The First Age of Industrial Globalization

NEW APPROACHES TO INTERNATIONAL HISTORY

Series editor: Thomas Zeiler, Professor of American Diplomatic History, University of Colorado Boulder, USA

New Approaches to International History covers international history during the modern period and across the globe. The series incorporates new developments in the field, such as the cultural turn and transnationalism, as well as the classical high politics of state-centric policymaking and diplomatic relations. Written with upper level undergraduate and postgraduate students in mind, texts in the series provide an accessible overview of international, global and transnational issues, events and actors.

Published

Decolonization and the Cold War, Leslie James and Elisabeth Leake (2015)

Cold War Summits, Chris Tudda (2015)

The United Nations in International History, Amy Sayward (2017)

Latin American Nationalism, James F. Siekmeier (2017)

The History of United States Cultural Diplomacy, Michael L. Krenn (2017)

International Cooperation in the Early Twentieth Century, Daniel Gorman (2017)

Women and Gender in International History, Karen Garner (2018)

The Environment and International History, Scott Kaufman (2018)

International Development , Corrina Unger (2018)

Forthcoming

Canada and the World since 1867, Asa McKercher

An International History of Modern Colonial Labour: Debates and Case Studies , Miguel Bandeira Jernimo and Jos Pedro Monteiro

The International LGBT Rights Movement , Laura Belmonte

Reconstructing the Postwar World , Francine McKenzie

Scandinavia and the Great Powers , Michael Jonas

The First Age of Industrial Globalization

An International History 18151918

MAARTJE ABBENHUIS AND GORDON MORRELL

Who but a lunatic would try to bring the endless information about contemporary life into a single focus? Theodore H. von Laue (1987)

Contents

This book is the product of many years of daily conversation and not a few heated debates (over coffee, while doing the dishes, going grocery shopping and cooking dinner) about what constitutes nineteenth-century globalization and why that globalization is historically relevant. Mostly, it is a book that aims to explain the seeming oxymoron that the world became a more global place during the nineteenth century and that the rising sense of global connectiveness mattered in fundamental ways to contemporaries and to the nineteenth-century international environment. It is a book written for our students, who continue to grapple with some essential questions relating to the global impact of the industrial revolution, capitalist imperialism and the evolution of the modern world.

Books like these are never finished, they are artefacts of a particular moment, and they speak to the many influences in their authors lives as academics, historians and teachers and, in our case, as partners in all walks of life. We are grateful to the many inspirational historians who came before us, who framed the nineteenth century as a globally integrated space and who carved out ways of interpreting and understanding the nineteenth-century world as one of immense and intense change. Without them, this book would not exist. We walk in the footsteps of giants, stumbling all the way.

