Originally published in 1960 by Harper and Row

First published 2011 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2011 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2010051969

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

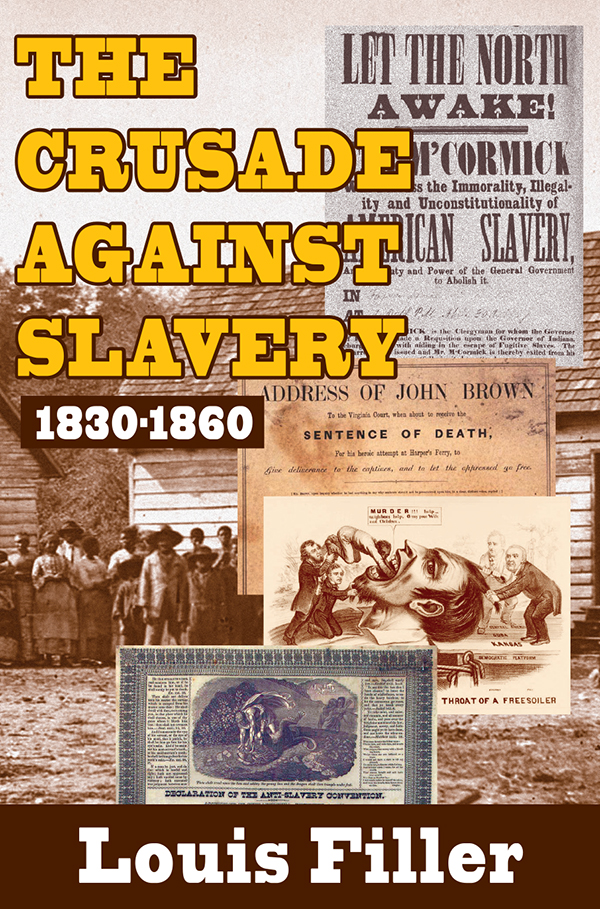

Filler, Louis, 1911-1998.

The crusade against slavery, 1830-1860 / Louis Filler.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Harper, 1960.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-4219-8 (alk. paper)

1. Antislavery movements--United States--History--19th century. I. Title.

E449.F493 2011

326.0973--dc22

2010051969

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-4219-8 (pbk)

IN THAT ferment of reform in which the generation of Americans before the Civil War participated, the movement to abolish the peculiar institution still holds the central place. It was an age of humanitarian preoccupations, in which reformers ranged over the whole spectrum of social change. They seldom advanced a single cure for all social ills. Instead, they turned from bankruptcy reform to public education, from womens rights to temperance and vegetarianism, from spiritualism to the abolition of capital punishment. Above all, the more earnest and courageous were ready and anxious to come to grips with the slavery question.

In the truest sense of that overworked term the reformer of that era was a radical, a radical in the sense in which Ralph Waldo Emerson would have used that term. In a famous public address delivered in 1841, Emerson declared that the idea which now begins to agitate society has a wider scope than our daily employments, our households, and the institutions of property. We are to revise the whole of our social structure, the state, the school, religion, marriage, trade, science, and explore their foundations in our own nature; we are to see that the world not only fitted the former men, but fits us, and to clear ourselves of every usage which has not its roots in our own mind.

To these root-and-branch changes the reformer, notably the anti-slavery advocate, brought a sense of the vitality of American democracy, a broad humanitarianism, a Utopian vision, an evangelical fervor, andit seemed to his opponentsa holier-than-thou attitude. To remodel his world he appealed to reason; he invoked the aid of religion; he engaged in enormous factual research; he fought his battles in the courts as well as in the press; he resorted to political action; he took grave personal risks; he engaged in conspiracies; and at times he even used violence. If he did not bring about a civil war he made that conflict appear irreconcilable. Recognizing slavery for what it was, an evil and morally indefensible institution, he invested the struggle over slavery in the territories and the enforcement of the fugitive slave law with moral overtones.

The learned author of this volume regards abolition as the ultimate reform, and tests the sincerity of reformers by their willingness to confront the supreme moral issue of that age. What unfolds in this book is the case against slavery, rather than an analysis of the institution itself, a subject which is reserved for another volume in this series. Admittedly, abolitionists were propagandists rather than objective reporters. They depicted slavery at its worst. They overemphasized plantation slavery and relied heavily on the slave code without adequate verification by reference to court records and common usage. They generally ignored the fact that a significant segment of the southern labor force of both races operated under varying degrees of compulsion, legal or economic, in a twilight zone of bondage. Many of them were blind to the iniquities of the system of wage slavery in their own back yards. Nevertheless, despite their partisanship and extravagance they roused the conscience of an important segment of the nation and dramatized the issues of human freedom and equality, still central problems of our own revolutionary age.

All those renowned for their impassioned battle against slavery are given their due in this volume, and many lesser figures have been rescued from undeserved oblivion. The author does not follow some recent scholars who would disparage Garrison and give a larger role to the western abolitionists. Garrison emerges from these pages as the seminal figure in antislavery, but significant roles are awarded to William Jay, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, Theodore Dwight Weld, the Lane Theological group and the Oberlin College group, among others, as well as such notable political abolitionists as John Quincy Adams and Joshua R. Giddings. Professor Filler has buttressed his conclusions by exhaustive research among the unpublished papers of antislavery leaders. He has uncovered little-known tracts and pamphlets, and delved through formidable files of abolition periodicals. His bibliography will be a treasure trove to future researchers in this field.

This volume, which is one of the New American Nation Series, a comprehensive and co-operative survey of the history of the area now embraced in the United States from the days of discovery to our own time, is concerned chiefly with the antislavery movement and only incidentally with other reforms of that age. These other humanitarian movements will come into larger focus in the volume dealing with the cultural life of the ante-bellum years. Other aspects of the times, such as western expansion, political issues, and constitutional problems, are each considered in separate volumes in the series.

HENRY STEELE COMMAGER

RICHARD BRANDON MORRIS

IN THE 1830s and after the winds of reform shook the United States more furiously than ever they had since the Revolution. Not only were there more causes than before, but, in an era of the rise of the common man, they affected more people. In such an atmosphere of unrest, the status of the Negro, both enslaved and free, became an increasingly urgent and pre-eminent issue, and, in the end, divided the nation.

The abolition and reform movements were complex by nature, carrying emotional overtones, and associated with spectacular events. It was not possible to present disinterested analyses of their content and direction, either in their time or for a long time thereafter. The growth of free soil and the struggle to preserve the Union made reform seem less important, and confused the definition of abolition. In the post-Civil War period the reformers, once bound together by concern for the slave, by free speech, temperance, education, womans rights, and other causes, tended to separate, each to pursue his own specialty. This growing emphasis on specialists made it increasingly difficult to accept the fact that one could agitate for womans rights,