2015 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 c p 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Godreau, Isar (Isar P.)

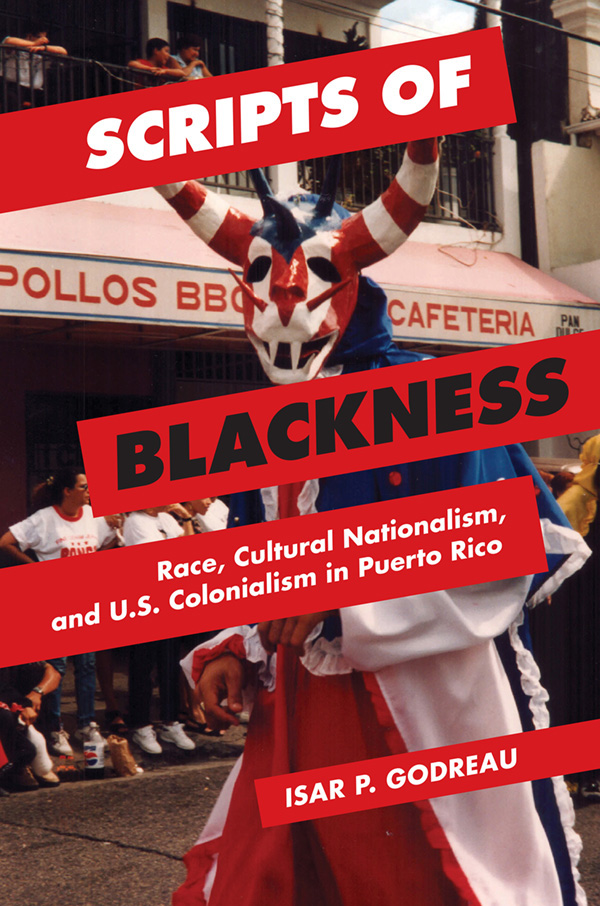

Scripts of blackness: race, cultural nationalism, and U.S. colonialism in Puerto Rico / Isar P. Godreau.

pages cm. (Global studies of the United States)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03890-7 (hardback : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-08045-6 (paper : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09686-0 (ebook)

1. Puerto RicoRace relations. 2. Puerto RicoColonial influence.

3. San Antn (Ponce, P.R.)Race relations. 4. Ponce (P.R.)Race relations. 5. RacePolitical aspectsPuerto Rico. 6. NationalismPuerto Rico. 7. United StatesRelationsPuerto Rico. 8. Puerto RicoRelationsUnited States. 9. GeopoliticsPuerto Rico. 10. GeopoliticsUnited States.

I. Title.

F1983.N4G63 2015

305.80097295dc23 2014019829

Acknowledgments

T his book came to completion thanks to the love and encouragement of my family, colleagues, and friends. Its publication, after more than eighteen years since fieldwork, is a testament of their long-standing enthusiasm. I am particularly grateful to Virginia Domnguez and Jane Desmond for rooting me on and providing such a supportive research environment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign through the International Forum for U.S. Studies (IFUSS) initiative. The opportunity to meet with other IFUSS scholars, present my work, use the wonderful library at UI, and have the great editorial assistance of Dr. Janet Keller contributed immensely to completing this work.

Over the years, the input of colleagues and friends such as Too Daz Royo, Juan Jos Baldrich, Jorge L. Giovannetti, Antonio Lauria, Jos (Pito) Rodrguez, Lena Sawyer, Patricia Landolt, Ivelisse Rivera Bonilla, Mareia Quintero, and Mariluz Franco helped me make sense of my fieldwork material. The support of Luis Santos while doing fieldwork and his ample knowledge of the islands geography made him an invaluable partner during the 1990s. Years later, keen commentaries offered by friends like Yarimar Bonilla, Hilda Llorns, Juan Giusti, Aaron Ramos, and especially my dear friend Errol Montes-Pizarro, who has lovingly served as my vctima inteligente for ten years, were crucial as I revised the text for publication. I am also thankful for the keen recommendations and enthusiastic response of the two anonymous reviewers, which tremendously improved this work.

Revisions for this book manuscript took place during my current tenure at the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey and had to be reconciled with institutional efforts to build and strengthen the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research there. I was lucky to have a supportive group of deans and co-workers like Vionex Marti, Yajaira Mercado, Neymar Ramos, Jannette Gavilln, Jessica Gaspar, Noel Caraballo, and many others who understood that I sometimes had to hide to write and never questioned the importance of that undertaking. The help of my diligent and sharp research assistant, Sherry Cuadrado, was also crucial for bringing this project to an end. She was my most constant interlocutor during the process of revising the manuscript for publication.

Institutional support for fieldwork also deserves recognition. The Wenner-Gren Foundation, the Research Institute for the Study of Man, the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, and the University of Puerto Rico (Presidential Scholarship Program) supported different stages of my fieldwork from 1993 to 2001. I am especially grateful and indebted to the Ford Foundation and the fellows who supported my academic development at different stages of this journey. Thanks to that support, I was able to meet and work with colleagues and anthropologists from many different institutions: the University of California at Santa Cruz, Johns Hopkins University, the University of South Florida, and the University of Texas at Austin. I had the benefit of meeting wonderful professors and senior mentors such as my advisor Lisa Rofel and professors Ana Tsing, Virginia Domnguez, Olga Njera Ramirez, Ann Kingsolver, Carolyn Martin Shaw, Franklin Knight, Sidney Mintz, Rolph Trouillot, Kelvin Yelvington, and Charles Hale. Sid Mintz, in particular, encouraged me to pay attention to the history of Puerto Rico and of the Caribbean. The historical and political-economy-informed vision that he and scholars like Rolph Trouillot, Sara Berry, and fellow graduate students brought to the graduate program of anthropology at Hopkins had a crucial impact on my approach to questions of race, racism, and national identity in Puerto Rico. Back then, I felt like this framework was at odds with the postmodern and discursive orientation that my base institution (UC Santa Cruz) took to these questions. But I now realize I was quite fortunate to have been exposed to both. I hope the book shows this.

During my fieldwork in Ponce, local government agencies such as the Oficina de Desarrollo Comunal y Eonmico and the Oficina de Ordenamiento Territorial provided crucial information. I am also grateful to Humberto Figueroa, Carmen Rivera, Gary Gutirrez, and the late Rign Dapena for sharing their knowledge of Ponce with me, and to Gladys Tormes, who was an invaluable resource at Ponces Historical Archives. Thanks also to Yarimar Bonilla, Keith B., Lucio Oliveira, David Gasser, and Jos Caldern for their help with photos and images.

Of course, none of this support would have yielded a book had it not been for the people of San Antn. My greatest debts are to the families and community leaders who took me in to their homes and let me participate in their community activities, answering my questions and accepting my intrusions with hospitality and patience. Most of their names appear as pseudonyms in the book, but I want to give credit for their assistance and thank them individually here. Most of all, I am indebted to the late Doa Judith Cabrera and her daughter Mara Judith Banchs Cabrera, who first introduced me to the community and who allowed me to spend many afternoons in their yard. It was through the wise eyes of Doa Judith and the committed disposition of her daughter Mara Judith that I first came to know the barrio. Their trust made it possible for me to do fieldwork in the community, and for that I will always be grateful. I also thank Felcita Tricoche Santiago, her daughters Rosa and Nilda, and her granddaughter Mara for letting me into their homes and for sharing their life histories. Luisa Franceschi, Carlos (Cao) Vlez Franceschi, and their family also shared invaluable information. In addition I thank Paula and her daughter Jeamaly Rivera, who offered invaluable assistance with my archival research in Ponce. I am especially grateful to the

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.