CONTENTS

For Mother

Acknowledgments

Over the years, as Ive shared stories of my South Dakota boyhood and family history, friends have often said, When are you going to write that in a book?, an idea I have successfully resisted until now. I worried that such a book could be seen as simply an exercise in vanity, rather than as what I hoped it would be, an attempt to document the manner in which I was raised in the America of the postWorld War II years. I wanted to get beyond an anchormans inflated sense of self-importance (an oxymoron?) and express my gratitude to the people who raised me, and to the character of life in the American heartland from which I have drawn so much. In any case, this is a book about my life until the age of twenty-two, when I left South Dakota.

One of the perils of embarking on such a book is that the prism through which you look back on your own life gives off a certain rosy tint. I have tried to avoid that, but it is also true that I grew up as a congenital optimist at a time when everything seemed possible in America, especially for a white male, and among people accustomed to difficult challenges, hard work, and productive results. I am also aware that I happened to be born in the right place at the right time, and to the right set of parents, who did not limit my dreams of a different kind of life.

I am deeply grateful for the assistance Ive received along the way, especially from my family, beginning with my mother, Jean Brokaw, and my wife, Meredith. They have been, as always, insightful and sensible in their comments and encouragement. Meredith and my daughters, Jennifer, Andrea and Sarah, provided invaluable observations as well.

I am also extremely grateful for the long and detailed history of the Brokaw family provided by the genealogists at the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City. It is a true treasure for our family.

Sarah Hodder and Phil Napoli were tireless and resourceful in their pursuit of the factual history of the Great Plains, the small towns where I lived and the time about which I wrote. Sarah, particularly, became an expert on turn-of-the-century development in northern South Dakota, dam construction on the Missouri River, and the social and political evolution of my hometown.

At NBC, I could always count on the energetic, efficient, and good-humored assistance of Sara Perkowski and Meaghan Rady. They have been peerless in their ability to organize and manage the NBC News part of my life when I was in a time-consuming phase of the book.

At Random House, Benjamin Dreyer, Richard Elman, Jolanta Benal, and Frankie Jones were indispensable and patient as they helped convert the manuscript into book form. Thank you all.

Carole Lowenstein and Daniel Rembert deserve special thanks for framing my words with photos and mementos going back a century.

What can I say about Kate Medina, my editor at Random House? This is our fourth book together, and there would have been none without her. In her cool, elegant way she gives me the courage to start and the advice that makes it possible to keep going. Kate plants good ideas and uproots bad ones, constantly tending the landscape of our common turf, always nudging me to higher ground.

Her assistant, Jessica Kirshner, was the master of logistics and the calm, friendly stalwart who deftly handled all of the incoming calls, photos, queries, and manuscripts. Whatever else happens in the world, Jessica, well always have our e-mail.

When I was in the final stages of my first book, The Greatest Generation, I asked two friends, Kurt Andersen and Frank Gannon, to read it. They were so generous with their time and so astute in their observations that Ive taken advantage of them again. Their comments on content, style, and theme were immeasurably helpful. Thank you, gentlemen.

Having said that, whatever mistakes, slights, oversights, and overstatements are contained herein, I am responsible. Because of the particular nature of this book, I did rely a great deal on personal memory, and although I pride myself on recall, I know that others may remember events in other ways.

I greatly regret that I couldnt mention by name everyone who was important to me as I was growing up. There were so many peoplefrom pals, girlfriends, and role models to teachers and friends of my parents. I am indebted to you all.

When I sent this book to my mother for her comments and corrections, she wrote back to say, In some parts your ego is showing, but mostly its fine. Forty years after I left home for the last time, she still has my number.

CHAPTER 1

A Long Way from Home

IN 1962, I PUT MY HOME STATE OF SOUTH DAKOTA IN A rearview mirror and drove away. I was uncertain of my final destination but determined to get well beyond the slow rhythms of life in the small towns and rural culture of the Great Plains. I thought that the influences of the people, the land, and the time during my first twenty-two years of life were part of the past. But gradually I came to know how much they meant to my future, and so I have returned often as part of a long pilgrimage of renewal.

When I do return, my wardrobe and home address are New York, my job is high-profile, and my bank account is secure, but when I enter a South Dakota caf or stop for gas, I am just someone who grew up around here, left a while back, and never really answers when hes asked, When you gonna move back home? I am caught in that place all too familiar to small-state natives who have moved on to a rewarding life in larger arenas: I dont want to move back, but in a way I never want to leave. I am nourished by every visit.

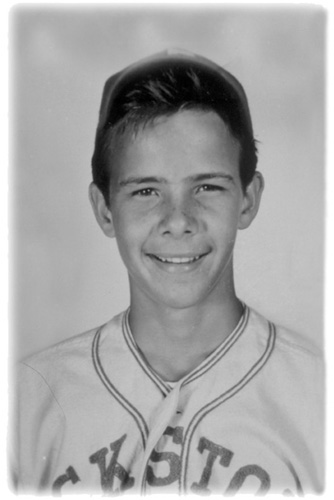

Dad and me during the summer of 1943.

On those trips back to the Great Plains I always try to imagine the land before it was touched by rails and plows, fences and roads. I can still drive off the pavement of South Dakota highways, find a slight elevation in the prairie flatness, and look to a distant horizon, across untilled grassland, and with no barbed wire or telephone poles or dwellings to break the plane of earth and sky. It is at once majestic and intimidating. More than a century after the first white settlers began to arrive, the old Dakota Territory remains a place where nature rules.

On a still, hot late-summer day, after a wet spring in the northern plains of South Dakota, the rich golden fields of wheat and barley, the deep green landscapes of corn and alfalfa surrounding the neat white farmhouses framed by red barns and rows of sheltering trees, give a glow of goodness and prosperity. It is hard to remember this was once a place of despair brought on by a cruel combination of nature and economic forces at their most terrifying.

This was a bleak and hostile land in the Dirty Thirties.

Families struggled against drought, grasshoppers, collapsed markets, and fear. Billowing clouds of topsoil, lifted off the land by fierce winds, reduced the sun to a faint orb; in April 1934, traces of Great Plains soil were found as far east as Washington, D.C. One report said the dust storm was so bad it left a film on President Franklin D. Roosevelts Oval Office desk.

Next page