Indigenous Bodies, Maya Minds

IMS Studies on Culture and Society Series

VOLUME 1

Symbol and Meaning behind the Closed Community: Essays in Mesoamerican Ideas

edited by Gary H. Gossen

VOLUME 2

The Work of Bernardino de Sahagn: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico

edited by J. Jorge Klor de Alva, H. B. Nicholson, and Eloise Quiones Keber

VOLUME 3

Ethnographic Encounters in Southern Mesoamerica: Essays in Honor of Evon Zartman Vogt, Jr.

edited by Victoria R. Bricker and Gary H. Gossen

VOLUME 4

Casi Nada: A Study of Agrarian Reform in the Homeland of Cardenismo

by John Gledhill

VOLUME 5

With Our Heads Bowed: The Dynamics of Gender in a Maya Community

by Brenda Rosenbaum

VOLUME 6

Economies and Politics in the Aztec Realm

edited by Mary G. Hodge and Michael E. Smith

VOLUME 7

Identities on the Move: Transnational Processes in North America and the Caribbean Basin

edited by Liliana R. Goldin

VOLUME 8

Beware the Great Horned Serpent!: Chiapas under the Threat of Napoleon

by Robert M. Laughlin

VOLUME 9

Indigenous Bodies, Maya Minds: Religion and Modernity in a Transnational Kiche Community

