THE GREAT

LEVELER

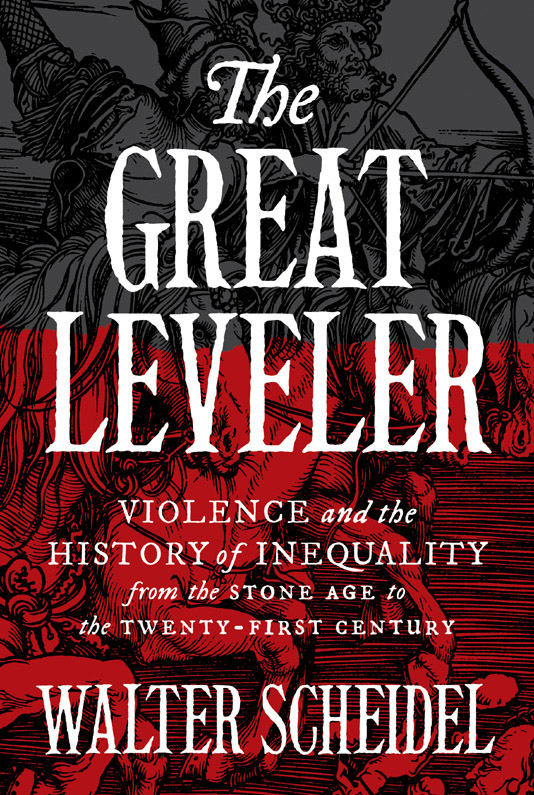

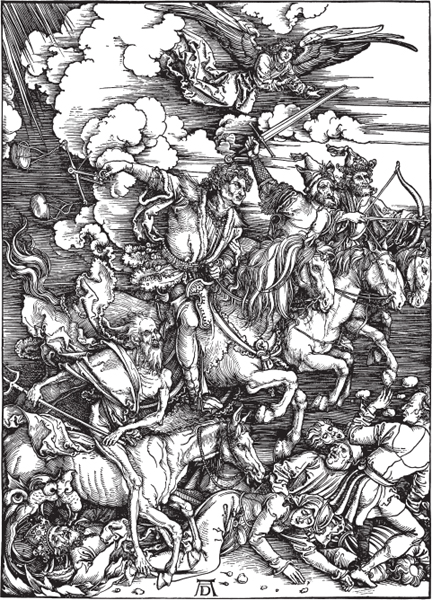

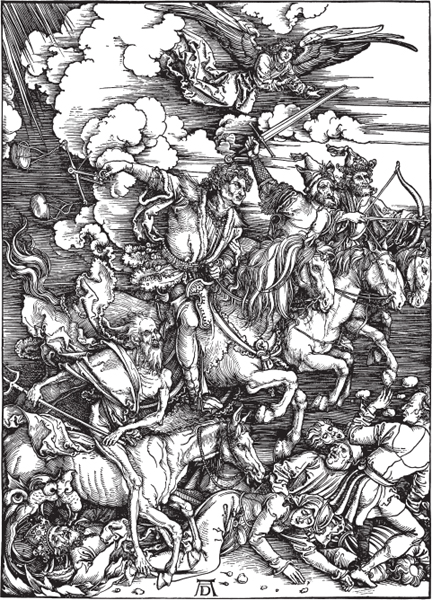

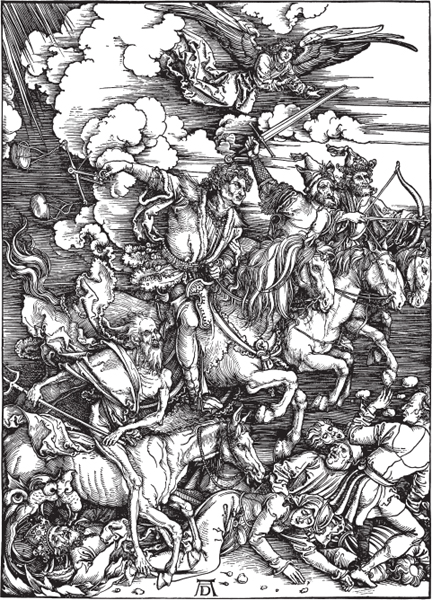

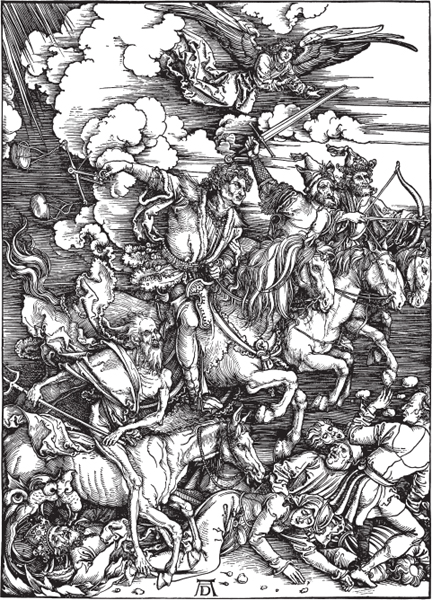

Albrecht Drer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, from The Apocalypse, 14971498. Woodcut, 15 11 in. (38.7 27.9 cm).

THE GREAT

LEVELER

VIOLENCE AND THE HISTORY OF

INEQUALITY

FROM THE STONE AGE TO THE

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

WALTER SCHEIDEL

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Cover art: Albrecht Drer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, from The Apocalypse, 14971498.

