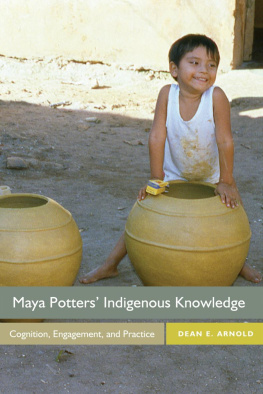

Maya Potters Indigenous Knowledge

Cognition, Engagement, and Practice

Dean E. Arnold

University Press of Colorado

Boulder

2018 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 978-1-60732-655-7 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-656-4 (ebook)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607326564

If the tables in this publication are not displaying properly in your ereader, please contact the publisher to request PDFs of the tables.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Arnold, Dean E., 1942 author.

Title: Maya potters indigenous knowledge : cognition, engagement, and practice / Dean E. Arnold.

Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Contents note from ECIP table of contents.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017021804| ISBN 9781607326557 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607326564 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Maya potteryMexicoTicul. | MayasMaterial cultureMexicoTicul. | Cognition and culture. | PottersMexicoTicul.

Classification: LCC F1435.3.P8 A755 2017 | DDC 972/.65dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017021804

Cover photograph by Dean E. Arnold

Preface

We live in a rapidly changing world that is replacing ways of life that have much to teach us. Like agricultural expansion and monocropping that are destroying biological diversity and hampering the ability of domestic plants to adapt to changing conditions, globalization is destroying indigenous knowledge that can provide solutions more closely attuned to the culture and environment of traditional peoples than uncontextualized scientific knowledge (e.g., see ).

This book is an exploration of the indigenous knowledge of traditional pottery making in Ticul, Yucatn, Mexico, as it is expressed in the Maya language and behavior, and described in terms of material engagement theory (). In Ticul this knowledge is not changeless or shared outside of the population of local potters, but it is both cognitive knowledge, of which the potter is aware, and the actual practice and performance of that knowledge, of which the potter may have limited conscious awareness.

Defining this knowledge more specifically, Maya households and rooted in the pre-Columbian Maya past, but not necessarily unchanged from it.

The indigenous knowledge of Ticul potters is embedded in the native language of Yucatn, Yucatek Maya, and is usually, but not always, labeled in that language, often with subtleties unknown and unused in Spanish. Some knowledge of that language is essential to grasp the meanings that someone from outside the culture might miss. Translation, of course, does help, but it can obscure distinctions that the natives themselves make. An example of this difference involves the meanings of the Maya term sah kab, which potters freely translate as white powder, or is geologically identified as marl. Transliterated as sascab in Spanish, this phrase refers to a material widespread in Yucatn, but the hispanicized word as well as its geological reference obscures a variety of meanings essential for understanding potters indigenous knowledge (see ).

Learning and using Maya indigenous knowledge gave me a great sense of personal satisfaction, and learning conversational Yucatek Maya brought surprising consequences. I had spent six months in Yucatn in early 1965 learning about pottery firing, and in the course of that experience learned both conversational Spanish and some Yucatek Mayaparticularly that related to making pottery. Returning to Ticul in January 1966, I was walking toward a house of one of the potters when a man stopped me and asked me a standard conversation-starting question in Yucatek Maya. I immediately responded in Maya, but after doing so, I realized that I had given the wrong answer. I corrected myself in Maya, and apologized in Spanish, but he responded by saying: Its OK. Youre Dean (or din as they called me). You know Maya.

His compliment stunned me. I had never see this man before, and I had no idea who he was. Yet, he knew me and knew my name. Indeed, I was so surprised that I never forgot the incident.

At the time, however, I contemplated what had happened. In 1966 Yucatn was still very isolated from the Mexican heartland, and non-Yucateco Mexicans were not highly regarded. They were called huachis because the word mimicked the squeaking sound of sandals of the highland mercenaries that invaded Yucatn in the years following the Mexican revolution of 1910 (see , 150).

On the other hand, Yucatecans regarded North Americans with a genuine fondness. This affection seemed to have its roots as much in the distaste for those from highland Mexico as from their desire in the mid-nineteenth century to be independent from the central government of Mexico, secede from the Mexican nation, and become part of the United States ( and thus was greatly appreciated. The man I encountered must have heard that there was a gringo who, in the process of working with potters, was learning Maya.

When I returned to Yucatn in 1984, however, the culture had changed. Most obvious was the presence of the Mexican central government, along with the national culture from the heartland. Yucatek Maya was starting to disappear, and in Ticul, at least, children were discouraged from using it. Perhaps emblematic of this central Mexican dominance was that I never heard the term huachi again.

Is there a true indigenous knowledge, or is it an illusion? Some criticize the notion of traditional knowledge, as if it went back into time immemorial and was immutable. Such critiques, of course, are straw men because traditional knowledge is changing even though its roots may be centuries old. Recognizing that indigenous knowledge and its practice in making pottery have changed over the last fifty years does not mean that this knowledge is so flexible, changeable, and relative that it is unknowable and cannot be discovered.

In many respects there is an objective way of establishing that some of this knowledge is, in fact, traditional, ancient, and goes back centuries. In Ticul, for example, the social memory of the sources of raw materials is verified by archaeological evidence that indicates that they extend back 1,000 years to the Terminal Classic Period ( ad 8001100; in this volume).

By way of contrast, the firing of pottery represents a more complicated picture of traditional indigenous knowledge. The kiln used by the Ticul potter, for example, is of probable Moorish origin and is consistent with the origin of most of the postconquest Spanish immigrants who came from Andalusa, in southern Spain, a region that Islamic culture dominated for more than 800 years. Nevertheless, this apparently Moorish kiln in Ticul has a Maya name (

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.