Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

THE POTAWATOMI INDIANS

BY

OTHO WINGER

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

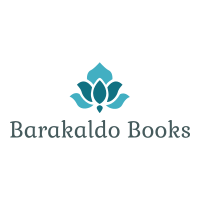

Chief Leopold Pokagon

Joe and Lou Ann

Starved Rock

Fort Dearborn and Environs

The Battle of Fort Dearborn and Environs

Looking North on Michigan Avenue

Potawatomi Agency Houses

Potawatomi Family

Chi-chi-pe Ou-ti-pe, Menominee Chapel

Monument to Menominee

Marker on the Site of Chi-chi-pe Ou-ti-pe

Land of the PotawatomiTrails and Villages

Big Potawatomi Springs

Reservations and Villages

Chief Menoquet

Site of Potawatomi Mills, Lake Manitou

Tippecanoe River at Chippewanung

Where the Michigan Road Crosses the Tippecanoe

Site of Fort St. Joseph

Monument of Chief White Pigeon

Potawatomi Girls in the Athens High School

The Potawatomi Church

Chief Metea

Chief Shabbona

Where the Sauk Trail Crossed the St. Joseph River

Path Leading to the Old Cemetery

Isaac and Christiana McCoy

Site of Carey Mission

Site of Pokagon Chapel

Simon Pokagon

Long Lake Catholic Chapel Near Dowagiac

Jewett Pokagon and Wife

Air View Potawatomi Inn

PREFACE

This book is one of the results of years of interest in, and study of, the American Indian. Former studies put in book form have been received with such favor that I have been encouraged to put out another volume. Former books have been about the Miami Indians. They were neighbors to the Potawatomi Indians and had much history in common. In the territory in which I do much work and travel, there are many places with Potawatomi names. Almost every county is rich in history and tradition about the red men who lived here but little more than a century ago. Much of this history and tradition is unknown to the present generation. To me it is not only interesting history but important as well.

At the close of the book is a bibliography of the main works I have read and from which I have gathered information. I am unable to list all the papers and books from which I have received impressions and information. I have visited most of the county libraries in this region and have read their pioneer histories and papers. I have received much help in the Indiana State Library and in the various libraries of Chicago. I have talked with many people both Indians and white men about these subjects. To all of these I owe my thanks. I owe special thanks to Alice M. Doner, Gletha Mae Noffsinger and Irene Winger for their help in preparing the manuscript; also to Inez Gochenour, Eugene Butler and Lorrell Eikenberry, for the maps and illustrations.

This book is sent forth with the hope that it will increase interest in local history and in the story of the Indians who preceded us and on whose lands we now live.

CHAPTER ITHE POTAWATOMI INDIANS AND THEIR EARLY HISTORY

The Pot-a-wat-o-mi Indians were a tribe of the great Algonquin race, whose tribes stretched from the Atlantic to the Mississippi and beyond. The Potawatomi and the Ottawa were closely related to the Chippewa who were the Ojibway of Longfellows Hiawatha. The three were probably one tribe in ancient days when, according to the legend of Longfellow, Hiawatha was their national hero.

Just when the Potawatomi left the parent family and become a separate tribe is not known. The usual explanation of the meaning of their name is people of the place of fire. They were often spoken of as fire builders with various explanations as to how this name applied to them. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that when this group decided to become a tribe, separate from the parent family, they decided to build a council fire for themselves. So the name was suggested from puttawa, blowing a fire, and mi, a nation; that is, a people able to build their own national fire and exercise the right of self-government. The council fire was a very important thing in the life of a tribe, for it was the center of their national decisions. Some say that the Potawatomi were jealous of their national council fire, and never allowed it to go out. If so, the name Put-ta-wa-mi is significant. The name has been variously spelled, but the most prominent authorities in recent years have used the more simple form, Pot-a-wat-o-mi, with the accent on the first and third syllables.

The original home of the Potawatomi was with or near, the parent tribe in the great lake region of northern Michigan, on the western shores of Lake Huron. From here they were driven west by the powerful Iroquois. They were met by early European explorers on the western shore of Lake Michigan, near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Again they were found at Sault Ste. Marie, in the peninsula of northern Michigan, where they were fleeing from the powerful Sioux who came from the west. The Potawatomi, like some other Algonquin tribes, were found in various places, where they were trying to escape the vengeance of one or the other of these two great tribes.

The Potawatomi themselves became known as of two divisions. Those who moved south from the forests of northern Wisconsin into the prairies of northern Illinois and western Indiana became known as Prairie Potawatomi, or Mascoutens. Those who remained in the forests of northern Wisconsin and Michigan became known as the Potawatomi of the Woods, or Forest Potawatomi. In language, traditions, and customs, the Forest Potawatomi retained a closer relationship with the Chippewa and Ottawa. The Prairie Potawatomi became the more important group and with them the early white men had important relationships.

By the close of the seventeenth century the Potawatomi had moved south from their northern homes into the Illinois country and around the southern end of Lake Michigan into southern Michigan. Already they were occupying lands formerly owned by the Illinois and Miami Indians. They were increasing in numbers and power.

In the French and Indian War the Potawatomi, like most of the tribes of the Northwest, took the side of the French. After the war, when the English had placed garrisons here and there, the Potawatomi joined Pontiac in his conspiracy to drive the English from the Indian lands. They were given the work of capturing Fort St. Joseph near the present Niles, Michigan. They did that with all savage cruelty, massacring eleven of the fifteen soldiers stationed there. They spared the lives of Captain Schlosser and three others whom they took to Detroit and exchanged for Potawatomi prisoners. After the fall of Fort St. Joseph these same Indians then hastened south on the old Indian trail to take part in the capture and massacre at Ft. Miami, now Fort Wayne, May 27, 1763.