Inequality

Inequality

A Genetic History

Carles Lalueza-Fox

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lalueza i Fox, Carles, 1965- author.

Title: Inequality : a genetic history / Carles Lalueza-Fox.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021011599 | ISBN 9780262046787 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Social statusHealth aspects. | EqualityHealth aspects. | Human geneticsSocial aspects. | Human population genetics. | Human evolution. | Sociobiology.

Classification: LCC RA418.5.S63 .L358 2022 | DDC 362.84dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021011599

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

Contents

History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake

James Joyce, Ulysses

When I was a child, there were many history books at home that my father had boughtbut that sadly, he never had the time to read. Even the street where we lived, in the Gothic Quarter of Barcelona, was made of history, with most of its buildings dating back to the Middle Ages. Ancient history was a matter of conquerors, dramatic quotes, bloody battles, and deaths. But the anonymous folks, the common peoplethe bulk of the populationwere never even mentioned. Although my career gravitated toward evolutionary biology, history always remained my main intellectual interest. (One might argue, of course, that the two disciplines, along with astronomy, share one element: the time dimension.)

After years of working on Neanderthal genetics, I grasped that the novel DNA sequencing technologies could help us explore the recent human past using a new, multidisciplinary approach that integrated genetics, archaeology, anthropology, and even linguistics. In 2014, I led the retrieval of the first European forager genome from an eight-thousand-year-old skeleton and the next year the first early farmer genome from the Mediterranean.

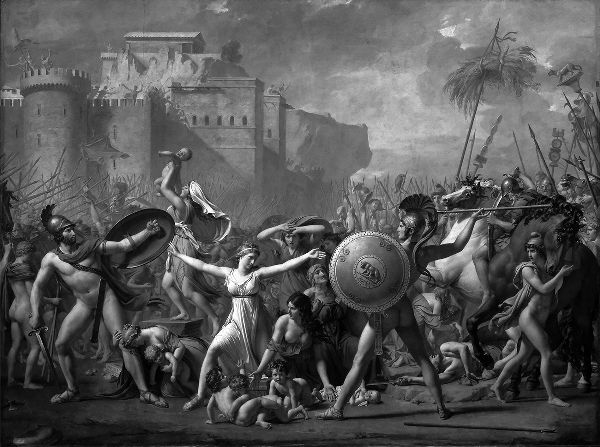

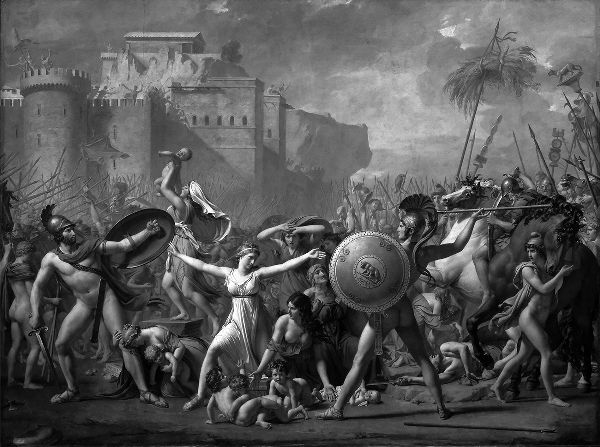

One day, in a casual conversation about my work, my wife said that I tended to look into the past through a mans eyes and that the history of humanityin fact a long road of suffering and discrimination, still going on for manyincluded women, no less than half the worlds population. And she was right; though women are largely ignored in the old history books, they crucially bear each new generation of humankind. Just think how differently a legendary tale like the kidnappingand by modern standards, subsequent rapeof Sabine women by Romulus and his companions in the early history of Rome, abundantly represented in art in a rather heroic manner, might be told from the female rather than the usual male perspective.

I realized that directly or indirectly, the new genetic studies were in fact revealing numerous layers of inequality in past societies, from the potential gender biases that we were unearthing in those migrations to the social structures implemented to maintain such inequalities as well as correlating wealth and social status with sex, kinship, and ancestry in cemeteries. Powerful men of the past could have more offspring, from different women, than contemporaneous men that were left with no childrenor with children who had less chance to survive.

Figure 0.1

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painted by Jacques-Louis David (17481825) in 1799 (on display at the Louvre Museum, Paris). This episode, recounted by Livy and Plutarch, was frequently depicted since the Renaissance as an inspiring example of ancient Roman heroism.

Some recent studies set out to analyze the genetic composition of African slaves, and in conjunction with genomic analysis from recently admixed modern populationsnotably those of the Americasit was possible to reconstruct unequal reproductive patterns. Again, if we shift our point of view, certain anecdotes of the past, such as that George Washingtons dentures were possibly made from teeth pulled out of the mouths of Black slaves, are all the more shocking and quite understandably have generated a broad range of reactions.

Crucially, such patterns of inequality all left genetic marks that can be recognized in the genomes of ancient and modern human populations. Whenever I looked at a new genetic study, I saw new evidence of inequality and discrimination in different times and periods, and I decided to write this book to speak for those past figures who suffered the consequences. A number of baffling ideas came out of these observations. To mention but a few: those who sustained inequality in the past and had more offspring are more likely to be among our genetic ancestors, and if wealthy men could mate with multiple women and this was a prevalent pattern, then clearly women have contributed more than men to modern human genetic diversity.

Philosopher Walter Benjamin was right when he said, It is a more arduous task to honor the memory of anonymous beings than that of famous persons. But with genetic data, this task is now possible to achieve. The main observation is that historythe history of heroic acts, wars, and conquestshas indeed been a tale of inequality that modeled the genomes of humankind.

That said, inequality is not just a curiosity of the past. When I started this book, I predicted that inequality would differentially influence mortality in the current COVID-19 pandemic, and a few weeks later, my hunch was confirmed. Inequality is entangled in our genomes, but it also casts a long shadow over the future of society. Well need to decide sooner than later how we want to face it.

Inequality was the unalterable law of human life.

George Orwell, 1984

We live in an age of growing inequality, and to such an extent that the concept has become a social concern. In Google searches, the word inequality has been on the rise, especially since the year 2004. In a database of millions of books published since 1800 on Google Ngrams, the frequency of the word inequality remains almost undetected from 1800 to 1960; thereupon it surges continuously. In 2013, President Barack Obama said that income inequality is the defining challenge of our time, and one year later, Pope Francis stated, Inequality is the root of social evil. According to Oxfams 2020 report, the 2,153 richest people on the planet have amassed more wealth than 60 percent of humankind, and according to Swiss bank UBS, the global billionaire wealth climbed to a new record of $10.2 trillion during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, between April and July 2020.

Parallel to a general public interest in present-day disparity in incomes there has been an academic interest in understanding the causes and consequences of its increase. In this context, the success of the 2014 book by the French economist Thomas Piketty,

Next page