by C. James MacKenzie

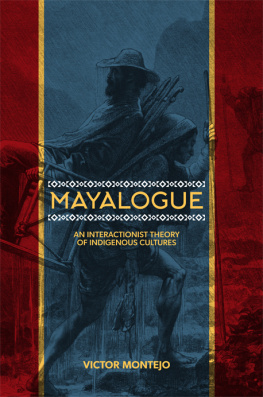

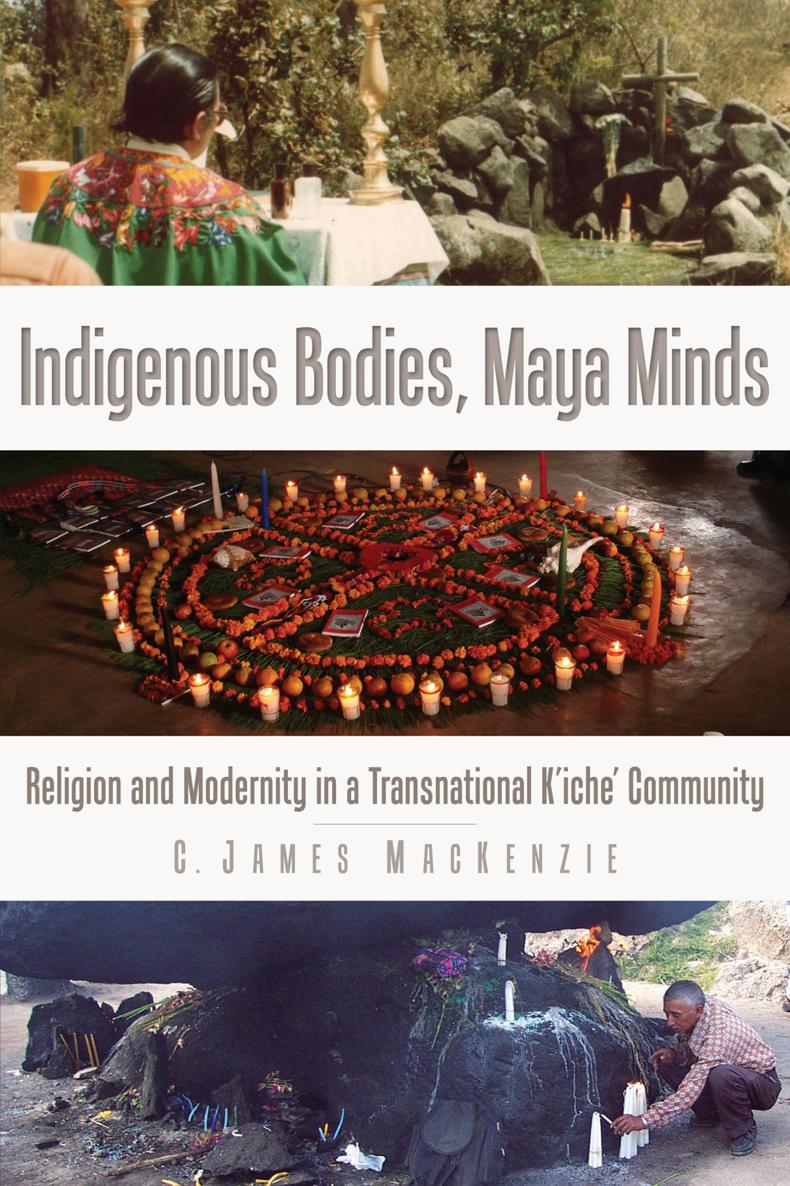

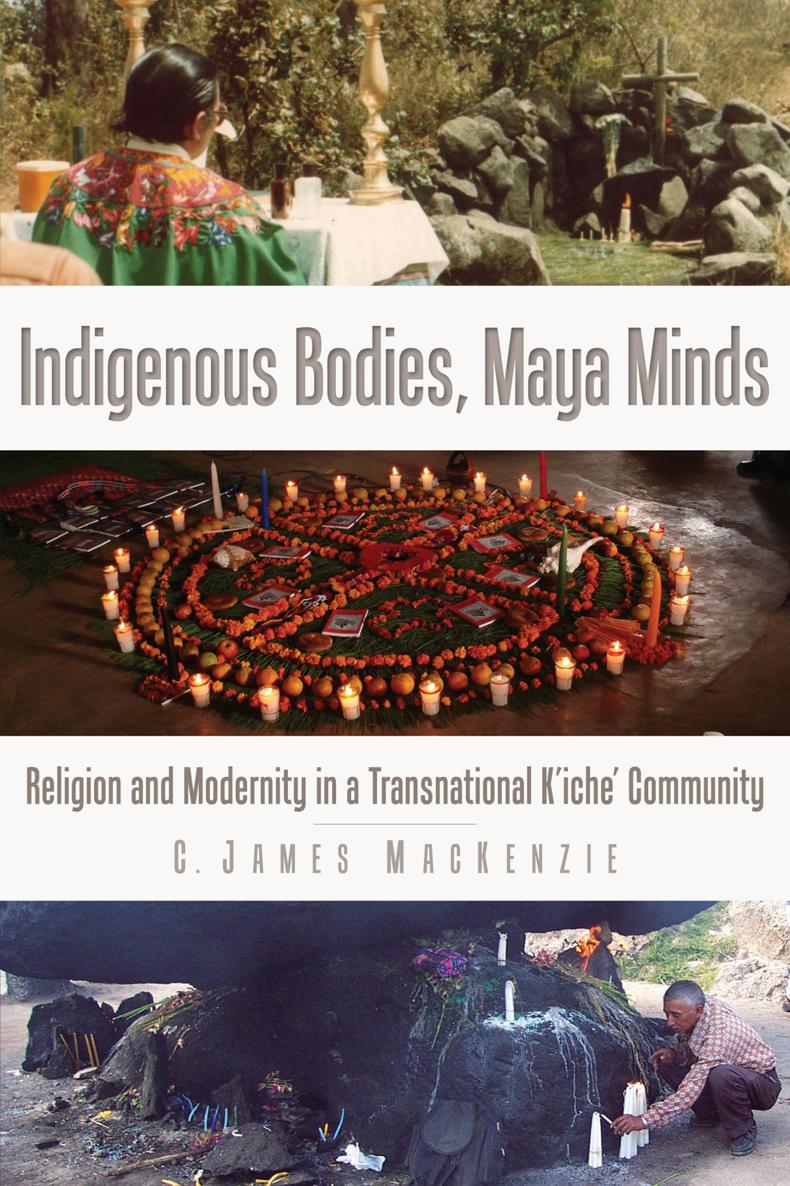

Indigenous Bodies, Maya Minds

Religion and Modernity in a Transnational Kiche Community

C. James MacKenzie

University Press of Colorado

Boulder

Institute for Mesoamerican Studies

Albany

2016 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

Institute for Mesoamerican Studies

Arts and Sciences

233 University of Albany, SUNY

1400 Washington Avenue

Albany, NY 12222

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 978-1-60732-393-8 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-556-7 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-394-5 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

MacKenzie, C. James.

