Black Hills Forestry

A History

John F. Freeman

University Press of Colorado

Boulder

2015 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freeman, John F. (John Francis), 1940

Black Hills forestry: a history / John F. Freeman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-60732-298-6 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-60732-299-3 (ebook)

1. Forests and forestryBlack Hills National Forest (S.D. and Wyo.)History. 2. Black Hills National Forest (S.D. and Wyo.)History. I. Title.

SD144.S63F74 2014

577.309783'9dc23

2013037187

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover photograph Kari Greer Photography

Preface

In 1950 Howard R. Lamar, an eminent historian of the American West, wrote that no adequate study of the Black Hills exists. Since then, volumes of technical articles, monographs, and some readable books have been published on various aspects of the Black Hills, such as natural history, gambling and gold mining, timbering and sawmills, tourism, and Mount Rushmore. To date, however, no study has focused on the history of the Black Hills National Forest, its centrality to life in the region, and its preeminence within the national forest system.

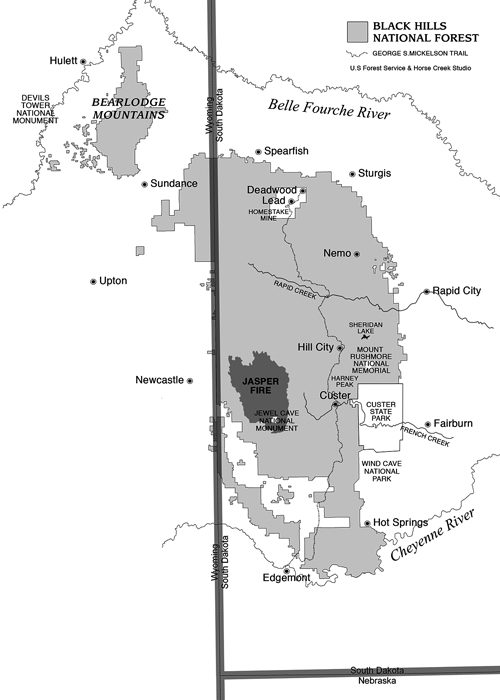

My interest in the Black Hills came about through volunteer work in the Wyoming governors office. I found myself in Hulett, population 400, called to advise residents on how a refurbished former school building might serve as the physical center for a community effort to stabilize and diversify the local economy. Hulett depended on the forest, with most working residents employed at the Neiman sawmill or by logging contractors. In 2007 I had no idea that the Black Hills National Forest was arguably the most commercialized national forest in the nation. On my first tour, I was struck immediately by the crass commercialism within and around the national forest.

To be perfectly candid, I arrived in the Black Hills with an ideologically tinged view of national forests. As a child, I had been taken into the Ozark National Forest for hiking and picnicking. At age fourteen, I spent a summer tramping with my dog in the Medicine Bow National Forest near Fox Park. I returned to Wyoming permanently during the height of the clear-cutting controversy, siding on aesthetic grounds with anti-timbering advocates. It had yet to occur to me that a forest intensively cut for more than a century could be managed back into some form of natural health or that the forest, like any living organism, could not be separated from its dependent and interdependent partsincluding loggers and miners, hunters and hikers, private property in-holders, and the residents of communities within the forests boundaries.

Working in the office of a proactive governor certainly helps one shed ones righteousness and navet because one is under pressure to solve, or at least lessen the severity of, problems. In addition, it occurred to me that my prior work building charitable endowments was similar in spirit to the work of a forester managing public forests. In both cases, we carry a picture in our mind of what we expect our community or our forest to look like in a hundred years, and we know the major results of our work will not show until after we are gone.

My decision to write about the Black Hills National Forest was in part fortuitous and in part historical. From my prior study of High Plains horticulture, I knew that the Black Hills were the main seed source of ponderosa pine, the most popular conifer planted on the High Plains, and that Nebraskas Charles E. Bessey had directed his early botany students to the Black Hills because of the unusual mixture of floristic zones: Rocky Mountain Coniferous, Great Plains Grassland, Eastern Deciduous, and Northern Coniferousall within a relatively small, topographically isolated area.

With my own interest in French rural historybe forewarned that I am neither an ecologist nor an environmental historianI was intrigued that Gifford Pinchot had pursued his formal forestry training in France. He knew about the French governments successes with restoring mountain forests and became captivated by the notion of the duty of governments to protect public forests. In a troublesome parallel to his European findings, Pinchot had learned about deforestation around mining camps in the Black Hills. He knew firsthand about the favorable topography and understood the timbering potential of the predominant ponderosa pine (chapters 1 and 2). By adapting science-based European forestry, he intended to transform the Black Hills Forest Reserve into the nations preeminent well-managed forest.

But first, Pinchot helped South Dakota senator Richard F. Pettigrew with the landmark Forest Management Act, convinced Homestake Mining Company to purchase the first stands of federal timber, and sent the entomologist Andrew D. Hopkins to identify the insects damaging vast stands of marketable timber and suggest measures for their control. Early forestry documented by Pinchots personal representatives in the Black Hills provided material for his famous Use of the National Forest Reserves. By winning over the Black Hills stock grower and influential Wyoming member of Congress Franklin W. Mondell, Pinchot brought about the consolidation of ownership and management of the forest reserves into the US Forest Service (chapters 3 and 4).

Over a period of fifty years (1910s1950s), the Forest Service in the Black Hills did everything possible to ensure the largest possible sustainable harvests of commercial timber, with the criteria of sustainability worked out by well-trained and well-intentioned supervisors and their staffs. Managing for timber production encompassed far more than preparing sales, marking timber, and monitoring logging operations. It also included prevention and suppression of wildfires, thinning to encourage growth, and the construction of roads to enable operators to reach farther and farther into the forests. From the start, local businesses sought to capitalize on the beautiful scenery. The advent of automobile travel accelerated that effort, despite the Forest Services reluctance to promote recreation. Nonetheless, the Forest Service was pressed to transfer land to the State of South Dakota for Custer State Park and was forced by congressional action to give up full control over land designated as the State Park Game Sanctuary. Though never so stated, the bitterest pill was the transfer of 1,200 acres within the most mountainous region of the national forest to the National Park Service for Mount Rushmore National Memorial (chapters 57).