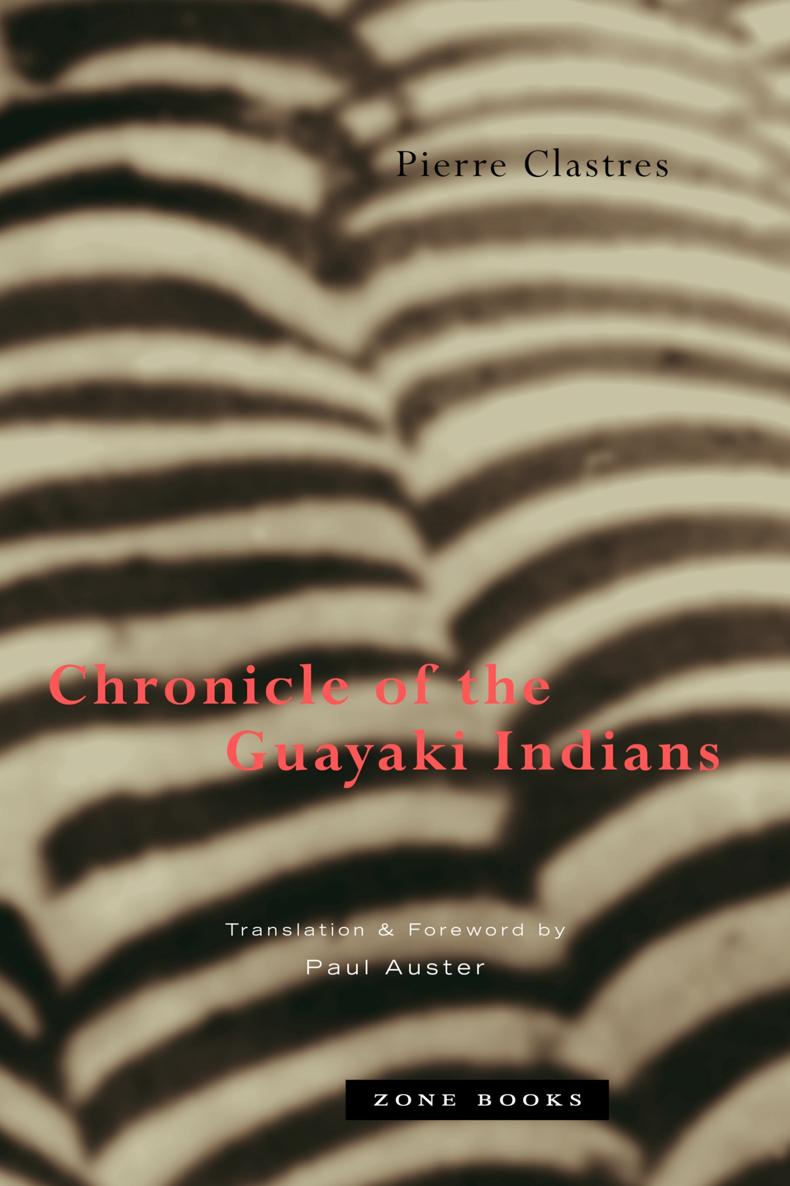

The publisher would like to thank the French Ministry of Culture for its assistance with this translation.

Translation 1998 Paul Auster

Translators Note 1998 Paul Auster

ZONE BOOKS

633 Vanderbilt Street

Brooklyn, NY 11218

All rights reserved.

First ebook edition 2021

ISBN 978-1-942130-59-8

eISBN 9781942130598

Version 1.0

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the Publisher.

