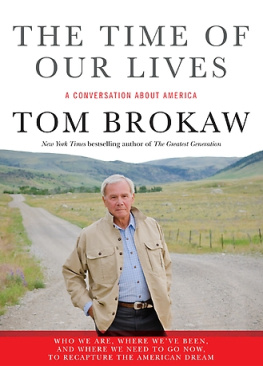

Copyright 2011 by Tom Brokaw

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Text permissions and photo credits can be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brokaw, Tom.

The time of our lives / Tom Brokaw.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-679-64392-0

1. United StatesSocial conditions1980 2. United StatesPolitics and

government1989 3. Social problemsUnited States. 4. National characteristics,

American. 5. Brokaw, Tom. 6. Television news anchorsUnited StatesBiography.

7. Television journalistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

E839.B69 2011

973.927dc23 2011022825

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: The Boland Design Company

Jacket photograph: Audrey Hall

v3.1_r1

PREFACE

W hat happened to the America I thought I knew? Have we simply wandered off course, but only temporarily? Or have we allowed ourselves to be so divided that were easy prey for hijackers who could steer us onto a path to a crash landing?

These were not questions I was asking in August 1962, when I was a newlywed and a rookie journalist. America was investing in a new generation of leadership and promise. John F. Kennedy was in the White House. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was on the march in the South. Astronauts with the right stuff pointed their aspirations toward the heavens. Women were stepping out from behind their aprons and questioning their assigned roles. Young artists were giving new voice to music, film, and literature.

I couldnt wait to be a part of it all.

A half century later it is a much different world, and I am a weathered survivor of the rearranged American landscape, a familiar territory for me in my personal and professional life. Wherever I go I am asked, What has happened to us? Have we lost our way?

One often repeated question is the most troubling of all, because it challenges an American belief so fundamental it might as well be carved in stone on a Washington monument: Will our children and grandchildren have better lives than us?

Is that essential part of the American Dream disappearing? There are no simple, reassuring answers, and as a citizen, father, and grandfather, I am not immune to the worries that prompt the question. I believe it is time for an American conversation about legacy and destiny.

I am not a sociologist or a psychologist. I am a journalist, an observer, and a synthesizera man who has explored a lot of the world and been a witness to recent history. I have seen what enlightened leadership can accomplish, whether it is on a family, community, national, or world level. Ive also been astonished by our capacity to make the same mistakes in one form or another again and again.

I have made my own share of mistakes, as we all have. Theyve yet to invent a GPS system for the best road to a secure and worthwhile future, but I do have some thoughts, original and inspired by others, for our journey into the heart of a new century. To begin, isnt it time to reflect on where we have been and how we are going to move forward together, and to do it with more listening and less shouting?

There is a good deal of debate these days about American exceptionalismabout who believes in it and who may have doubts. I have no doubts. But I also believe that the unique character of America is very much like my definition of patriotism: Love your country but always believe it can be improved.

That was the unspoken way I was raised by a family of patriots and mentors who represented a broad spectrum of political and cultural notions but shared a common belief in the American Dream and a determination to constantly renew Americas promise. Those indelible lessons from family and friends are still with me, and I hope you will find them familiar and worth renewing as they play out across the chapters that follow.

What I know for sure is that many feel America is adrift, and the time to build the future is now. We will be judged not simply by the cacophony of those on the left and right with access to a cable system or a blog but rather by the tangible legacy we leave behind.

This immigrant nationthis destination for those looking for economic opportunity, political freedom, and the realization of dreamshas confronted great trials in the past and prevailed. We can draw on those experiences and find new ways to address the challenges that await us now.

As I learned in the first decade of this new century, there are daring new ideas being tested in the laboratories of everyday life by bold and unconventional thinkers and doers. Youll hear their voices and learn their ideas in the pages that follow.

Academics tell us that centuries and decades are imperfect ways to measure the long curve of history. Perhaps, but for me every decade of my life, beginning with the forties, had a bold punctuation mark, so I had more than a little curiosity about what a new century might mean to us. The defining events of the first sixty years of my life were about to recede. What should we all expect next?

What follows are the observations, hopes, memories, and suggestions of a child of the twentieth century who had big dreams fulfilled beyond his boyhood fantasies. I am now a man of the twenty-first century, with some observations on how we might realize the great promise of a future that would benefit us all.

It was a New Years Eve unlike any other in my lifetime, and possibly yours.

On December 31, 1999, I stood on the top-floor terrace of the Renaissance Hotel, high above Times Square in New York City, looking down on the revelers jammed onto every square millimeter of sidewalk, curb, gutter, and streetan estimated two million who were giddily anticipating the beginning of a new century and a new millennium. We were part of a vast global gathering witnessing the turn of the clock from the momentous events of the twentieth centurywhat had been called the American centuryto the unknown events of a new calendar. There was a rolling wave of euphoria about the moment and apprehension about the unknown as the clock struck midnight around the world.

I was fifty-nine years old, a long way from my heartland roots, immersed in journalism, successful in my marriage and professional life, and a relatively new grandfather. I had reported on most of the major events of the previous four decades, from the triumphs, tragedies, and turmoil of the sixties in America through the resignation of a U.S. president, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the emergence of China as a political and economic force, wars in the Middle East and Central America, the birth of twenty-four-hour cable news, the still-evolving and transformative effect of cyberspace, and, at the time, a cheerful celebration of prosperity in ever more layers of American life.

While I tried to offer our audience some perspective on what this new, twenty-first century might bring, it was, in retrospect, a modest effort.

My friend and competitor Peter Jennings was across the way, anchoring an impressive and much more ambitious ABC News production on the turn of the century, as he demonstrated one of the marvels of our new age: communication by satellite and via Internet, which allowed him to instantly call up colleagues in China, Australia, Africa, and elsewhere, and bring the global party to his glassy studio in midtown Manhattan.