Woodcut, 15 11 in. (38.7 27.9 cm).

All Rights Reserved

First paperback printing, 2018

Paper ISBN 978-0-691-18325-1

Cloth ISBN 978-0-691-16502-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953046

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

For My Mother

So distribution should undo excess,

And each man have enough.

Shakespeare, King Lear

Get rid of the rich and you will find no poor.

De Divitiis

How often does God find cures for us worse than our perils!

Seneca, Medea

CONTENTS

xi

xv

FIGURES

TABLES

The gap between the haves and the have-nots has alternately grown and shrunk throughout the course of human civilization. Economic inequality may only recently have returned to great prominence in popular discourse, but its history runs deep. My book seeks to track and explain this history in the very long run.

One of the first to draw my attention to this very long run was Branko Milanovic, a world expert on inequality who in his own research has reached all the way back to antiquity. If there were more economists like him, more historians would be listening. About a decade ago, Steve Friesen made me think harder about ancient income distributions, and Emmanuel Saez further piqued my interest in inequality during a shared year at Stanfords Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences.

My perspective and argument have been inspired in no small measure by Thomas Pikettys work. For several years before his provocative book on capital in the twenty-first century introduced his ideas to a wider audience, I had read his work and pondered its relevance beyond the last couple of centuries (also known as the short term to an ancient historian such as myself). The appearance of his magnum opus provided much-needed impetus for me to move from mere contemplation to the writing of my own study. His trailblazing has been much appreciated.

Paul Seabrights invitation to deliver a distinguished lecture at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Toulouse in December 2013 prompted me to fashion my disorganized thoughts on this topic into a more coherent argument and encouraged me to go ahead with this book project. During a second round of early discussion at the Santa Fe Institute, Sam Bowles proved a fierce but friendly critic, and Suresh Naidu provided helpful input.

When my colleague Ken Scheve asked me to organize a conference on behalf of Stanfords Europe Center, I seized the opportunity to gather a group of experts from different disciplines to discuss the evolution of material inequality in the long run of history. Our meeting in Vienna in September 2015 was both enjoyable and educational: my thanks go to my local co-organizers, Bernhard Palme and Peer Vries, as well as to Ken Scheve and August Reinisch for their financial support.

I further benefited from feedback at presentations at the Evergreen State College, the Universities of Copenhagen and Lund, and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. I am grateful to the organizers of these events: Ulrike Krotscheck, Peter Bang, Carl Hampus Lyttkens, Liu Jinyu, and Hu Yujuan.

David Christian, Joy Connolly, Peter Garnsey, Robert Gordon, Philip Hoffman, Branko Milanovic, Joel Mokyr, Reviel Netz, evket Pamuk, David Stasavage, and Peter Turchin very kindly read and commented on the whole manuscript. Kyle Harper, William Harris, Geoffrey Kron, Peter Lindert, Josh Ober, and Thomas Piketty also read parts of the book. A group of historians at the Saxo Institute in Copenhagen met to discuss my manuscript, and I am particularly grateful to Gunner Lind and Jan Pedersen for their extensive input. I received valuable expert advice on specific sections and questions from Anne Austin, Kara Cooney, Steve Haber, Marilyn Masson, Mike Smith, and Gavin Wright. It is entirely my own fault that I have not been as receptive to their comments as I surely ought to have been.

I am extremely grateful to a number of colleagues who generously shared their unpublished work with me: Guido Alfani, Kyle Harper, Michael Jursa, Geoffrey Kron, Branko Milanovic, Ian Morris, Henrik Mouritsen, Josh Ober, Peter Lindert, Bernhard Palme, evket Pamuk, Mark Pyzyk, Ken Scheve, David Stasavage, Peter Turchin, and Jeffrey Williamson. Brandon Dupont and Joshua Rosenbloom very helpfully generated and shared statistics on wealth distribution in the United States during the Civil War period. Leonardo Gasparini, Branko Milanovic, evket Pamuk, Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Ken Scheve, Mikael Stenkula, Rob Stephan, and Klaus Wlde kindly sent me data files. Stanford economics major Andrew Granato provided valuable research assistance.

I completed this project during a Stanford Humanities and Arts Enhanced Sabbatical Fellowship granted for the academic year of 2015/2016: my thanks go to my deans, Debra Satz and Richard Saller, for their support in this matter (in addition to many others). This sabbatical allowed me to spend the spring of 2016 as a visitor at the Saxo Institute of the University of Copenhagen when I was putting the finishing touches on my manuscript. I am grateful to my Danish colleagues for their warm hospitalityand above all to my good friend and serial collaborator Peter Bang. I also owe a somewhat awkward word of thanks to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for awarding me a fellowship to pursue this project. Having somehow managed to finish this book before I had a chance to take up this fellowship, I will be sure to make the most of it in my future endeavors.

As my project approached completion, Joel Mokyr kindly offered to include this title in his series and helped shepherd it through the review process. I have greatly appreciated his support and judicious comments. Rob Tempio has been a splendid instigator and editor, a true book lover and authors advocate. I am also in his debt for his having suggested the main title of this book. His colleague Eric Crahan granted me timely access to the page proofs of two related Princeton books. Further thanks are due to Jenny Wolkowicki, Carol McGillivray, and Jonathan Harrison for having ensured an exceptionally smooth and swift production process, and to Chris Ferrante for his striking cover design.