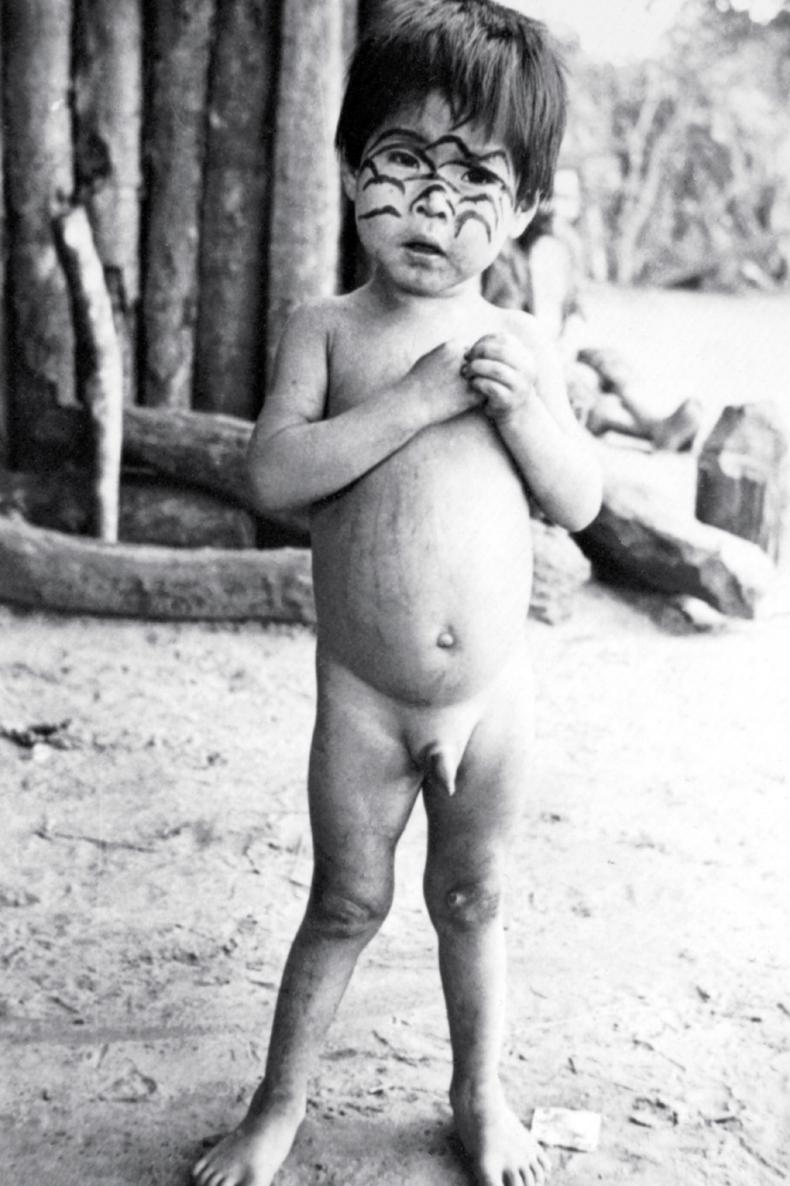

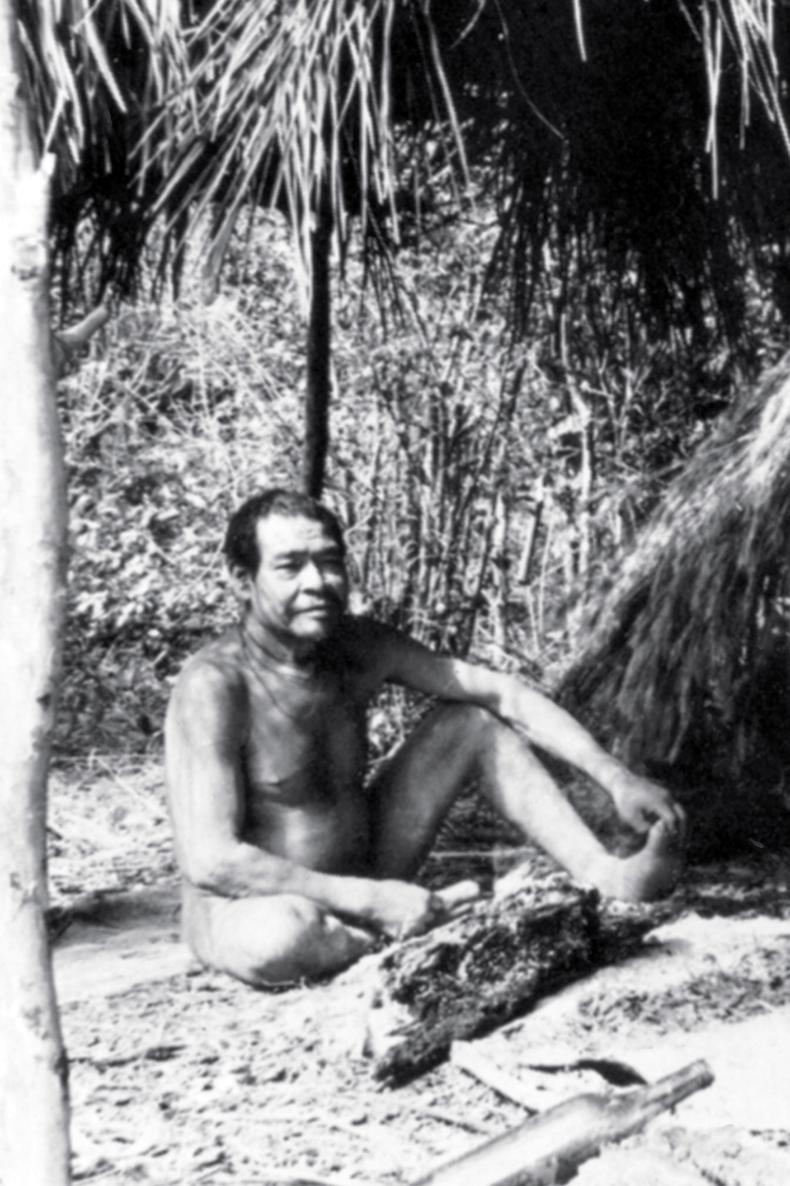

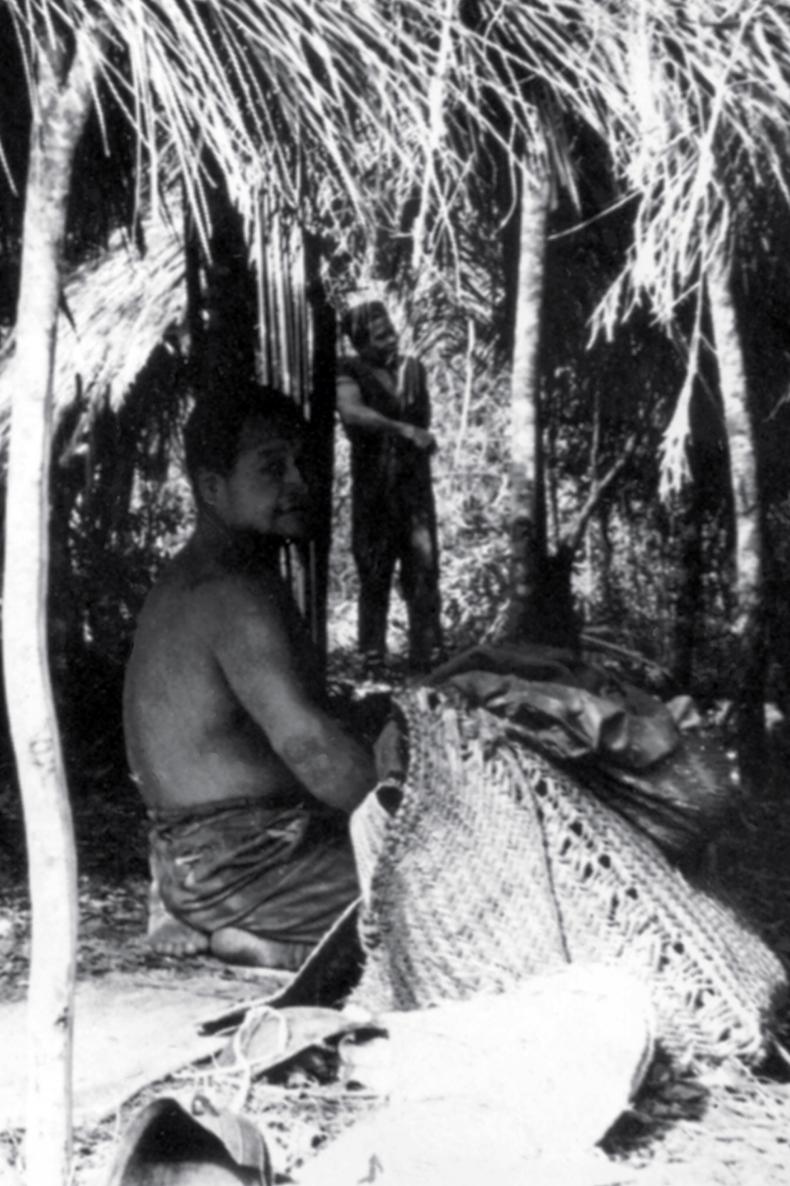

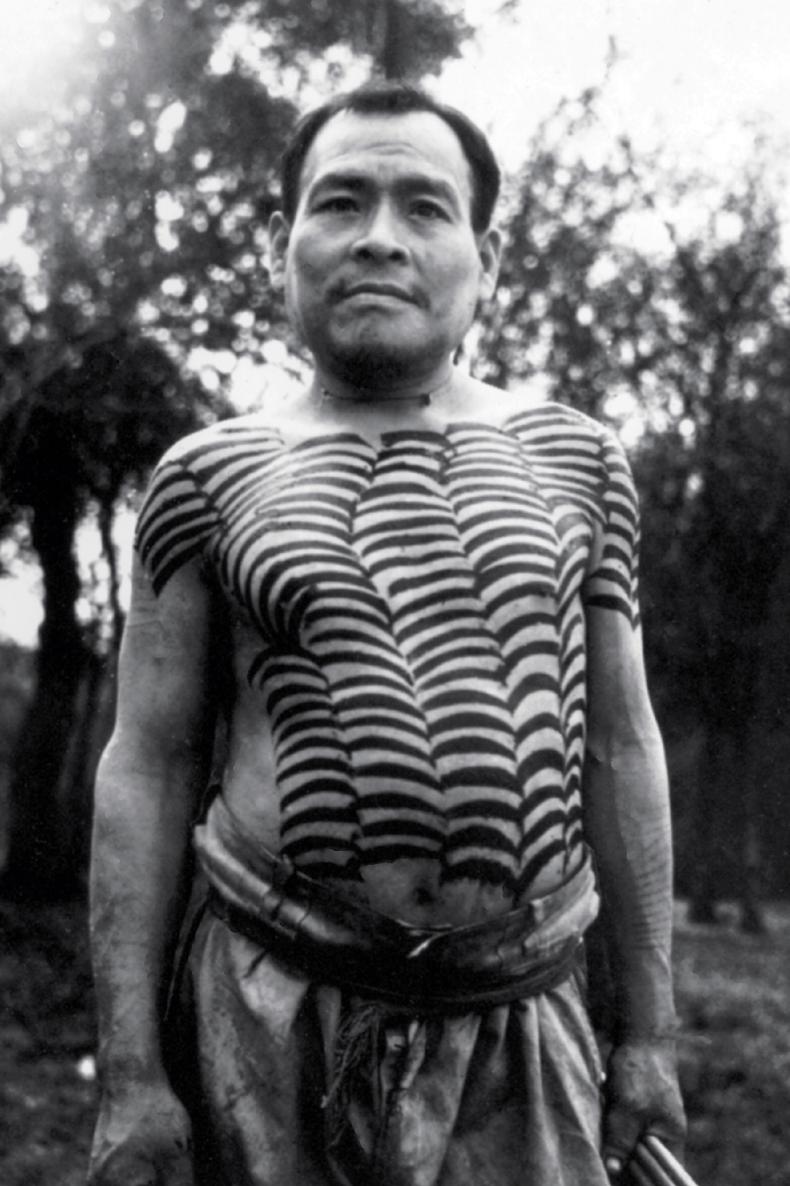

Originally published in France as Chronique des indiens Guayaki 1972 Librarie Plon. Drawings by Jean-Marc Chavy. Photographs by Pierre Clastres.

Distributed by Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey, and Woodstock, United Kingdom

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clastres, Pierre, 19341977

[Chronique des indiens Guayaki. English]

Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians / Pierre Clastres translated by Paul Auster.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-942299-78-6 (pbk.)

