Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2013 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

This book has been published with the assistance of The University of Texas at Austin.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hindman, Heather, author.

Mediating the global : expatrias forms and consequences in Kathmandu / Heather Hindman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-8651-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Foreign workers--Nepal--Kathmandu--Social life and customs. 2. Professional employees--Nepal--Kathmandu--Social life and customs. 3. International agencies--Officials and employees-Nepal--Kathmandu. 4. International business enterprises--Nepal--Kathmandu--Employees. 5. Labor and globalization--Nepal--Kathmandu. 6. Culture and globalization--Nepal--Kathmandu. I. Title.

HD8670.9.Z8K374 2013

331.6'2095496--dc23

2013025716

ISBN 978-0-8047-8855-7 (electronic)

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/14 Minion

Acknowledgments

THE DEBTS THAT ONE ACCRUES as part of the process of thinking about, researching and writing a book are diverse and innumerable. It was only midway into the process of this book that I began to understand its genesis in my grandparents expatriate experiences. Robert and Ethel Stewart lived in many locations, places I came to know through stories of life in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Japan, and later through trinkets and coins brought back from short trips to Asia, Africa, Europe and South America. While I long credited my grandfather for my wanderlust, I did not understand why I was drawn to understand Expatria until the project had already taken over my life.

This project and its intellectual merit, if there is any, developed from the rich intellectual communities I was embraced by, first at Reed College and later at the University of Chicago. The workshop culture at Chicago and the friends I developed out of it were the incubator, if not always a nurturing one, for this project. Colleagues in the workshops and coerced readers were invaluable in helping me to cohere the ideas that evolved into this book, including Anne Bartlett, Beth Buggenhagen, Kathleen Fernicola, Liz Garland, Sean Gilsdorf, R. Scott Hansen, Jenny Huberman, Matt Hull, Chris Nelson, Marina Peterson, Clare Sammells, Tara Schwegler, Amanda Seaman, Evalyn Tennant and Emily Vogt. I was also lucky to have a cohort of Nepal colleagues who were a source of comfort and challenge in two continents: Mary Cameron, Tatsuro Fujikura, Greg Grieve, Susan Hangen, Genevieve Lakier, Lauren Leve, Geeta Manandhar, Peter Moran, Katherine Rakin and Abe Zablocki. Jim Fisher, David Gellner, Mark Liechty and Kamala Visweswaran offered support in ways which will leave me always in debt. As a counterbalance for all the pain endured while in graduate school, the prodding of brilliant faculty is something I long to recapture, and I aspire to live up to my mentors, including Dipesh Chakrabarty, Barney Cohn, John Kelly, Rashid Khalidi, Saskia Sassen, David Scott and M. Rolph Trouillot.

Fieldwork incurs a special form of indebtedness, one that is more difficult to publically acknowledge. Workers at USAID and other aid organizations, members of the Rotary Club, various womens organizations and interest groups welcomed me and answered my questions with generosity and honesty. Many of those who were both friends and informants appear in pseudonym in this text. I hope David, John, Dianne and others will see this book as one that honors their lives and struggles. Research also brings financial debts, and I am grateful to the Social Science Research Council for funding much of the initial research of this project, and subsequently to the Committee on Southern Asian Studies at the University of Chicago and the Northeastern University Department of Sociology, as well as the South Asia Institute, the Mossiker Fund, the Co-op and the Vice President for Research at the University of Texas. Many valuable comments and ideas came from four anonymous reviewers and my supportive editors at Stanford, Michelle Lipinski and Stacy Wagner.

The institutions that have served as my home since Chicago have also provided important interlocutors, especially John Cort, Jill Gillespie, Chris Gilmartin, Whitney Kelting, Veve Lele, Sita Ranchod-Nilsson and Bahram Tavakolian. Andrea Hill and Leandra Smolin offered research assistance at key moments. At the University of Texas, the support of Kamran Ali, Craig Campbell, Kaushik Ghosh, Madeline Hsu, Sofian Merabet, Martha Selby, Snehal Shingavi, Nancy Stalker and Katie Stewart have been invaluable.

My mental health, such as it is, has been sustained in this process by Bob, Shirley and Jen Oppenheim, Lilith and Sally Hindman. If there are merits to this book, they are most likely due to the generosity of people I met in Nepal and Rob Oppenheim, whose partnership, challenge, support and love have made this adventure possible and at times even enjoyable. I cannot thank those who have supported me enough, while I accept that all shortcomings of this text undoubtedly trace back to the author.

