Copyright 2000 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Material London, ca. 1600 / edited by Lena Cowen Orlin.

p. cm.(New cultural studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8122-3540-1 (cloth : alk. paper).ISBN 0-8122-1721-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. London (England)History16th century. 2. London (England)history17th century. 3. Material cultureEnglandLondon. I. Title: Material London, ca. 1600. II. Orlin, Lena Cowen. III. Series.

DA680 .M38 2000 |

942.1055dc21 | 99-054378 |

Introduction

Lena Cowen Orlin

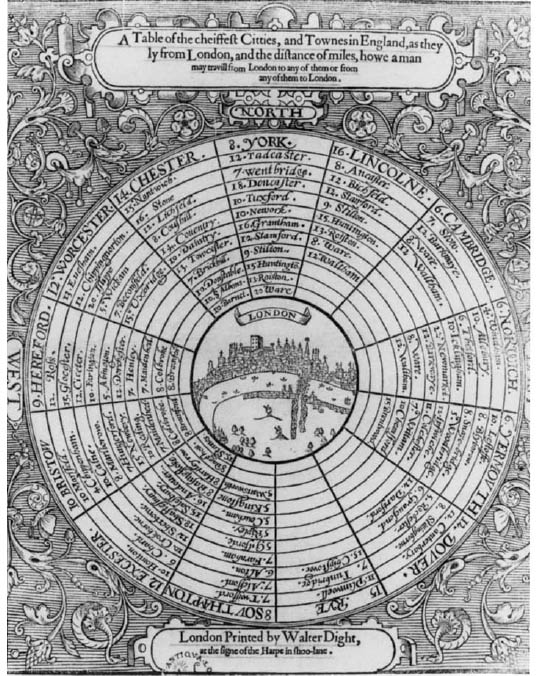

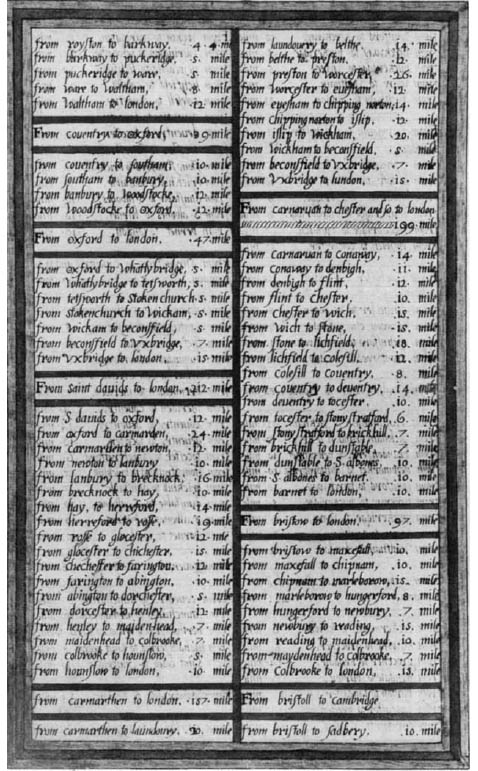

A Table of the cheiffest Citties, and Townes in England, a broadside printed about 1600, acknowledges that there were other urban centers in England besides Londonthirteen of them, including York, Lincoln, Norwich, and Bristol (fig. 1.1). The Table represents relatively few of these, however, and all are defined by their distance from the central cityscape, as they ly from London. The broadsides mileages are organized to allow for multiple manipulations of the data. Thus, because York is 8 miles from Tadcaster, which is 12 miles from Wentbridge, which is 7 miles from Doncaster, and so on, it can be concluded somewhat laboriously that York is 150 miles from London. It is also possible to calculate the distances from London to Doncaster (123 miles), from York to Wentbridge (20 miles), from Doncaster to Tadcaster (19 miles), and so on. But if this textual information must be puzzled out, the visual message of the broadside is clear at a glance: all English roads lead from London. Other towns and cities are laid out in concentric circles, as if on an imaginary astronomical chart, with London as the radiant sun for this crowded system of lesser planets and reduplicative asteroids.

