2012 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2011047787

ISBN 978-1-60635-119-2

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

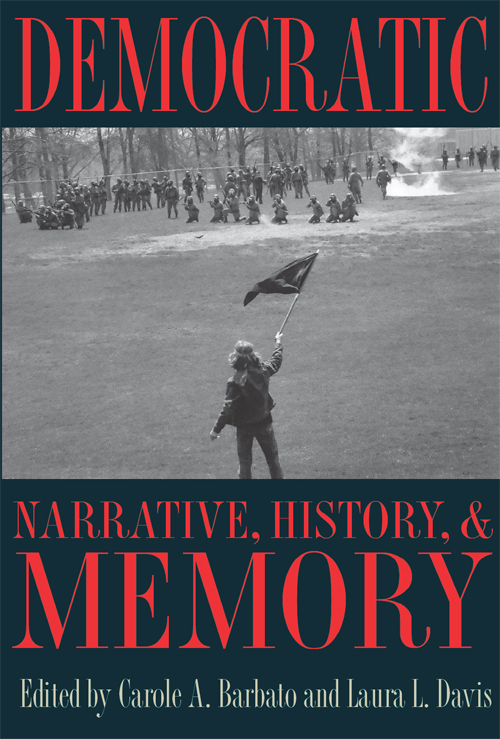

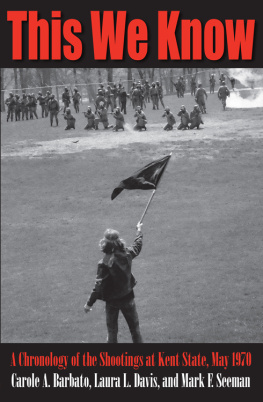

Democratic narrative, history, and memory / edited by Carole A. Barbato and Laura L. Davis.

p. cm. (Symposium on democracy series)

Essays based on and revised from presentations at the 2009 Kent State University Symposium on Democracy.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60635-119-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Kent State Shootings, Kent, Ohio, 1970Congresses. 2. Collective memoryUnited StatesCongresses. 3. Mass mediaSocial aspectsUnited StatesCongresses. I. Barbato, Carole A.

II. Davis, Laura L. III. Kent State University Symposium on Democracy.

LD 4191.072 D 46 2012

378.77137dc23

2011047787

16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

CAROLE A. BARBATO AND LAURA L. DAVIS

On May 4, 1970, an international spotlight focused on Kent State University after a student protest against the Vietnam War and the presence of the Ohio National Guard on campus ended in tragedy. Twenty-eight guardsmen fired sixty-seven shots in thirteen seconds. They killed Kent State students Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer, and William Schroeder and wounded nine other students, permanently paralyzing Dean Kahler.

The demonstration at Kent State marked a climax of the student activism and protest of the 1960s, a historical period encompassing the shootings at Kent State. The student protest movement was rooted in the civil rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s.1 On college campuses, the generation gapthe divide between generations in lifestyle, culture, politics, and valuesof the 1960s also was strongly felt. Those in positions of authorityparents, campus administrators, politicians, and law enforcement officialssquarely lined up on one side of the divide, with rising numbers of students on the other.

On May 4, the Ohio National Guard, called into town by Kents mayor, literally lined up on campus on one side of the grassy central area known as the Commons. Students gathered five hundred feet away at the campus Victory Bell. Most students were observers; many felt aligned with the general counterculture movement; some were campus activists. Many students were consciously exercising their First Amendment rights of freedom of assembly and freedom of speech as they gathered for the May 4 rally.

In a statement read by press secretary Ron Ziegler, President Richard Nixon responded to the shootings by commenting, This should remind us all once again that when dissent turns to violence it invites tragedy, an assertion of authoritarian values seen by many as lacking in sympathy.2 For a large proportion of Americans, from members of Congress to the average citizen on both sides of the generation gap, the shootings constituted a watershed moment that changed their perspectives on the war in Vietnam. May 4, 1970, became the day the war came home in the American imagination, the day that American soldiers killed American children on U.S. soil.3 For college students, the shootings at Kent State spurred the largest national student strike in U.S. history. More than half the colleges and universities in the country (1350) were ultimately touched by protest demonstrations, involving nearly 60 percent of the student populationsome 4,350,000 people in every kind of institution and in every state of the union.4

What Nixon failed to see, his staff recognized: the shootings at Kent State became one of the major symbolic events of the Vietnam War as well as the 1960s era, marking the beginning of the end of Nixons presidency, as his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, noted.5 By January 1973, when Nixon announced the effective end of U.S. involvement, Vietnam War historian Mark Barringer writes, he did so in response to a mandate unequaled in modern times.6 During these years, the legal aftermath of the events of May 4, 1970, was well on its way to becoming, as Kent State legal scholar Thomas Hensley explains, one of the longest, costliest, and most complex set of courtroom struggles in American history, setting civil rights precedent in the U.S. Supreme Court.7

In 2000, on the thirtieth anniversary of the event, Kent State University established an annual Symposium on Democracy. The symposium was founded as a living memorial to honor the memories of the four students who lost their lives in the May 4 shootings, with an enduring dedication to scholarship that seeks to prevent violence and to promote democratic values and civil discourse. This volume presents a collection of essays based on and revised from presentations at the 2009 symposium. Through a range of disciplinary lenses, these essays explore the complex relationships among experienced events, memory, and portrayal of those events in order to probe the deepest questions of human experience. While connections among the essays cross over from multiple directions, they have been gathered in three groupings that offer one set of possibilities for making meaning. Essays in the first group move from the particular history of May 4, 1970, to eternal concerns of peace and violence, silence and giving voice. Those in the second group address the part played by corporateand noncorporate, if you willmedia in shaping public memory and raising public consciousness. The essays in the final grouping examine acts of remembrance and reconciliation within local communities and the long history of discrimination existing within the national American community. Like the first two groups of essays, this group directly and indirectly proposes ways in which we can move toward social justice.

On the occasion of the tenth annual symposium, historian Jay Winter addressed the Kent State community as the silence-breakers, who recognize, with Joseph Brodsky, that the past wont fit into memory without something left over. It must have a future. Winter noted of the Kent State community that it is our achievement to shape that future through framing of active knowledge in this place and at this time about the injustices that occurred here.8

For more than forty years, the Kent State community has answered the claim that other human beings have on us, so that we preserve the stories of those who have been lostboth to honor the lost and to reveal universal meanings.9 We at Kent State are negotiating, in a literal sense, the space between memory and history, between social remembering and historical analysisas Jerry M. Lewis, in his essay in this volume, applies the terminology of James Wertsch. For the 2009 symposium, scholars national and international were invited to join us in thinking through how to preserve Kent States history for future generations, so as to respectfully acknowledge the past and to serve the future.10 The scholarly examinations of the 2009 Symposium on Democracy informed the thinking, planning, and decision making for a May 4 Visitors Center. The two main features of this center are a guided walking tour of the seventeen-acre historic site and a permanent exhibit. The walking tour provides visitors the facts of the event, which had become draped in myth and misunderstanding.11 Acknowledging the many voices and multiple perspectives regarding the events of May 4, the exhibit invites visitors to explore those facts within the social and historical context of the times, in order to better understand the events of that day and to reflect on their impact and meaning for today.