To the memory of those

who didnt return

CONTENTS

Preceeding Photographs

AN

ALBUM

OF

MEMORIES

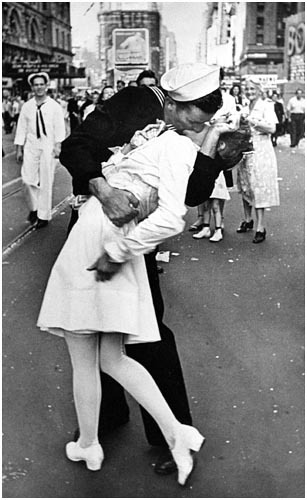

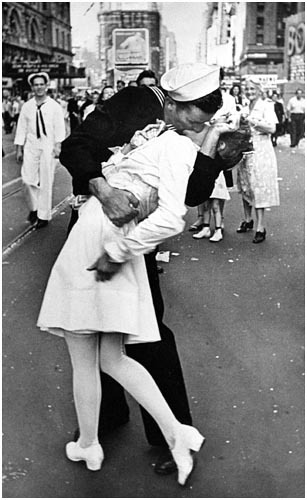

Celebrating the victory over Japan with a jubilant kiss in Times Square, August 14, 1945.

(Alfred Eisenstaedt/TimePix)

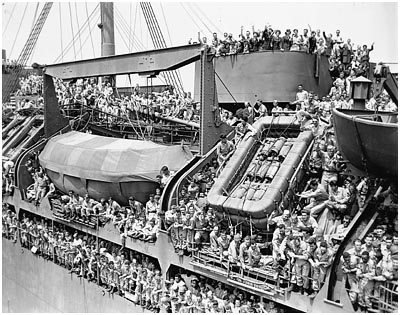

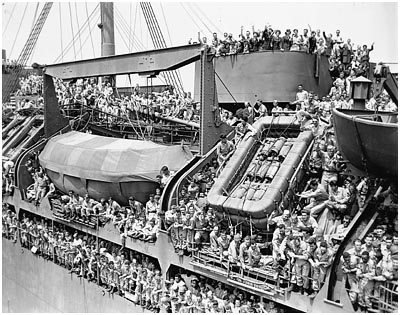

Army troops packed aboard the USS Gen. Harry Taylor as it docks in New York City on August 18, 1945. The transport ship was on its way to the Pacific front from Marseille, France, on August 7 when news of the Japanese surrender diverted it back home.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Private Samuel M. Cawthon, from Tyler, Texas, writes a letter home from his pup tent in Italy.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Bob Barrigan, a fellow sailor, and several Marines witness the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack from atop the Naval Operations building, approximately 11:00 A.M. , December 7, 1941. We were fully expecting an invasion and were sent to the rooftop with rifles. One sailor did not know how to load his and had to ask me for help.

(U.S. Navy Historical Center photo)

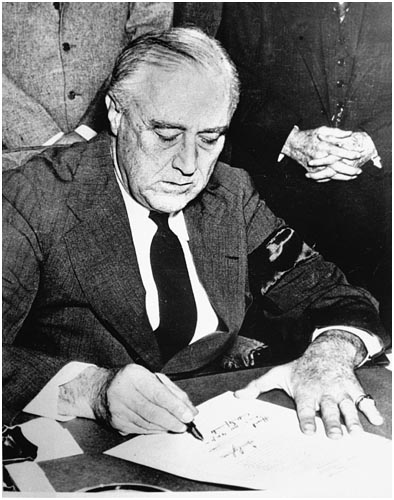

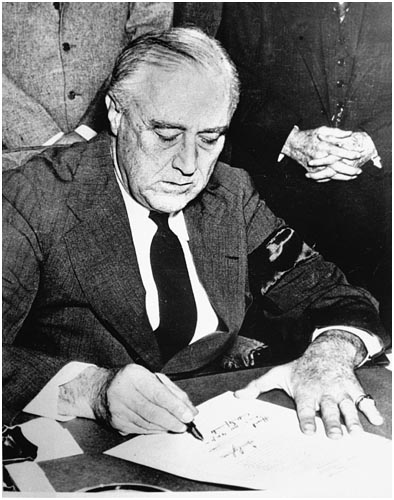

Wearing a black armband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs a declaration of war against Japan, a day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

(TimePix)

FOREWORD

For the past three years I have been immersed in the stories of what I call the Greatest Generation, those American men and women who came of age in the Great Depression, served at home and abroad during World War II, and then built the nation we have today. In two books, The Greatest Generation and The Greatest Generation Speaks, I documented their stories of bravery and sacrifice, achievement and humility, loyalty and service.

