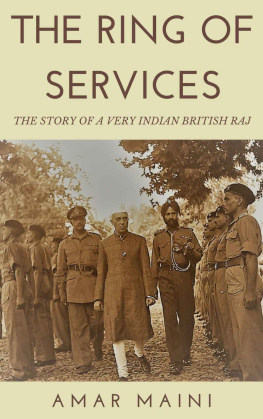

Amar Maini - The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj

Here you can read online Amar Maini - The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Amar Maini: author's other books

Who wrote The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE RING OF SERVICES

THE STORY OF

A VERY INDIAN BRITISH RAJ

Amar Maini

Cover Image: Prime Minister Nehru visiting the Srinagar Brigade Headquarters Military Hospital, May 1948. Courtesy of Public.Resource.Org

Introduction

W hen the Indian National Congress began its practice of non-cooperation after World War I it ran head on into the steel frame of the British Raj, the Indian Civil Service. As Mohandas Gandhi launched campaigns of satyagraha and civil disobedience against the Raj and began to challenge the centuries old relationships of co-operation between Indians and the British rulers, the Indian Civil Service had to step in and enforce the writ of the state. The elite bureaucracy engaged in constant intelligence work to undermine the Congress, attempted to stifle its growth with the help of Indian collaborators, and in the last resort directed the police and army in the violent repression of its political agitations. From 1920 until 1942 the Congress and the Indian Civil Service were thus in constant conflict at all levels of Indian society. During this period Congress rhetoric changed from pleas for the greater inclusion of Indians in the service, to threats to tear it down once Independence was achieved.

So when Independence came and an article guaranteeing the rights of those Indians who had served in the Indian Civil Service and Indian Police during the days of British rule was brought before the Constituent Assembly finalising the Indian Constitution on 10 October 1949, it was no surprise that many Congressmen objected. The most vocal among them thought it ludicrous that the Indian Civil Service, particularly its Indian officers, should be given any special privileges in the new order. Some of the Congress rank and file felt that the service should be wound up and replaced with something new. Rohini Chaudhuri reminded the chamber that Indians in the Indian Civil Service had never made any sacrifices for Independence, which meant that they should not enjoy any guarantees of remuneration under the new state. M. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar railed against any guarantees for the service, warning that those who had been rulers under the previous regime would continue to be so under the new one. He reminded the Assembly that Indians in the Indian Civil Service had committed excesses against the Congress thinking that this was not their country. Panjabrao Deshmukh joined the chorus, describing the Indian Civil Service as a remnant of the days of our slavery. Ramnarayan Singh remembered; we were maltreated, oppressed, and jailed by them.

Yet despite the condemnation of the Indian Civil Service and its Indian officers and the bitter memories which many Congressmen held of their time as political prisoners, guarantees were made for the old service in the new constitution and Indians in the service did continue and flourish under the new regime, largely as a result of Vallabhbhai Patel's intervention. Speaking as India's first home minister, he invoked the teachings of Gandhi to try to cool tempers and the desire for revenge. He pointed out that the Indians in the Indian Civil Service had served the previous regime ably, which was proof that they would do the same for the new regime; loyalty to the state was the essence of their job. Patel's speech on the floor of the Assembly stood against the tide of sentiments of his fellow Congressmen. He was a lone voice speaking for the continuity of the service at the core of the Indian state structure. His intervention may have seemed isolated, and even random. But like all seemingly random events Patel's speech that day in New Delhi was driven by history. In this case a historical process stretching back to the introduction of English education in India 150 years earlier, and the creation of a new and unique class of Indians which sought employment with the British Raj.

Indians had provided services to the British merchants of the East India Company from the time that they arrived in the country in the 17 th century. They worked as middlemen, accountants, lenders and interpreters and their skills were crucial for the development of British trade in India. Indian soldiers also fought for the Company's armies, and by the end of the 18 th century the British found themselves in possession of vast territories in the east, south and west of the subcontinent. It was in their effort to construct a government that they came to further rely on co-operation from Indians. A small group of Englishmen could not possibly staff every position in the government of such a huge land, and the cost of bringing Englishmen from England to fill every post would erode the balance sheets of what was still a commercial enterprise. Instead the Company bosses decided to promote a system of education which would instruct a small class of Indians in the English language. English education prepared Indians to staff the lower levels of government as clerks working under the supervision of British officers. The mundane work of processing paper would thus be speeded up, whilst the Englishmen would handle the more sensitive matters of state.

The numbers were small at first. In a population of over 100 million, English education only touched a few thousand Indians in the presidency capitals and centres of British administration. By the mid 19 th century Indian university graduates only numbered in the hundreds. But as the 19 th century progressed English education expanded much beyond what the British had planned for. Indians started to invest in English education for the prospect of government jobs and with higher education they were no longer content simply to remain clerks, they aspired to the higher positions of state such as those in the Indian Civil Service. These rising aspirations would hit a brick wall however. As a small group of Indians fully embraced English education and began to talk back to their colonial rulers, the British, at the height of their power, would claim that Indians could never be trusted with the senior positions of state on the grounds of race. The argument was made that no amount of book learning could bring an Indian up to the level of an Englishman; the two races were completely distinct and the old British officer-Indian clerk relationship which had built the Raj would remain in place.

Despite tensions between the Indian middle class and the British rulers that imperial relationship continued largely undisturbed until World War I. The Indian National Congress was formed in 1885 and the first and second generations of Congressmen remained resolutely moderate. Although sometimes frustrated with the pace of reforms, they largely accepted the small constitutional concessions handed out by the Raj every ten years or so when they could no longer be denied. These concessions were mainly in the form of representation in the legislative councils in Calcutta and in the provinces. However, a major transformation of the Raj occurred during World War I as authorities in London and Delhi finally came to accept a new goal for the Raj; the British would guide India to self-government. The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms included the expansion of the councils, the establishment of a system of 'dyarchy', or shared governmental responsibility between British officials and elected Indian ministers, and a vastly expanded franchise. However, embedded in the reforms was another process which would influence the shape that the Indian state would take after 1947, it was called 'Indianisation'.

Prior to World War I less than 5% of the officers of the heaven born Indian Civil Service were Indians, only a few Indian policemen had ever been promoted to senior posts in the Indian Police, and there was no way for Indians to rise as officers of the Indian Army. Each of the services had been comfortable in its role; the British officer of the Indian Civil Service would supervise the Indian clerk, the British officer of the Indian Police would direct the Indian constable and the British officer of the Indian Army would lead his loyal Indian sepoys. However, the order came from above to induct Indian officers into the senior ranks of the services as a part of the new commitment to self-government and the 'Indianisation' of the state. That old imperial hierarchy would be broken as Indians joined British officers in the Indian Civil Service, Indian Police and Indian Army. Each service put up varying degrees of resistance, yet after a slow start in the 1920s the services did become Indianised throughout the 1930s and early 1940s to the point at which around half the elite officers of the Raj were Indians.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj»

Look at similar books to The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Ring of Services: The Story of a Very Indian British Raj and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.