An imprint of Ratna Sagar P. Ltd.

Virat Bhavan

Mukherjee Nagar Commercial Complex

Delhi 110 009

Offices at CHENNAI KOLKATA LUCKNOW

AGRA BANGALORE COIMBATORE DEHRADUN GUWAHATI HYDERABAD JAIPUR KANPUR KOCHI MADURAI MUMBAI PATNA

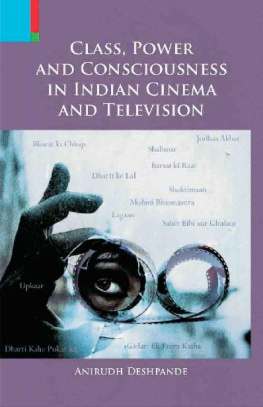

Anirudh Deshpande 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

First published 2009

Reprinted 2013

Published by Primus Books

Laser typeset by Sai Graphic Design

A.K. Road, Paharganj, New Delhi 110 055

Printed at Sanat Printers, Kundli, Haryana

This book is meant for educational and learning purposes. The author(s) of the book has/have taken all reasonable care to ensure that the contents of the book do not violate any existing copyright or other intellectual property rights of any person in any manner whatsoever. In the event the author(s) has/have been unable to track any source and if any copyright has been inadvertently infringed, please notify the publisher in writing for corrective action.

T HE FIVE chapters of this volume comprise an attempted critique of modern Indian visual narratives. They are based on the premise that since the early twentieth century the media in India has represented, in general, a changing consciousness peculiar to the Indian middle-class. However, the media, from the colonial to our post-colonial times, has also fashioned class consciousness in the very process of representing it. Therefore, it is only natural that significant parts of these chapters focus the readers attention on the Indian bourgeoisie. Not only does this author belong to the Indian middle-class but the context within which he has located modern Indian media is also culturally conditioned by Indian middle-class values and political perceptions. Many of the ideas which have silently, and sometimes openly, guided these chapters have emanated from casual conversations and involved discussions which I have had, and continue to have, with friends and accquaintances who come from solid bourgeois stock. To this author the Indian bourgeoisie, like the middle-classes elsewhere, appears culturally conservative and politically reactionary, despite its pretentions to the contrary. It is perhaps not necessary to add that this view does not square with the prevalent post-globalization perceptions of the Indian middle-class. I do not subscribe to the view according to which the great Indian middle-class is converting India into a happening modern place. I do not believe that the Indian bourgeoisie is modern in the enlightenment sense of the term. Nor is it capable of ushering in Western style modernity into the heterogeneous Indian social landscape. Self adulation is a typical bourgeois trait which the following chapters, hopefully, undermine. In sum, on the Indian middle-class and the Indian state I find my views closer to those evinced in the writings of people like Vijay Tendulkar, Praful Bidwai, Achin Vanaik and Kiran Nagarkar. Such views are generally at variance with those which are expressed regularly in newspaper columns written by the self-professed Indian liberals. In fact, and as the events of our times suggest, there is every reason to believe that the present and future of this country is unsafe in the hands of its ruling class. This volume is not divorced from these perceptions. On issues of power and consciousness I am inspired by the writings of Bertrand Russel and Noam Chomsky. On globalization I find Joseph Stiglitz relevant while the Marxism I prefer derives sustenance from the work of historians like E.P. Thompson.

The Indian middle-class and its historical self-consciousness, to begin my story, was produced by British colonialism. Since the early nineteenth century the British rulers of India tried their best to produce a class of Indians imbued with trappings of a modernity which was subservient to colonial interests. The results of this conscious policy as well as other elements produced by colonial rule in India turned out to be rather interesting. Impressed by the much valorized role of the bourgeois in European history, the Indian middle-class began gradually to consider itself the harbinger of modernity in India. Its leading intellectuals began to fashion a discourse, the essentials of which were borrowed from the bourgeois model of history popularized by the colonial ruling class. The bulk of the Indian bourgeoisie was produced by the unique interaction of British colonial rule and modern education with the traditional elite of Indian society. Liberal capitalist interpretations of the early modern enlightenment, as a vehicle of progress and development, became integral to the consciousness of this class in the very nineteenth century. To begin with, the national project of this middle-class was made problematic by the colonial conditions confronting it. According to this book, the national project spans the colonial, post-colonial and neo-colonial periods of Indian history.

The history of Indian cinema tells us how the bourgeois nation has been historicized, narrativized and defined differently in varying contexts. From anti-colonialism, followed by nation building and planned development, to the contemporary years of a collaborationist globalization, the Indian bourgeoisie has experienced an interesting journey. The majority of Indian media is capitalist-owned and bourgeois-controlled. With few exceptions it represents and justifies these episodic transitions in the name of liberalism, progress and growth. However, even as the political emphasis of the ideal bourgeois nation-state changed in India from the early twentieth century to the late nineteen nineties, the social engineering preferred by the Indian bourgeoisie has displayed a remarkable consistency. This peculiar consistency, central to the maintenance of patriarchal and caste continuity in the face of historical change, is exposed and attacked by the post-modernist. Critics of modernity view modernization as a euphemism for the spread of bourgeois hegemony in general. This view has some merit because modernization does involve the subjugation of subaltern groups and expropriation of their resources, including labour, by those who wield power in the name of ideological singularities like civilization, religion, nation, development, market or even democracy. The critique of modernity rejects the idea of historical inevitability, supports human volition in history, and tries to undermine master narratives, according to which human progress and development are necessarily implied in historical change and technological growth. But criticizing modernity does not mean uncritically accepting tradition or whatever is understood by the term. In recent years it has increasingly been noticed that many traditions are quite recent and were probably invented by the knowledge systems of both the colonial and post-colonial worlds. In sum, a balanced critique of historical knowledge which translates into cinematic representation in India, a goal which inspires this volume questions the apotheosis of modernization and glorification of tradition projected simultaneously in the ideological universe of Hindi cinema and television. The narrative of the nation-state constructed by commercial Hindi cinema is a result of the Indian bourgeois attempt to combine the universal material values of Western enlightenment with the so-called spiritual and moral values of Indian tradition. This Indianization of the modern nation-state is ultimately achieved by resolving disconcerting contradictions like class, gender, and religious, ethnic and caste discrimination in favour of caste Hindu patriarchy. In the first half of the twentieth century, Hindi cinema evolved as an efficient medium of bourgeois hegemony in India. In the interest of the Indian ruling class, Hindi cinema has carefully constructed an impressive historical narrative of the Indian nation by either excluding or marginalizing several social groups and issues in its representation of Indian society.

![Madhav Deshpande - Critical Studies in Indian Grammarians I: The Theory of Homogeneity [Sāvarṇya]](/uploads/posts/book/255206/thumbs/madhav-deshpande-critical-studies-in-indian.jpg)

![Anirudh Prabhu [Anirudh Prabhu] - Beginning CSS Preprocessors: With SASS, Compass.js and Less.js](/uploads/posts/book/119148/thumbs/anirudh-prabhu-anirudh-prabhu-beginning-css.jpg)