The reaction to these books has been deeply gratifying. Members of that generation, characteristically, are modest and yet quietly proud of what they have achieved individually and collectively, and proud also to have had their accomplishments recognized at this stage of their lives. In turn, their children and grandchildren tell me that they are reexamining their own lives and values, measuring them against the legacy of their parents and grandparents. It is a kind of symbiotic effect in which the generations, by interacting, are giving new meaning to their lives.

It was a common trait of the Greatest Generation not to discuss the difficult times and how they shaped their lives, but now, in their twilight years, more and more members of that remarkable group of men and women are determined to share their experiences.

Frankly, when the second book was finished, I thought we had exhausted the supply of fresh material, but the stories keep coming in, describing history as it was lived by ordinary peopleon D-Day, on Bataan, during the Battle of Midway, and so on. I have come to realize that there are still so many stories to be told, so many lessons to be learned from even the briefest recollections of that time of deprivation and war, heroism and belief, uncertainty and peril.

So this album of memories is a way of celebrating more of those lives and preserving their memories and stories. It is designed to complement the earlier books and also the new World War II memorial in Washington, D.C. Part of the proceeds from the sale of An Album of Memories will be dedicated to the work of the memorial.

Again, I am deeply indebted to the men and women whose stories you will find here, and to their children and friends who offered their reflections as well.

I am, as always, especially grateful for the inexhaustible and invaluable assistance of Elizabeth Bowyer and Philip Napoli, Ph.D. This book would not have been possible without them.

I am grateful too for the assistance of James Danly.

At NBC, Diana Rubin, Meaghan Rady, Sara Perkowski, and Eric Wishnie were tireless and extremely well organized in their dedication to this project.

Once again, Kate Medina, my friend and editor at Random House, was the company commander, a cool and insightful mentor and motivator.

Others at Random House without whom this book could not have been accomplished include Frankie Jones, Benjamin Dreyer, Carole Lowenstein, Andy Carpenter, Richard Elman, Susan Brown, and Maria Massey.

I am greatly indebted to the British military historian John Keegan for his masterpiece, The Second World War, and to Stanford professor David Kennedy for his monumental Pulitzer Prize winner, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 19291945. They were invaluable references.

Finally, when I was moved to write the original book, The Greatest Generation, it was a labor of love. I did not anticipate the changes it would bring to my own life. It has been, simply, the most fulfilling professional experience of my career and a deeply emotional personal experience. I feel privileged to have the opportunity to share these lives with you.

Part One

FROM THE DEPRESSION TO PEARL HARBOR

B ETWEEN 1929 AND the end of World War I in 1945, the world was in economic, political, military, and cultural turmoil on a scale unprecedented in recorded history. Earlier periods of great disruption brought on by the ambitions of the Roman empire or Genghis Khan, the bubonic plague in Europe or the changing of a dynasty in China, were largely regional events. But by the third decade of the twentieth century, air and sea transportation, communications technologythe telephone and radioand trade had made the world a much smaller place, where regional events had global ramifications. As the United States would learn in painful and costly fashion, the presence of two great oceans east and west did not insulate America from the ravages of economic chaos, the cruelty of nature, and the winds of far-off wars.

The American stock market collapse in 1929 was the beginning of a radical change of fortune for the United States, and it coincided with the rise of sinister political forces in the heart of Europe and in Asia. In Europe, Adolf Hitler was plotting to take over Germany with his National Socialist Party, the Nazis. In Asia, Japan was preparing to extend its political and military ambitions well beyond that tiny island nation.

To the average American, however, those distant developments were of little consequence when measured against the frightening state of the U.S. economy. The numbers were staggering. In three years stocks lost 80 percent of their value. The Ford Motor Company employed 128,000 workers in 1929; by 1931 that number had dropped to 37,000. American farmers who had sold a bushel of corn for 77 cents in 1929 were getting only 32 cents a bushel by 1932. By then the American economy was in a free fall. The sad effect was a plague of unemployment, bankruptcy, foreclosure, and broken dreams, from Wall Street to main street and beyond. Zelpha Simmons writes about the hardships her family faced during those years. As a young woman, Simmons held a full-time job as a bookkeeper, earning fifteen dollars a week. The only wage earner for a family of five, her family made it with a milk cow, garden and chickens and hard work.

Next page