General editors: Andrew S. Thompson and Alan Lester

Founding editor: John M. MacKenzie

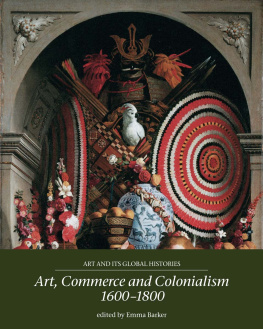

When the Studies in Imperialism series was founded by Professor John M. MacKenzie more than thirty years ago, emphasis was laid upon the conviction that imperialism as a cultural phenomenon had as significant an effect on the dominant as on the subordinate societies. With well over a hundred titles now published, this remains the prime concern of the series. Cross-disciplinary work has indeed appeared covering the full spectrum of cultural phenomena, as well as examining aspects of gender and sex, frontiers and law, science and the environment, language and literature, migration and patriotic societies, and much else. Moreover, the series has always wished to present comparative work on European and American imperialism, and particularly welcomes the submission of books in these areas. The fascination with imperialism, in all its aspects, shows no sign of abating, and this series will continue to lead the way in encouraging the widest possible range of studies in the field. Studies in Imperialism is fully organic in its development, always seeking to be at the cutting edge, responding to the latest interests of scholars and the needs of this ever-expanding area of scholarship.

Building the French empire, 16001800

SELECTED TITLES AVAILABLE IN THE SERIES

WRITING IMPERIAL HISTORIES

ed. Andrew S. Thompson

GENDERED TRANSACTIONS

Indrani Sen

EXHIBITING THE EMPIRE

ed. John McAleer and John M. MacKenzie

BANISHED POTENTATES

Robert Aldrich

MISTRESS OF EVERYTHING

ed. Sarah Carter and Maria Nugent

BRITAIN AND THE FORMATION OF THE GULF STATES

Shohei Sato

CULTURES OF DECOLONISATION

ed. Ruth Craggs and Claire Wintle

HONG KONG AND BRITISH CULTURE, 194597

Mark Hampton

Building the French empire, 16001800

Colonialism and material culture

Benjamin Steiner

MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS

Copyright Benjamin Steiner 2020

The right of Benjamin Steiner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS

ALTRINCHAM STREET, MANCHESTER M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN978 1 5261 4323 5hardback

First published 2020

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover image: Vintage World Map, 2015 Michal Bednarek, bednarek-art.com

Cover design: riverdesignbooks.com

Typeset

by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd

To Mi Anh

This book has been written far away from the places I have chosen to study from a perspective as a historian interested in the plurality and differences in the early modern world. Except for a journey to Martinique I undertook together with my wife in September 2017, I have not travelled to the places and regions of the former early modern French empire. I regret this very much, but I have soothed myself that this book could rather serve as an incentive to go to these places and explore them with the knowledge I gathered from the archival sources. From my experience in Martinique, however, I have learned that other things than written sources matter to historians, too. Besides the archeological evidence that I tried to collect from the respective literature one becomes aware of the materiality of the remains of the old building structures; at least I did when I visited the ruins of Chteau Dubuc on the Caravelle peninsula near the town of La Trinit on Martinique. I was also surprised to see how the places I knew from the sources were situated in relation to each other, how long one had to travel to reach them, and how the topographical situation really looked like. Today it is easy to drive around the magnificent landscape of this island. But it was different for the inhabitants of the seventeenth century to go from one place to the other, not to speak of the problems transport and logistics for the large building projects faced with the island's topography.

But I have not trained as an archaeologist or as an ethnographer who has the expertise to analyse and present the objects and locales in present times. I tried to get along with the written sources of the archives, dig through administrative correspondence, lists, and tables of building material and workers, the journals and memos of engineers, and tried to learn how a place like Martinique actually got included into the dominion of the French empire. What I discovered was that empire building has not been an achievement solely by European ingenuity, inventiveness, and audacity, but has relied on other non-European people, their actions and knowledge as well. I found this discovery important enough to describe it in detail and give it support with historical evidence. This objective, to show how a colonial empire was created by a diverse and plural group of people, remains the main purpose of my book. I hope the reader will excuse my lack of local knowledge of the present day and nonetheless gain insight from this book about this early period of colonialism.

As for myself, I have been inspired to continue my quest of learning more about the differences and entanglements in the early modern world, and will try to continue travelling to the places I described in this book: the settlements on the banks of the Senegal River, the cities of Puducherry (Pondichry) and Karikal in India, Atlantic Canada and its partly reconstructed town of Louisbourg, the Antillean islands of Guadeloupe and Saint-Kitts (Saint-Christophe), and the towns and cities of Haiti (formerly Saint-Domingue). Perhaps the readers of my book already have travelled to all of these places and know more about them than me. But I might give these readers more reason to see the interconnections and similiarties that bind these places to each other. This is a legacy of the early modern empire that was not held together by a dominant power in the metropolitan centre of France, but by the diverse community of people that inhabited these places before and after Europeans arrived at their shores and eventually left them again.

This book could not have been written without the generous support of the Max-Weber-Kolleg in Erfurt and the Kulturwissenschaftliche Kolleg in Konstanz over a period of three years. Both institutions provided me with not only the time and funding, but also the opportunity to discuss with colleagues the ideas and concept underlying this work. I received valuable advice, especially with regard to the question of the concept of empire, from scholars in a wide range of disciplines that congregate at these great centres of erudition. Hopefully, I have been able to translate their insights and guidance into a plausible narrative.

In particular, I would like to thank my colleagues from Erfurt, where I started working on this project. Martin Mulsow, Markus Vinzent, Jutta Vinzent, Riccarda Suitner, Susanne Rau, Knud Haakonssen, Jrg Rpke, and Martin Fuchs are some of the scholars that took great interest in my research. Their recommendations, comments, and critiques have helped to refine the argument and contributed to its clarity. I would like to express my special gratitude to Giovanni Tarantino, who encouraged me to think more about the connection between empire and emotion.