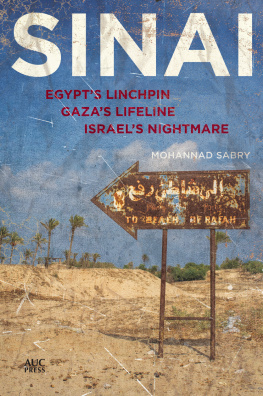

This electronic edition published in 2015 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2015 by Mohannad Sabry

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 728 7

eISBN 9781 61797 695 7

Version 1

M any of the military officers, Bedouin figures, and politicians who I met and interviewed while researching this book, were convinced that the cultural, social, economic, and political isolation of the Sinai Peninsula was a natural outcome of it being a military zonehighlighted by extreme measures such as requiring a military permit to travel in or out of the peninsula between the nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, which sparked Egypts war with Israel, Britain and France, and the full Israeli withdrawal of 1982. It was viewed by most as a rugged battlefield, and treated by consecutive Egyptian rulers as simply a route through which mobilizing armies could pass and the stage of wars with Israel, since its founding in 1948. But after the signing of the Camp David Peace Accords between Egypt and Israel in 1978, and following the full Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in 1982, Sinai remained isolated, its Bedouin population marginalized and its development and economy excluded from the rest of the country.

The military permits of the pre-Camp David era are no longer required, but have been replaced by dozens of security checkpoints that stifle the movement of people more than the difficulty of acquiring permits. The war with Israel came to an end, but throughout the thirty years of Hosni Mubaraks rule over Egypt (from 1981 to 2011), not a single university campus was opened in Sinai (with the exception of a private university owned by a business tycoon with close ties to the military). As for development and investment, aside from beachside hotels and resorts, where Bedouin are mostly not allowed to work, the overwhelming majority of the peninsulas 61,000 square kilometers has remained as lifeless and barren as ever.

To further secure the continuation of its utterly failed policies in Sinai, Mubaraks regime imposed a complete media and information blackout on everything related to the eastern province. For the first twenty years of Mubaraks rule, reporting in Sinai, publishing about its grievances, or even applauding the repeatedly promised (but never executed) development plans, either in state-owned or independent media outlets, had to go through the filters of state security or await a permit from the Ministry of Defense. In the last decade, between 2000 and Mubaraks downfall in 2011, restrictions on the media in Sinai were theoretically lifted within a broader nationwide plan to project an image of democracy. Reporters were allowed to travel freely to al-Arish, Sheikh Zuwayyed, and Rafah, whereas before they had only been permitted access to the southern beaches to cover Mubarak receiving world leaders at the lavish mansions and resorts of Sharm al-Sheikh. However, even after media restrictions were supposedly eased, the consequences of publishing an article deemed annoying to the regime remained: criminal, state security, or military trial accompanied by workplace intimidation and the possibility of losing ones job from a given media institution. Moreover, as I have personally witnessed a number of times at security offices in Sinai, reports were regularly written by security officers and sent directly to newspapers to be published under the names of specific journalists. Not so surprisingly, during the last decade of this Mubarak-style freedom, the most memorable writings about Sinai were those about the Taba, Sharm al-Sheikh, and Dahab bombings in 2004, 2005, and 2006mainly because of the large number of foreign nationals who fell victim to the terrorist attacks there, and their close proximity to Mubaraks residence in his last ten years in power.

Over his thirty years in power, Mubarak succeeded in equating the Sinai Peninsula, in the minds of Egyptians and the majority of the world for that matter, to the southern beach resorts reserved mainly for foreign tourists; the clich of the 1973 victory against Israel; and a lifeless desert inhabited by Bedouin outlaws and traffickers.

On January 25, 2011, when Egyptian protesters marched through the streets of the capital Cairo and held sit-ins across the country, including around Sinais security compounds and government offices, the relentless reporters and activists of the peninsula were finally liberated. They broke the barriers of fear, stood in the face of a murderous police apparatus and for the first time, possibly in their lives, documented what happened in Sinai, for the world to watch, even if this was largely ignored as media organizations remained focused on the capital Cairo and Tahrir Square. Mubaraks blackout, financed by billions of dollars allocated to the construction of prisons and torture chambers run by State Security, rather than schools and hospitals, was finally brought down, along with the men who supervised it.

Despite the unprecedented freedoms gained in the aftermath of the uprising, everyone seemed to believe that it was temporary. When discussing this book with trusted contacts in Sinai in the years following the revolution, I encountered genuine encouragement, but also serious warnings. One prominent Sinai activist advised me that there will be an inevitable price that you will pay for taking such a step. When considering who the book would anger, I was told that it would be easier to look for those who the book would not infuriate.

I decided to pursue the book project; Mubaraks downfall had empowered activists and community figures and led to a precious flow of information. Many would still only talk on condition of anonymity, but were discussing subjects they had never dreamed of whispering even to their closest acquaintances under the oppression of Mubaraks regimetestimonies of torture and police brutality surfaced after years of silence induced by fear. But within the atmosphere of greater freedom, which prevailed until 2013, some of the peninsulas most sensitive subjects remained a taboo. Arms trafficking, which mainly supplied the Muslim Brotherhoods offshoot Hamas in Gaza, was one of the most difficult subjects to discuss or report on, followed by the Brotherhoods murky influence in Sinai and the rise of Islamist militants, whose attacks had started even before Mubaraks downfall.

My investigative reporting in Sinai earned me my first threat in late 2012, around my work on armed Islamists. The atmosphere was severely polarized, and several Bedouin leaders had been assassinated for their public condemnation of the militant groups and their opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood regime. In January 2013, North Sinai-based reporter Muhamed Sabry (despite his name, not a relative of mine) was detained by the military for filming in Rafah; he was put before a military tribunal, sentenced to a suspended jail term, and then released. After the incident, I began learning of threats sent to colleagues one after the other because of their determined reporting across the peninsula.

Right after Morsis ouster on July 3, 2013, and in the context of the avalanche of terrorist attacks across the peninsula and mainland Egypt that followed, the crackdown on journalists operating in Sinai increased significantly, reaching a peak with the arrest of my colleague Ahmed Abu Draa. Detained on September 5 in al-Arish, a few hours after I left him to travel to South Sinai, he was imprisoned in Ismailiyas notorious al-Azouli military prison for one month before standing before a military trial that sentenced him to a suspended jail term.