Whistle Stops

Whistle Stops

Adventures in Public Life

Wilson W. Wyatt, Sr.

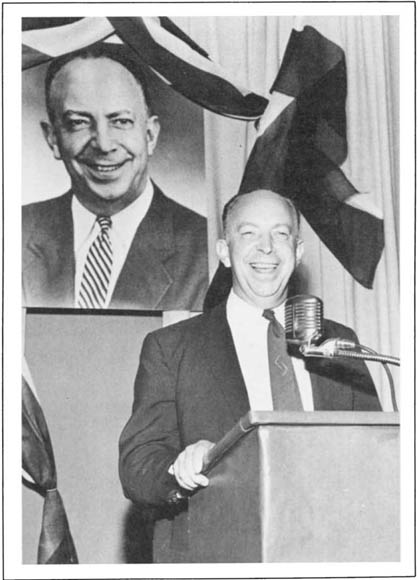

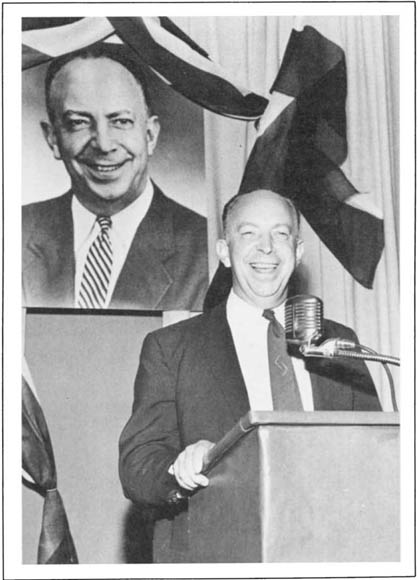

Frontispiece: Wilson W. Wyatt, Sr., campaigning

Photo Credits

Photographs in this book are from the authors personal collection except as indicated, by page number, below: Frontispiece, Lin Caufield; , United States Information Service-Tokyo.

Copyright 1985 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wyatt, Wilson W. (Wilson Watkins), 1905

Whistle stops.

Includes index.

1. Wyatt, Wilson W. (Wilson Watkins), 1905 2. DiplomatsUnited StatesBiography. 3. KentuckyLieutenant-governorsBiography. 4. MayorsKentuckyLouisvilleBiography. 5. United StatesForeign relations1945 . 6. United StatesPolitics and government1945 . 7. KentuckyPolitics and government1951 . I. Title.

E748.W97A39 1985 976.9040924 [B] 85-15066

ISBN: 978-0-8131-5543-2

For Anne, my complete partner

Contents

Illustrations

Wilson W. Wyatt, Sr., campaigning

Chapter 1

A Conversation with Trygve Lie

Vat is dis business about private practice of law? asked Trygve Lie in his deep Norwegian guttural. The Secretary-General of the United Nations was on the telephone trying to persuade me to take a position described by him as the under secretary-general of the United Nations. It was January, 1947, and I had just that day returned to Louisville to resume my law practice after spending five years away from itfirst as mayor of Louisville for four years and then as President Trumans National Housing Administrator and Housing Expediter. I had exhausted my savings and was convinced that a more extended departure from my profession could well mean the loss of it. Nevertheless, I responded to his urging by agreeing to turn right around and fly back East to talk out the situation with him. The United Nations building in New York had not yet been built and the headquarters was then at Lake Success, just outside the city on Long Island.

Trygve Lie was a large man whose cordial self-assurance matched the size of his body. With jovial charm he tried to persuade me that my training in the law, my service in local government as the elected wartime mayor of a major war production city, and my national experience in the appointed quasi-cabinet post under President Truman in launching the postwar housing program all constituted the ideal background for the position he was urging me to take. I demurred and explained what I felt was the financial necessity of my returning to the practice of law. In addition, I told him, it was my philosophy that public service is improved by periodic return to private life. A public official should feel free to do what he deems to be right and best, whether or not those actions will be most apt to maintain him in office. Because such independence sometimes requires unpopular actions, the official must be willing to risk losing his office and having to return to private lifeand that makes it necessary to have a private career to which one can return. I am also convinced that uninterrupted public office tends to lessen a persons objectivity and leads often to an unhealthy separation from the life, the thinking, and the needs of private citizens. Although I salute those who follow an uninterrupted public career, and acknowledge that continuing years of service often develop special expertise, I also think there is benefit to the public for at least some people to serve only on occasion, in special circumstances.

With Trygve Lie at the United Nations

I temporized by telling Trygve Lie that, in any event, he would need the approval of our government before we could consider the proffered position seriously. He responded that he had already obtained that approval from the secretary of state. He proceeded to make the position very challenging. He explained that while there was no such office, technically, as Under Secretary-General (only the several assistant secretaries-general, one of whom is an American), he would create the special circumstances that would result in the de facto position. He took me to the window of his office and pointed down to the official guest house on the grounds, a charming white residence surrounded by a picket fence. He said significantly, You and your family will live there. No other assistant secretary-general will have an official residence. Then he added that whenever he left the New York headquarters on various official missions over the world (and this occurred often) he would always designate me the acting secretary-general. Everyone will soon get the ideathat you are indeed the under secretary-general. I would have had no trouble turning down the administrative post of assistant secretary-generalbut the unique post he proposed to create was admittedly most tempting. In those years the U.N., by the exercise of its good offices, was often able to prevent war, maintain the peace, or terminate conflict in many places around the globe. The spectrum of challenge in the international field was unlimited. But acceptance, I was convinced, would have spelled the end of my professional career, which was my anchor of financial independence. With genuine regret, I reached the conclusion that for my own future freedom I had to decline and return to Louisville to reestablish myself as a lawyer.

This decision on the U.N. post was a turning point in my life. Had I accepted, I would probably have served in public positions the rest of my days. As it is, out of my more than fifty years at the bar, I have spent a total of some ten in public life, and the remaining forty or so in private life, in the practice of my profession and in various extracurricular civic activities. It is about the adventures of those ten public yearsthose periodic whistle stops in the public arenathat I now write.

Chapter 2

The Home Front

From my earliest recollection I have always felt the challenge of public life and the conviction that the most important activity of mankind is to participate in the betterment of each generationexpressed in the oath of every Athenian youth to leave his city better than he found it. Biography, especially of political leaders, was an early boyhood fascination for me. I had read with avid interest those biographies of public figures in Lords Beacon Lights of History. By the time I was nine or ten I had already decided I would like to be a lawyer, as the legal profession offered the combined advantages of an interesting career and relative freedom to participate in public life.