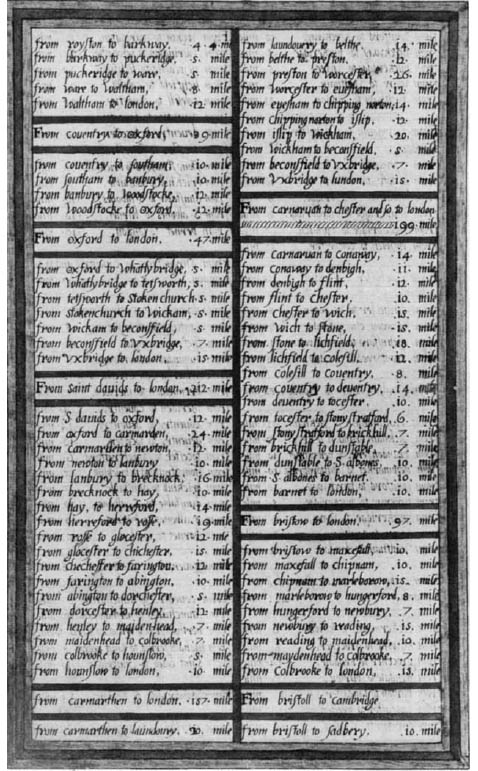

The mileages given in the Table are inaccurate by modern maps and measures, but they were evidently fairly standard for the time. In a great manuscript miscellany compiled a few years after the Table was printed, Thomas Trevelyon copied a chart for the geography of England, How a man may journey from any notable towne in England, to the Citie of London (fig. 1.2 shows one of five folio pages). The miscellany is a lavishly illustrated one, but in this case Trevelyon employed the textual format he seems to have preferred for such other densely informative charts as those on the age of the moon, aspects of planets, moveable feasts, and also, notably, A Table of the Rhombe and Distaunce, of some of the most famous Cities of the world, from the Honourable Citie of London (fig. 1.3). While How a man may journey repeats much of the information presented in the printed broadside, Trevelyon evidently consulted an independent source in incorporating more towns and more routes than the broadsides design allowed for. Despite the greater complexity of his data, Trevelyon also had a single organizing principle. In his chart, many journeys are punctuated with the catch phrase, and so to london, or, even more concisely, to london.

1.2 How a man may journey from any notable towne in England, to the Citie of London, from Thomas Trevelyons manuscript miscellany, Epitome of ancient and modern history (ca. 1606). Folger MS V.b. 232, fol. 35V.

Although the mileages in both the broadside and the miscellany can be calculated in both directions, in the former the emphasis is on travel from London, while in the latter the direction of default is the journey to London. The journey to is that with which history has traditionally been most preoccupied. The essential fuel for early modern Londons engines was the great number of people who migrated there from the hinterlands, seeking to improve their material conditions and swelling the capitals population. By 1600 London had overtaken all European centers except Naples and Paris demographically; by 1700 it would eclipse these two cities, as well, achieving parity with the great metropolis of Constantinople. In 1600, London was thus thoroughly established as the English national lodestone. All roads and many dreams led to London.

Thomas Platter wrote in 1599 that London is the capital of England and so superior to other English towns that London is not said to be in England, but rather England to be in London.

The authors in this volume represent most of the fields cited above. Their essays are grouped in five sections which point up themes that cut across these disciplines. The contributors to Part I wrestle most comprehensively and directly with the larger Meanings of Material London. Some consequences of Londons role as a trade center are explored in Part II, Consumer Culture: Domesticating Foreign Fashion. Part III, Subjects of the City, deals with social hierarchies and with the ways in which social change constituted particularly urban sensibilities and subjectivities around 1600. The concerns of Part IV are the citys Diversions and Display, its conspicuous consumptions, cosmopolitan tastes, and ready amusements. Part V, Building the City, describes structures built, rebuilt, and unbuilt in the great population boom of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.