This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2020 by Eunice Blavascunas

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-04958-2 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04960-5 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04959-9 (ebook)

12345252423222120

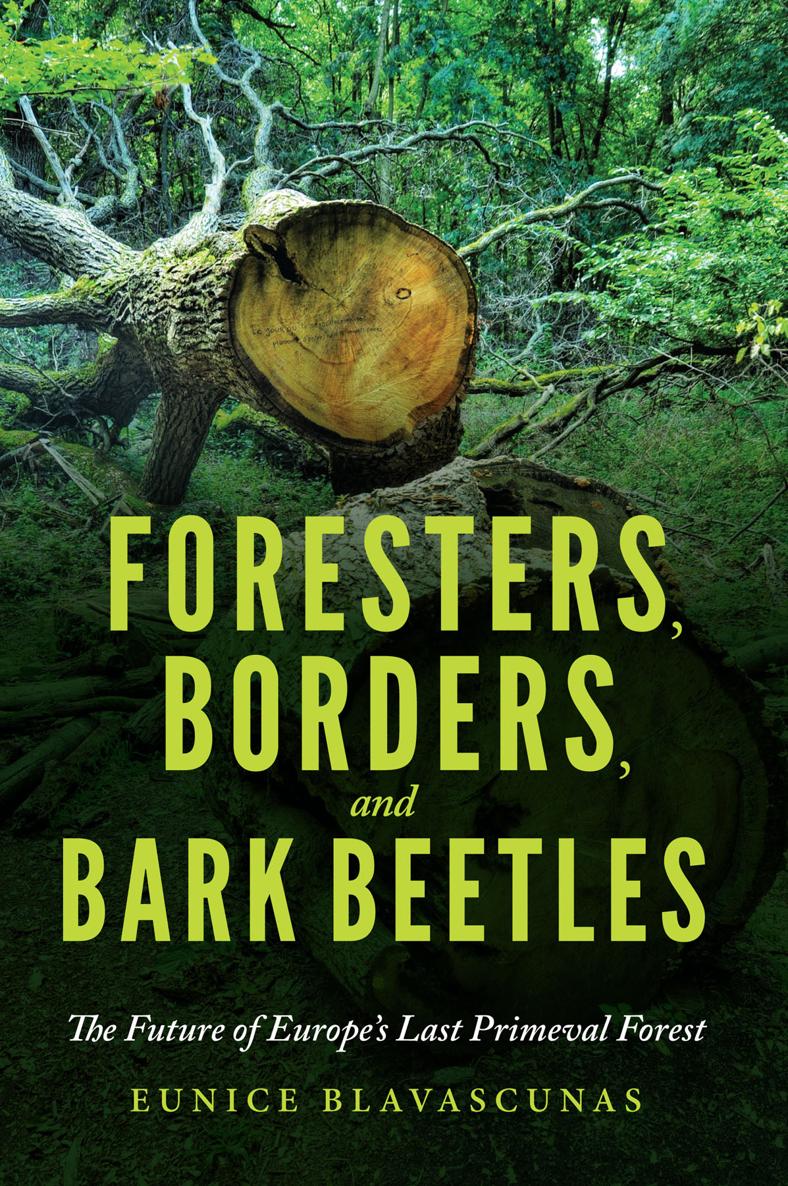

T HE FOREST, NAMED AS YOU ARE, B IAOWIEA, OF tree, moss, mushroom, animal, humanfor twenty-four years, you have been the humus from which this book emerged. I know you because of the time I have spent under your canopy and at your edges. I know you because of the stories people have told me about you and because I have read about you. I know you from multifold actions and conversations that flow around you. Through history and lived experience, I acknowledge you.

Writing this ethnography after decades of research raises the fundamental question of what belongs to whom. As much as I secluded myself to write this book and painstakingly crafted its sentences, paragraphs, and chapters, I do not believe that I am an atomized, individuated subject who has solely produced the story. Like the forest, this writing has existed in relation. It is here that I acknowledge how others contributed, whether they fed me a steady diet of encouragement or served up platters of critique. A book is produced through a series of negotiations and tensions that the author learns to navigate. I thank the people and institutions named here for their medicine, mud, recipes, suggestions, edits, personal stories, assistance, political positions, and science.

This book traveled far from my doctoral thesis, yet I would like to acknowledge my teachers and mentors at the University of California Santa Cruz. The contours of their knowledge projects shaped who I am as a thinker and writer. Ravi Rajan, my doctoral advisor and friend, you invite difference and treat it hospitably. Your pioneering work on the history of forestry and colonial sciences influenced this books longue dure coverage of the sciences. I hope that I have followed your sage advice and just told a good story.