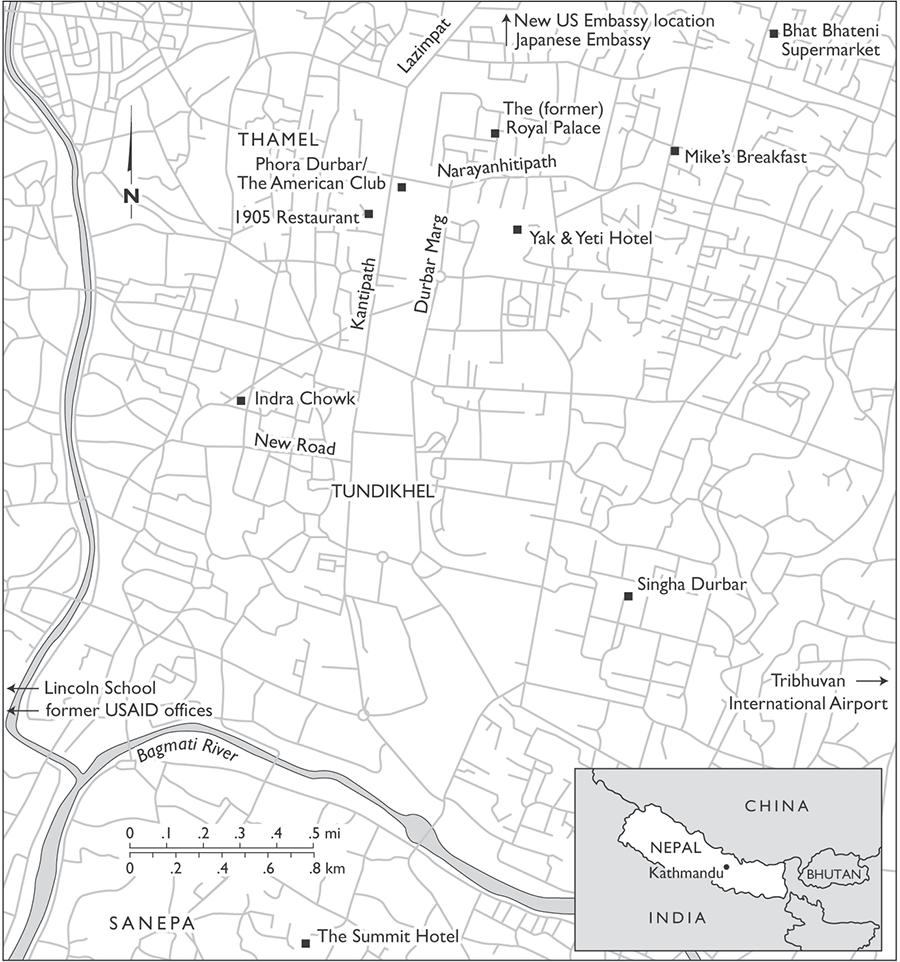

Map of Kathmandu

Introduction

Expatria in Nepal

SITTING AROUND THE HOTEL GARDEN, Iris and I were among the few remaining at the table by mid-afternoon from the group of expatriate women who met for lunch at least one Thursday a month. Much of the days conversation had centered on recent fluctuations in the value of the Nepali rupee against Western currencies and how this might affect the costs of goods and services. Concerns about this economic event had touched off a wider conversation about other financial worries shared by foreigners working abroad, including changes in home leave policies of employers and the distinct likelihood that several families soon to depart Kathmandu would not be replaced by new expatriate arrivals. After lunch, women began to drift away to run errands, pick up children or fill volunteer shifts until only the two of us remained. Iris had a rare free afternoon and seemed eager to talk about anything, from her daughters academic problems to her anxiety about her husbands contract not being renewed. After an hour of conversation, she worried that she was keeping me from important tasks, preventing me from doing my research. When I said that talking to people was a big part of what anthropologists did, she tried to clarify, asking why I was wasting time talking to her when there is so much culture all around us.

She gave herself little credit for a fascinating life. Iris had lived in nearly a dozen different countries. She had grown up betwixt and between, her German father having married an Irish woman, and the family shuttled between the two countries when she was a kid. She had married an Irish mechanic when she was young, just out of high school. Her life took an unexpected twist when he was offered a job in Indonesia for a substantial amount more than his starting salary, just a few years into the couples marriage. Although in her own words her life had been never dull, she could not see it being of interest to a scholar. During our conversation, she told stories of her familys adventures on three continents, but she would claim they were only the tales of a housewife and common to so many of the wives who had been at the lunch. Why would an anthropologist be interested in her, she wondered, when Nepal presented more culture of interest to anthropologists?