1. Guayaki Indians. I. Title.

F2679.2.G9C5513 1998

989.200498382 dc21

97-20623

Translators Note

This is one of the saddest stories I know. If not for a minor miracle that occurred twenty years after the fact, I doubt that I would have been able to summon the courage to tell it.

It begins in 1972. I was living in Paris at the time, and because of my friendship with the poet Jacques Dupin (whose work I had translated), I was a faithful reader of Lphmre, a literary magazine financed by the Galerie Maeght. Jacques was a member of the editorial board along with Yves Bonnefoy, Andr du Bouchet, Michel Leiris, and, until his death in 1970, Paul Celan. The magazine came out four times a year, and with a group like that responsible for its contents, the work published in Lphmre was always of the highest quality.

The twentieth and final issue appeared in the spring, and among the usual contributions from well-known poets and writers, there was an essay by an anthropologist named Pierre Clastres entitled De lUn sans le multiple [Of the one without the many]. Just seven pages long, it made an immediate and lasting impression on me. Not only was the piece intelligent, provocative, and tightly argued, it was beautifully written. Clastress prose seemed to combine a poets temperament with a philosophers depth of mind, and I was moved by its directness and humanity, its utter lack of pretension. On the strength of those seven pages, I realized that I had discovered a writer whose work I would be following for a long time to come.

When I asked Jacques who this person was, he explained that Clastres had studied with Claude Lvi-Strauss, was still under forty, and was considered to be the most promising member of the new generation of anthropologists in France. He had done his fieldwork in the jungles of South America, living among the most primitive Stone Age tribes in Paraguay and Venezuela, and a book about those experiences was about to be published. When Chronique des indiens Guayaki appeared a short time later, I went out and bought myself a copy.

It is, I believe, nearly impossible not to love this book. The care and patience with which it is written, the incisiveness of its observations, its humor, its intellectual rigor, its compassion all these qualities reinforce one another to make it an important, memorable work. The Chronicle is not some dry academic study of life among the savages, not some report from an alien world in which the reporter neglects to take his own presence into account. It is the true story of a mans experiences, and it asks nothing but the most essential questions: how is information communicated to an anthropologist, what kinds of transactions take place between one culture and another, under what circumstances might secrets be kept? In delineating this unknown civilization for us, Clastres writes with the cunning of a good novelist. His attention to detail is scrupulous and exacting; his ability to synthesize his thoughts into bold, coherent statements is often breathtaking. He is that rare scholar who does not hesitate to write in the first person, and the result is not just a portrait of the people he is studying, but a portrait of himself.

I moved back to New York in the summer of 1974, and for several years after that I tried to earn my living as a translator. It was a difficult struggle, and most of the time I was barely able to keep my head above water. Because I had to take whatever I could get, I often found myself accepting assignments to work on books that had little or no value. I wanted to translate good books, to be involved in projects that felt worthy, that would do more than just put bread on the table. Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians was at the top of my list, and again and again I proposed it to the various American publishers I worked for. After countless rejections, I finally found someone who was interested. I cant remember exactly when this was. Late 1975 or early 1976, I think, but I could be off by half a year or so. In any case, the publishing company was new, just getting off the ground, and all the preliminary indications looked good. Excellent editors, contracts for a number of outstanding books, a willingness to take risks. Not long before that, Clastres and I had begun exchanging letters, and when I wrote to tell him the news, he was just as thrilled as I was.

Translating the Chronicle was a thoroughly enjoyable experience for me, and after my labors were done, my attachment to the book was just as ardent as ever. I turned in the manuscript to the publisher, the translation was approved, and then, just when everything seemed to have been brought to a successful conclusion, the troubles started.

It seems that the publishing company was not as solvent as the world had been led to believe. Even worse, the publisher himself was a good deal less honest in his handling of money than he should have been. I know this for a fact because the money that was supposed to pay for my translation had been covered by a grant to the company by the CNRS (the French National Scientific Research Center), but when I asked for my money, the publisher hemmed and hawed and promised that I would have it in due course. The only explanation was that he had already spent the funds on something else.