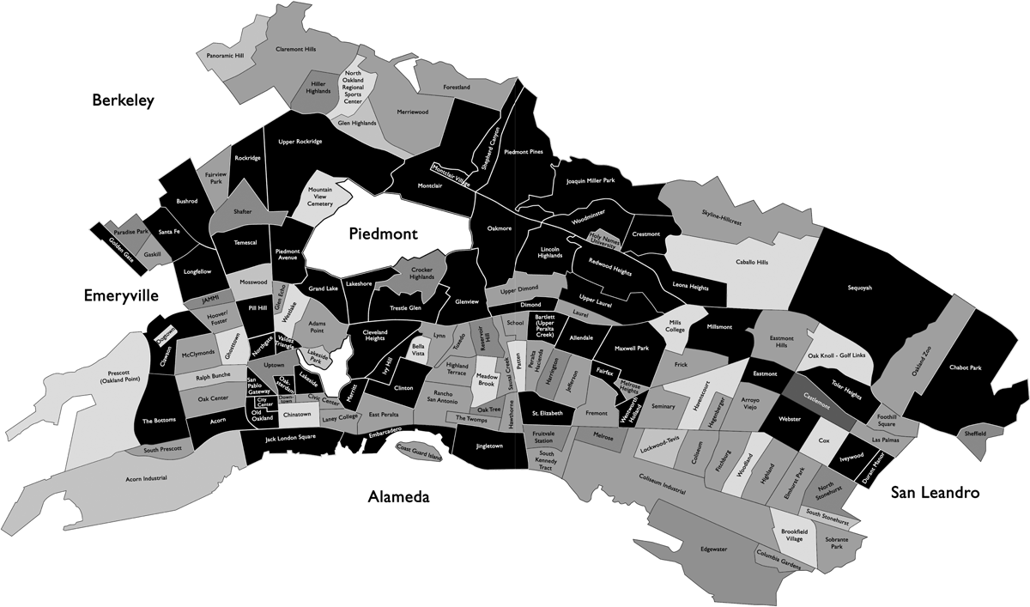

Land-use and building patterns are a puzzle that can only be deciphered by going back in time, following the patchy moments when plans get realized, or not, when the variable trajectories of real estate acts become apparent, and when the changing priorities of governmental and business entities make themselves felt. After progressing northward from the waterfront, Oakland coalesced a retail district on lower Washington Street and an office center around 14th and Broadway. While a new office district arose along Lake Merritts western end, the retail district continued to move north along Broadway, and then disintegrated. Numerous plans were hatched for a civic center on the lakes southern side; Oakland ended up with three dispersed collections of governmental buildings, and only one by the lake. When land was available, Oakland leaders failed to set aside a large central park in the vicinity of Lake Merritt. Park acquisitions took place primarily in the upper hills, far from where most of the population lived.

It is from those lofty heights where we can get a comprehensive visual picture of Oaklands land-use and building patterns: the waters claimed from the bay for manufacturing and the Port of Oakland; the transportation-industrial corridors paralleling the waterfront; the high-rise offices and residences downtown and by the lake; the sea of low-rise housing stretching from those districts across the flatlands, lower hills, and upper hills, punctuated here and there by hospitals, church spires, and a tall office or apartment block. Equally, we can construe the citys natural geography: a sweep of terrain fronting an estuary of San Francisco Bay and shielded by the San Francisco peninsula from the direct winds and fog of the Pacific Ocean; a landscape canvas ascending from the bays salt marshes to alluvial plains to undulating hillsides and finally steep canyons and peaks topping out at 1,760 feet.