This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2018 by Valdimar Tr. Hafstein

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-03792-3 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-03793-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-03794-7 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 23 22 21 20 19 18

FOR ME, IT didnt start with heritage. I came to the study of folklore through mythology. At the age of nineteen, I signed up for a class in Norse myths at the University of Iceland. It was one of the courses taught toward the major in folklore; in the following semester, I took three more. The die was cast. In the following semesters, I studied customs and rites, tales and legends, material culture: the bread and butter of folklore programs in the twentieth century. My interest in myths soon subsided for more pedestrian subjects, like everyday life and the way people give it meaning. Interpretation of texts made way for fieldwork. My parents shrugged, patiently waiting for me to get serious. My father only brought it up once, gently suggesting that whatever I chose to do, I should make sure I could provide for a family. My father had gone to law school, but during finals in his last year he was offered a job at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He had his doubts, but my mother wanted to see the world. Within a month of his last exam, they moved with their firstborn to Stockholm. At twenty-six, my father was abroad for the first timean accidental diplomat.

Growing up, I moved with my family to Brussels and Geneva, Europes diplomatic capitals, EU and NATO headquarters in the former, the UN office, ILO, WHO, WIPO, and a host of other acronyms in the latter. My father moved up through the ranks. He became ambassador and Icelands chief negotiator in a number of intergovernmental agreements, treaties, and conventions. My mother raised four children in various cities and took on the many diplomatic tasks that came with my fathers position. They were both great at what they did.

It never occurred to me that I had followed in their footsteps. Honestly. Nor to them, I think. It only dawned on me in 2005. I was thirty-two. Thirteen years had passed since I took my first folklore course. This was shortly before my fathers death in August that year, a few months after I finished my PhD at Berkeley. By then I had already been going to UNESCO and WIPO meetings for three years as a participant observer. At UNESCO, I was part of the Icelandic delegation, sitting in alphabetical order among other state delegates, most of them lawyers. At WIPO, I sat on the back benches as an observer representing either SIEF (International Society for Ethnology and Folklore) or AFS (American Folklore Society) or both. I was on my way out of WIPOs headquarters, a thirteen-story tower encased in sapphire blue glass by Genevas Place des Nations. I had spent the week in the conference rooms and foyers following diplomatic debates on copyright and folklore. Crossing the marble floors of the lobby in my blue suit, briefcase in hand, it struck me: I had turned into my father. I was an accidental diplomat.