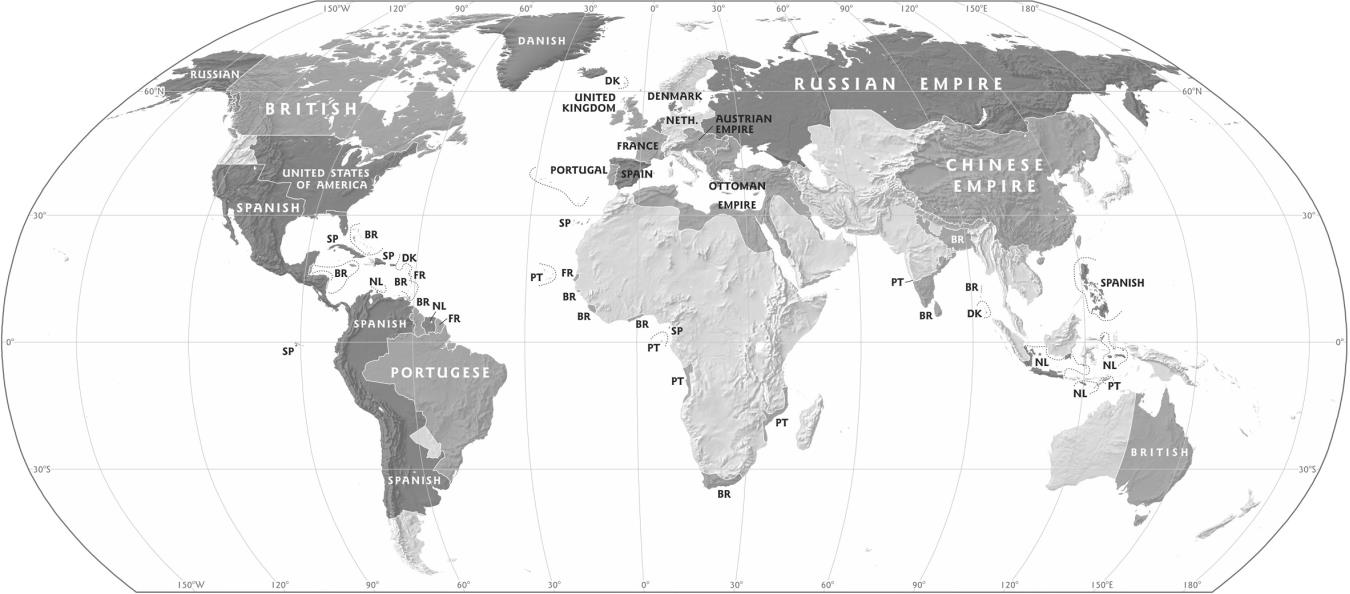

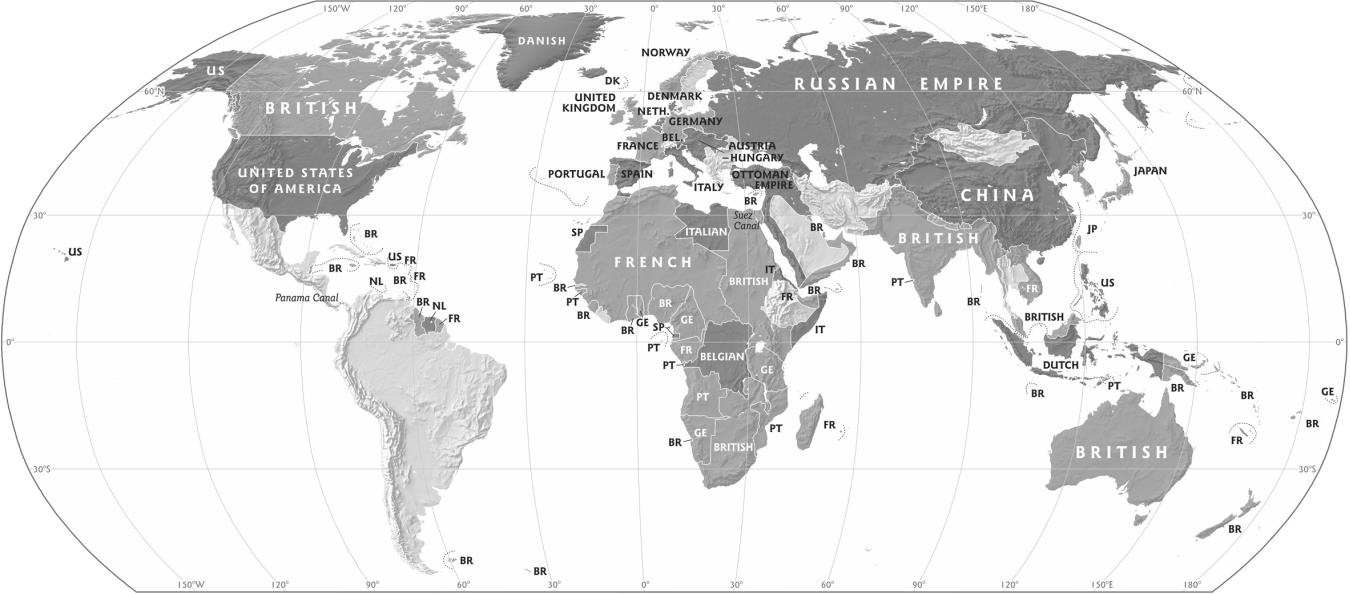

Alongside these historians and our students at the University of Auckland and Nipissing University (Ontario), we would also like to take this opportunity to thank some key individuals who enabled this project to take form as it did, including: Sam Jaffe for his bibliographic work; Hazel Petrie, Preeti Chopra, Genevieve de Pont, Annalise Higgins, Sara Buttsworth, Matthew Hoye, Remco Raben and Angelie Sens for their feedback and reading suggestions; Igor Drecki for the maps; and the School of Humanities at the University of Auckland and Bloomsbury Publishing for their financial and material support.

We wrote this book for our students, aiming to offer an accessible international history of the nineteenth century as an age of globalization. Each chapter presents an argument on a particular theme relating to the impact of the industrial revolution as it went global after 1815. It is a book of synthesis, integrating several existing approaches to the history of nineteenth-century globalization, industrialization, warfare, diplomacy and imperialism. We have kept our references to a minimum, focusing on the most useful or accessible sources when possible. Each chapter finishes with a series of study questions, which may be useful to instructors and students alike. We also conclude each chapter with a list of recommended readings, mostly chapters and journal articles that we found particularly lucid, illuminating or interrogative. We hope that they supplement readers understanding of the text and lead them in interesting and exciting directions.

Source: Igor Drecki (designer), 2018.

Source: Igor Drecki (designer), 2018.

It is a truism to state that two hundred years ago the world was quite a different place than it is today. But it really was. In 1815, where we begin our history, wherever you looked in the world, most people lived in agricultural societies supported by the produce that came off the land or out of the sea. As they had for centuries, their daily lives were influenced by seasonal calendars: by the needs of planting, growing, harvesting, or of fishing, hunting, gathering. Even if they lived in a city (as about 3 percent of them did), their livelihoods were locally or regionally focused. Their social customs, mores and religious practices were influenced by the community in which they resided and the political authority that was in charge (be it an empire, kingdom, tribe or republic). Power was generally wielded by a small caste of elites, whose lives and livelihoods tended to be served by the rest. For most, the pace of change was slow and measured. Barring extraordinary events such as those occasioned by wars, invasions, regime changes, famines, plagues and natural disasters peoples lives were relatively predictable, if often precarious. In one lifetime, most would not travel further than a few miles from the place where they were born.

There were, of course, exceptions. Merchants, traders, sealers, whalers, bankers, entrepreneurs, bureaucrats, diplomats, adventurers, colonizers, missionaries, soldiers, labourers (both free and unfree) and those seeking a new life crossed the oceans and continents, exchanging luxury goods, precious metals, new inventions, new knowledge, plants, pathogens and diseases as they moved themselves and other people, at times against their will. Long-distance travel was slow, costly, weather-dependent and often dangerous. For example, a journey from London to New York could take three or four weeks, sometimes longer; from London to India around six months. News, information and letters travelled equally slowly: by foot, horseback or camel on land, by sail at sea.