Melissa Caldwell contributed rigor and compassion, continually working to strengthen my ideas by pushing me to always reach just beyond my intellectual limits. Donald Brenneis helped me defend the value of a now rare long-term ethnographic engagement. Carolyn Martin Shaw and Dan Linger taught me how to successfully write applications for the many grants that funded this project. Anna Tsing taught me the art of noticing and how to ethnographically explore entanglements between humans and nonhumans. Donna Haraway deserves credit for helping me use different intellectual senses than I was used to. To all my graduate student colleagues, with whom I grew, you opened oysters full of wisdom: Conal Ho, Riet Delsing, Jessica OReilly, Kristine Baker, Bettina Stoetzer, Alisa Puga Kessey, Kristen Cheney, Scout Calvert, Harlan Weaver, Eben Kirksey, Jeremy Campbell, Noah Tamarkin, Meghan Moodie, Jake Metcalf, and Heath Cabot. While exploring the forest through the lens of geography at the University of Texas at Austin, Robin Doughty, along with Bill Doolittle and Karl Butzer, encouraged me to trust my intellectual creativity and always remember small acts of kindness.

The writing of this book began in earnest through a generous fellowship at the Rachel Carson Center in Munich, Germany. Thank you Christof Mauch and Helmuth Trischler for crafting a creative space for scholars. My colleagues at the center read and commented on multiple early chapters; my thanks to Nicole Seymour, Ruth Oldenzieil, Seth Peabody, Donald Worster, Jenny Price, Celia Lowe, Ursula Muenster, and Shen Hou. Thank you also to Markus Krzoska, Thomas Bohn, and Aliaksandr Dalhouski at the University of Giessen for your own book on Biaowiea and for including me in your formative historical workshops on your coverage of the topic.

I finished writing this book at the Leibniz Institute for East European History and Culture. Dietlind Hckter facilitated this opportunity and pushed me to think in new ways about Poland and materiality. Frank Hadler enabled me to make global linkages I would not have otherwise made. Christine Goelz deserves a special mention for background support. In Leipzig, Tracey Wilson shared ideas about Polish scholarship on the environment. Marc Allen Herbst animated thinking about antifascist organizing when it comes to all things environmentally related.

Indiana University Press series editor Jennika Baines deserves credit for her judicious and gracious go-betweens. Two anonymous reviewers also made careful efforts to help me see the holes in the manuscript and fill them with substance.

I would not have reached this forest had it not been for the US Forest Service, its Pacific Northwest Research Station, and Dr. Steve Berwick. He was kind enough to share his contacts and library with me before my first visit in 1995, and this proved indispensable in terms of who I would have access to and how. Simona Kossak generously introduced me to Biaowiea. She and Polish State Forests Forest Research Institute ensured that I was housed and hosted. They endured my evolving questions and fulfilled some of my basic needs, as did Ella Kudlewska; her mother and father, Wiesawa and Stanisaw; her daughter Karolina, who assisted me with translations; her sister Gosia Kudlewska, who often cut my hair; and her brother Adam, who let me accompany him and Dr. Elbieta Mahlzahn to distant forest hamlets. Thank you to Magosia Buszko, Lars Briggs, Lars Christian, and Olimpia Pabian for including me in your 1995 amphibian workshops, which brought laughter, meetings with farmers, and knowledge of what it means to sleep with the mosquitoes. Thank you, Monika Kurzawa, for traveling by my side in after that workshop and teaching me about Polish history. Krzystof and Joanna Zamojski kindly opened their house, making holidays more bearable. Jadwiga and Staszek Sawrycki fed me many pierogi stuffed with garden cabbage and forest mushrooms and shared their love of bees on many a cold winter night. Andrzej Bobiec took my project and young ideas very seriously. I am deeply indebted for the amount of time and energy he gave me. Andrzej Antczak facilitated many introductions and always ensured that I would hear multiple types of stories in the forest region. Kazi Borowski provided tech support when the internet was pretty new in Biaowiea. Thank you to Joanna Kossak for needed translations and teaching me that difficult circumstances can lead to joy.

The scientists and staff at the Polish Academy of Sciences Mammal Research Institute were extremely gracious. They let me follow them on radiotelemetry outings; talk with them while they collected bat, bison, and weasel data; and generally spend time with them in their lunchroom and homes. Thank you to Jan Wojcik, Rafal Kowalczyk, Ireneusz Ruczyski, Krzysztof Schmidt, Karol Zub, Krzysztof Niedziakowski, Paulina Szafranska, Bogumia Jdrzejewska, and Tomasz Borowik for maps and conversation and to Tomasz Samojlik, who explained Biaowieas history in his