2020 Barbara Ellen Smith

Originally published in 1987 by Temple University Press.

This edition published in 2020 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-64259-393-8

Distributed to the trade in the US through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution (www.cbsd.com) and internationally through Ingram Publisher Services International (www.ingramcontent.com).

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please call 773-583-7884 or email for more information.

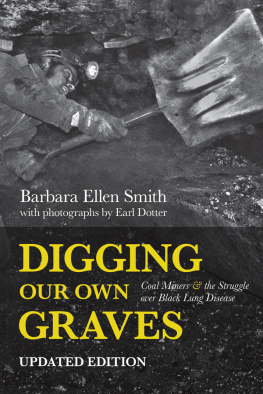

Front cover photo and photo gallery section Earl Dotter.

Cover and text design by Eric Kerl.

Portions of certain chapters appeared earlier in article form: Barbara Ellen Smith, Black Lung: The Social Production of Disease, International Journal of Health Services 11, no. 3 (1981): 343-59, Baywood Publishing Co., Inc. (first reproduced under the same title by the International Institute for Comparative Social Research, Berlin, West Germany); Barbara Ellen Smith, History and Politics of the Black Lung Movement, Radical America 17, nos. 2-3 (1983): 89-109; Barbara Ellen Smith, Too Sick to Work, Too Young to Die, Southern Exposure 12, no. 3 (MayJune 1984): 1929. All are reprinted by permission. George Sizemore, Drill Man Blues, in George Korson, Coal Dust on the Fiddle: Songs and Stories of the Bituminous Industry (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1943), 56-57 is printed by permission of Mrs. Rae (George) Korson.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

To coal miners and their families all over the worldAll royalties from the sale of this book go to support

the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum.

www.wvminewars.com

Black lung, black lung, oh your hands icy cold,

As you reach for my life and you torture my soul;

Cold as that water hole down in that dark cave,

Where I spent my lifes blood diggin my own grave.

Black Lung, by Hazel Dickens

Preface

Digging Our Own Graves, first published in 1987, concluded with an ominous prediction: Black lung disease awaits the younger generation of coal miners who are now at work underground. Would that I had been wrong! Today, not only do coal miners still suffer from this lethal but preventable lung disease, they do so at younger ages, some even in their thirties, and they are contracting the most advanced form of black lung at the highest rates ever recorded. More than fifty years after the US Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 imposed a respirable dust standard on the coal industry, designed to prevent black lung, why do such carnage and suffering persist? This updated version of the original book seeks answers to that question.

My own introduction to black lung began in the winter of 19711972, when I came to West Virginia to work for the Black Lung Association. I was barely twenty years old. Extraordinary political transformations were in the making: coal miners, miners wives, and widows were challenging powerful institutions that had once commanded their acquiescencethe hierarchy of the United Mine Workers, the coal operators association, county political machines, and the Social Security Administration. For a young college student from the Midwest, these developments in the mountains of West Virginia beckoned with a romantic excitement. Besides, the mountains were my ancestral homeplace; now I could return to them, not on a summer vacation in the backseat of the family car, but on my own.

Working with the older coal miners and impatient young organizers who made up the Black Lung Association at that time was a formative political experience for me. Coming from a long line of southern subsistence farmers and circuit-riding preachers, I was instilled with a righteous, if vague, sense of populism that made me eager to join the struggles of working people. But neither my political heritage nor my exposure to campus radicals prepared me for what I found in the coalfields of West Virginia: above all, the stark boundaries and clear perceptions of class antagonism. Virtually every coal miner over the age of sixty-five proudly claimed to have fought in the battle of Blair Mountain with a machine gun in 1921 to bring the union into southern West Virginia. They were up against the combined forces of coal company guards, the state police, county sheriffs and their deputies, aerial bombers, and, ultimately, the US Army. I was dumbfounded.

Fortunately, it didnt occur to me to write about any of these experiences until my age and the changing times helped to deepen my understanding of what they might mean. In 1978, more than six years after I had first worked for the Black Lung Association, I began the research for a dissertation on the black lung movement. The political atmosphere was altogether different. A reform movement in the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) had arisen, succeeded in a special election for leadership of the union, then disintegrated; the black lung movement had seemingly disappeared; and a storm of reaction was sweeping the Appalachian coalfields. The setbacks were frightening, but they made possible a more sober and critical perspective on the earlier period of upheaval.

I began this book as a labor history, asking obvious questions that seemed most important at the time: Why did the movement end this way? What did it accomplish? How did it fail? Who or what was to blame? As I dug deeper into the history of the black lung movement, however, these apparently clear-cut questions about victories and defeats began to seem ambiguous, even misleading. The assessment of whether the movement had succeeded or failed depended a great deal on whose goals were used as the standard of measurementand goals varied considerably among different participants. Moreover, what the larger political culture defined as the movements greatest accomplishments often turned out to be mainly symbolic; they represented the visible outcomes of formal processes of reform (the passage of legislation, for example), but in and of themselves did not necessarily signify substantial and lasting change. The simplicity of my original questions faded as the labels of victory and defeat, success and failure, appeared more and more ephemeral. The central analytical problems increasingly seemed to involve the maddening complexity of social change itself, which prevented any person or group from controlling the course or outcomes of this movement.

As I delved further into the reforms sought and controversies engendered by the black lung movement, it became apparent that the movement was more than an important episode of labor resistance. At

As a result of these and other shifts in emphasis, this book is a hybrid. It draws on diverse theoretical traditions in order to analyze not only the organization and development of the black lung movement, but also the history and conflict that underlie the brutal fact of coal miners diseased bodies. Beginning with how and why black lung originates in the workplace, this book also explores the medical history of the disease and the conflicting meanings that miners and certain physicians, lawyers, and government administrators invest in black lung.