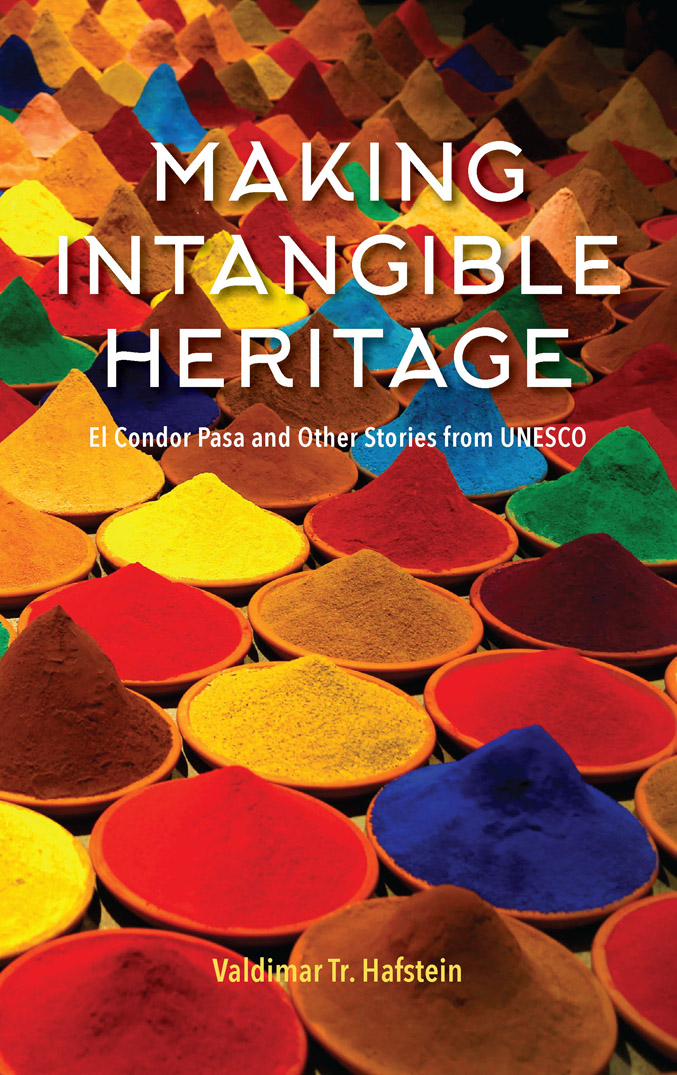

WHAT UNITES BEER culture in Belgium with Chinese shadow puppetry? What do Estonian smoke saunas have in common with kimchi making in the two Koreas or with summer solstice fire festivals in the Pyrenees? How about the Capoeira circle in Brazil and the gastronomic meal of the French? How is tightrope walking in Korea like violin craftsmanship in Cremona, Italy, and how are both of these like Indonesian batik, Croatian lacemaking, Arabic coffee, and Argentinian tango? What might connect yoga in India with the ritual dance of the royal drum in Burundi, carpet weaving in Iran, or Vanuatu sand drawings?

The answer: these cultural practices and expressions are all on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). That means they have been selected to represent the diversity of human creative powers. Chosen because they give aesthetic form to deeply held values, they speak of skill and competence, of bonds that tie, and of different relationships to history, society, and nature. They testify to various ways people tend to previous generations, to other people, and to the universe. UNESCOs Representative List displays humanity at its best, showcasing its capacity to create beauty, form, and meaning out of its various particular circumstances. Sharing what they enjoy or endure, people give form to value in their cultural practices and performances (see Hymes 1975). New generations recreate these forms according to their own conditions, cultivating the talent, the knowledge, and the necessary appreciation. It is this creative dynamic that member states of UNESCO have set out to safeguard. The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage makes us all responsible for the continued viability of these cultural practices and expressionsfor making sure that their practitioners can keep practicing them and that future generations can continue to be inspired by them.

The convention frames them in terms of cultural heritage, a concept into which UNESCO itself has breathed life over the past half century. This concept defines a particular relationship to the objects and expressions it describes, one that is of recent vintage. We tend to assume cultural heritage has been around forever; in fact, it is a modern coinage and its current ubiquity is limited to the last few decades (Klein 2006; Bendix 2000; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998; Lowenthal 1998; Hafstein 2012). Its novelty speaks of contemporary societies and to their own understanding of themselves, their past, present, and future (Holtorf 2012; Eriksen 2014). Valuing a building, a ritual, a monument, or a dance as cultural heritage is to reform how people relate to their practices and their built environment, and to infuse this relationship with sentiments like respect, pride, and responsibility. This reformation takes place through various social institutions that cultural heritage summons into being (centers, councils, associations, clubs, committees, commissions, juries, networks, and so on) and through the forms of display everywhere associated with cultural heritage: from the list to the festivalnot to omit the exhibition, the spectacle, the catalog, the website, or the book. Folklorist Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett refers to these as metacultural artifacts (1998, 2006): cultural expressions and practices (e.g., lists and festivals) that refer to other cultural expressions and practices (carpet weaving, ritual dance, tightrope walking) and give the latter new meanings (tied, for example, to community, diversity, humanity) and new functions (e.g., attracting tourists, orchestrating difference). A hallmark of heritage, following Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, is the problematic relationship of its objects to the instruments of their display (1998, 156). This book brings those problems into plain view. But of course, this book is itself a metacultural artifact, a critical addition to the profusion of publications, websites, newsletters, press releases, and exhibitions brought forth as a result of UNESCOs global success in promoting intangible heritage. The book goes back to the moments of inception, the making of the concept and of the convention dedicated to its safeguarding, and to its genealogyevents, actors, and circumstances that gave rise to intangible heritage.