Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2016 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Eileen Nizer

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Saeki, Manabu.

The phantom of a polarized America : myths and truths of an ideological divide / Manabu Saeki.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5907-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-5909-7 (e-book)

1. Divided governmentUnited States. 2. Party affiliationUnited States. 3. Political partiesUnited States. 4. Polarization (Social sciences)United States. 5. IdeologyUnited States. 6. Political cultureUnited States. 7. Politics, PracticalUnited States. 8. United StatesPolitics and government. I. Title.

| JK2261.S24 2015 |

| 320.50973dc23 | 2015004949 |

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Divided nation. Polarized America. These are the terms conspicuously used when the media, party elites, and voters describe the United States today. Every day, various news media report a profound split in the populace and the government on numerous issues, and the nation appears to be sharply divided based on partisanship. On December 17 to 19, 2010, CNN Opinion Research Corporation asked poll respondents whether they hoped that President Barack Obamas policies would succeed or fail.

Researchers note that partisan differences on political issues have significantly widened in past decades. A survey conducted by Pew Research Center reports that the average difference between the opinions of Republican and Democratic voters on 48 political and social issues stands at 18 percentage points as of 2012. the size of the gap in a similar survey conducted in 1988. Brewer and Stonecash (2007) posit that the increasing income inequality and the emergence of cultural issues heightened the political divide along party lines in the nation. The analysts note that since 1960, the income of the high-income Americans has been increasing whereas the income of low-income Americans is declining. Also, since the 1980s, various cultural issues have emerged, such as homosexuality, abortion, gun control, church-state relationship, and so on. Brewer and Stonecash (2007) explain that these cultural controversies, in addition to the deep division in economic class, split the populace along party lines, which have propelled polarized policy alternatives on such cultural issues.

As for the government, division between party elites appears to be even deeper than the division in the populace today. During the 2008 presidential election, both the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates frequently pledged to build bipartisanship. Nonetheless, on February 11, 2009, less than a month after the inauguration of President Obama, the newly convened 111th Congress narrowly passed a $787 billion economic stimulus package with no support from any Republican House members and the support of only three Republican senators. Thus, in just a few weeks after the inauguration of the new president and Congress, it was revealed that the American government remained severely divided. On December 24, 2009, the Senate passed a landmark law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. This so-called Obamacare bill was passed by a vote of 60 to 39, a vote divided along party lines. Although all Democratic senators and two Independents voted for the legislation, all but one Republican senator voted against the bill. Similarly, the House vote on the measure was also divided along party lines. The House passed the bill with a vote of 219 to 212 on March 21, 2010, with all of the Republicans members voting against the measure. The next day, the House Republicans introduced a bill to repeal the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Furthermore, on December 15, 2010, the Democratic-majority House passed the Dont Ask, Dont Tell Repeal Act to end barring openly homosexual persons from military service, with the support of only fifteen Republican members. Three days later, the Senate passed the measure with the support of only eight Republican senators.

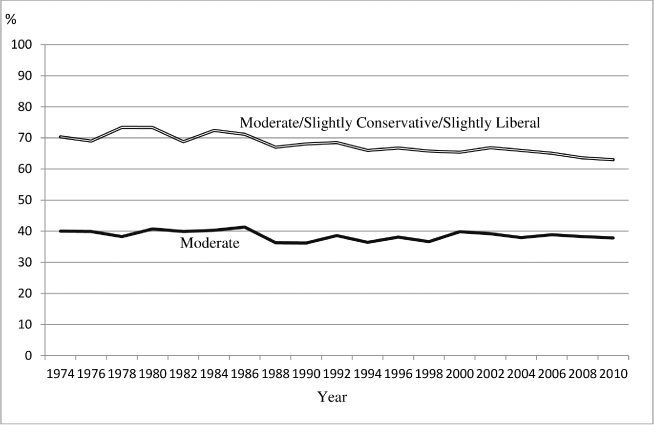

Thus, the ideological schism currently appears to be at its pinnacle in the realm of the public, as well as the government. However, there are some indicators that seem to proffer a revision in the myth of a polarized America. Pertaining to the American electorate, for instance, some studies indicate that a majority of voters remain moderate and the overall ideological proclivity of the populace has not changed much in the past few decades (Fiorina and Abrams 2009; Fiorina et al. 2011; Fiorina and Levendusky 2006; Hetherington 2009; Levendusky 2009). Fiorina et al. (2011) examine the preferences of voters on various controversial issues, including abortion and gay marriage. The findings suggest that the preferences of voters have been stable for decades and most voters have been moderate.

does not illustrate any significant decrease in the percentages of the aforementioned groups. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, overall, there was no significant change in voters ideology in the past few decades, and a majority of the electorate has always been moderate, slightly liberal, or slightly conservative.

Figure 1.1. Percentage of Moderate, Slightly Conservative or Slightly Liberal: GSS 19742010

Fiorina et al. (2011) expound that the appearance of an ideological split in the public is due to the elevated homogeneity in voters ideology within parties, which resulted in greater distance in the voters preferences between parties (Fiorina and Abrams 2009; Fiorina et al. 2011; Fiorina and Levendusky 2006). In this party-sorting thesis, the Fiorina school posits that whereas the aggregate distributions of conservative, liberal, and moderate voters have remained similar for decades, conservative voters in the Democratic Party and liberal voters in the Republican Party diminished, thereby extending the ideological difference between Democratic and Republican voters.

As for party elites, scholars began to notice an increase in partisanship in the 1990s (i.e., Aldrich 1995; Bond and Fleisher 2000; Rohde 1991; Sinclair 1995). In 2013, Keith Poole studied the difference between Republican and Democratic parties in voting preferences in Congress, and noted that as of 2012 the polarization within the House and the Senate was at the highest level since the end of Reconstruction. While several scholars measured a degree of polarization in Congress with a difference between the two parties on ideological indices, effectually none have studied the ideological shifts of the two parties separately. When researchers have studied the causes and effects of the ideological divide in Congress, they measured polarization as a unitary, monistic development. The tacit and untested premise was that both the Democratic and the Republican parties moved away from the ideological center. Thus, potentially differential dynamics for the ideological shifts of the Democratic and Republican parties in Congress, separately, were not studied.