Indigenous bodies, Maya minds : religion and modernity in a transnational K'iche' community / C. James MacKenzie.

pages cm

Summary: "MacKenzie examines tension and conflict over ethnic and religious identity in the K'iche' Maya community of San Andres Xecul in the Guatemalan highlands, and considers how religious and ethnic attachments are sustained and transformed through the transnational experiences of locals who have migrated to the United States" Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-60732-393-8 (hardback : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-556-7 (pbk) ISBN 978-1-60732-394-5 (ebook)

1. Quich IndiansGuatemalaSan Andrs XeculSocial conditions. 2. Quich IndiansGuatemalaSan Andrs XeculEthnic identity. 3. Quich IndiansGuatemalaSan Andrs XeculReligion. 4. Quich IndiansGuatemalaSan Andrs XeculMigrations. 5. Quich IndiansRelocationUnied States. 6. San Andrs Xecul (Guatemala)Emigration and immigration. 7. United StatesEmigration and immigration. I. Title.

F1465.2.Q5M34 2015

972.8100497423dc23

2015010758

Cover illustrations: courtesy of Padre Toms Garca (top); photo by author (middle, bottom).

Foreword

It was after a particularly long ceremony, a xukulem, at Ixchimche in January 2005, that I found myself at a table of ajqijathe Kiche and Kaqchikel name for Maya religious practitioners. As we sat nursing our Gallo beers and waiting for our food, steaming-hot beef caldo and tortillas, we were in that post-xukulem state of being both exhausted and energized by the experience. Conversations that went from Spanish to Kaqchikel to Kiche to Tzutijilthe languages of the ajqija at the tablewandered over various topics, rarely skirting what happened at the xukulem. The lunch participants were experienced ajqija, and most could understand the various languages being spoken.

As I sat there with soot from burned incense and candles on my face, trying to keep up with the rapid language code-switching and diverse topics that floated into and out of the conversation, it struck me as profoundly significant that the talk around the table was more about the politics of being Mayain their respective communities, in Guatemala, in the worldthan Maya spirituality and religious practice. In fact, the xukulem itself was to address a variety of pressing environmental concerns that they and members of their communities had, particularly deforestation of the highlands and the contamination of Lake Atitln.

Iximche, the Kaqchikel city-stronghold that was beset and sacked by the Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado in 1524, has been a site of continuous Maya resistance, first to Spanish colonialism then to non-Maya state rule, for more than 500 years. It is an appropriate place for ajqija from various ethno-linguistic groups to gather and hold xukulem to address problems within their communities and their country. So it was not too surprising to listen to these ajqija debate about the state of the environment, the persistent discrimination of Mayas in Guatemalan society, and how to improve education and job opportunities for Mayas.

When lunch wrapped up and everyone was getting into their cars or catching a bus to go home, I remarked to Kawoq, the Kaqchikel ajqij who took me to the ceremony, that I thought it was odd that over lunch they did not really reflect on the actual ceremony and that I was surprised to learn that some of the ajqija were Protestants, rather than all being Catholics. His response was short, perhaps, because the intensity of the xukulem was finally starting to hit him but, maybe, because my comments did not merit much consideration.

Waqi [my Kaqchikel name], the xukulem is over, Kawoq bluntly told me. Lunch conversation was about living in the world. He added: You already knew that Protestants and Catholics participated in xukulem. There is nothing problematic about that.

At the time, I thought that this is what ethnographers needed to do, to focus on the politics around Maya religion and the more contemporary quotidian aspects of religious life, identity, and cultural politics rather than on the mechanics and practices of Maya religious life. In Indigenous Bodies, Maya Minds: Religion and Modernity in a Transnational Kiche Community, C. James MacKenzie does just that and more.

Much of now extensive ethnographic research on Maya spirituality and, more broadly, Mesoamerican religious practice, within which MacKenzie situates his case study of Kiche Mayas from San Andrs Xecul, Guatemala, has concentrated on what can be considered Mayas distinct nonmodern religious practices, those that illustrate in often dramatic, exotic ways how Mayas are different. Throughout his monograph MacKenzie converses with this scholarly literature thatdespite Spanish colonialism, national independence and revolutionary movements, and continually shifting global political economiesconcentrates on the deep cultural continuities of Maya religious ideology and practice. MacKenzies emphasis is more on Maya religion in the existential world that Mayas live. With eloquently written prose and rich ethnographic descriptions of life in Xecul, he explains the complexities of religious pluralism for Mayas, untangling for us non-Mayas the ways that religious praxis unfolds for people who live in multiple places and are caught up by global and transnational processes, yet continually make, remake, and renew that specific place, San Andrs Xecul, through religion, work, conflict, friendship, and kinship.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.