Queena N. Lee-Chua - Lifeline

Here you can read online Queena N. Lee-Chua - Lifeline full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lifeline

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lifeline: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lifeline" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lifeline — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lifeline" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

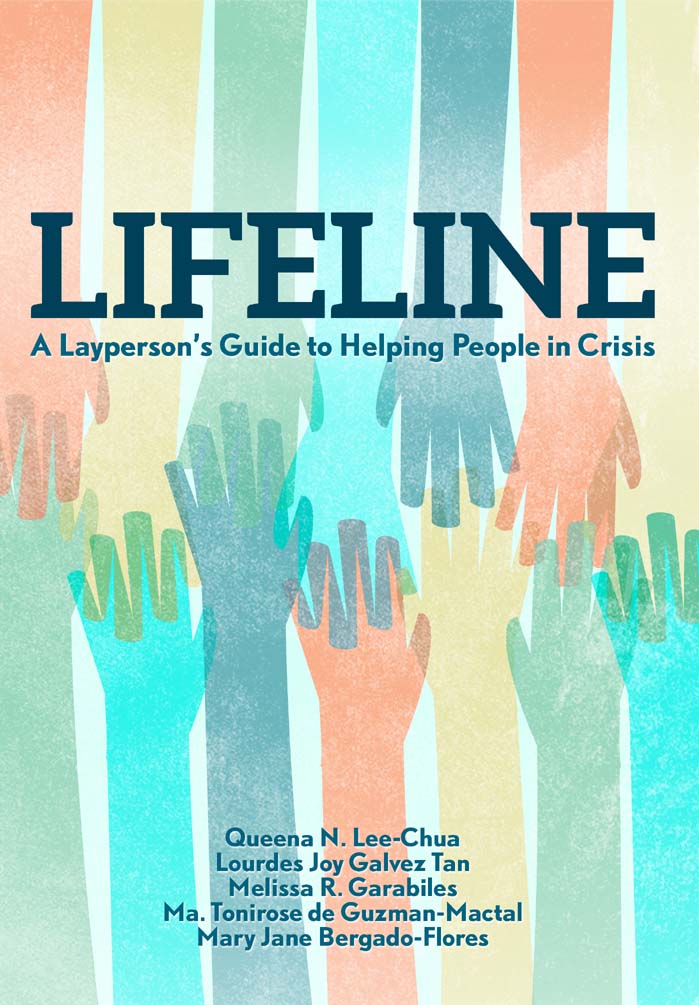

Lifeline

A Laypersons Guide

to Helping People

in Crisis

Queena N. Lee-Chua

Lourdes Joy Galvez Tan

Melissa R. Garabiles

Ma. Tonirose de Guzman-Mactal

Mary Jane Bergado-Flores

Lifeline: A Laypersons Guide to Helping People in Crisis

by Queena N. Lee-Chua, Lourdes Joy Galvez Tan, Melissa R. Garabiles, Ma. Tonirose de

Guzman-Mactal, Mary Jane Bergado-Flores

Copyright to this digital edition 2016 by Queena N. Lee-Chua, Lourdes Joy Galvez Tan, Melissa R. Garabiles, Ma.

Tonirose de Guzman-Mactal, Mary Jane Bergado-Flores, and Anvil Publishing Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any

means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission except in the

case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published and exclusively distributed by

ANVIL PUBLISHING, INC.

7th Floor Quad Alpha Centrum

125 Pioneer Street, Mandaluyong City

1550 Philippines

Trunk Lines: (+632) 477-4752, 477-4755 to 57

Sales & Marketing:

Fax: (+632) 747-1622

www.anvilpublishing.com

Book design by Clarissa Ines (cover) and Ani V. Hablan (interior)

ISBN 9789712733598 (e-book)

Version 1.0.1

A Student Talks to an Acquaintance

Involved in Extreme Self-Injury

A Teenager Talks to a Classmate

Displaying Signs of Self-Injury

A Teenager Talks to a Friend

Whose Sibling Died in an Accident

A Volunteer Talks to a Family

About Evacuation Before an Emergency

A Teacher Talks to a Student

Whose Home Was Flooded

A Teacher Talks to a Grieving Student

Whose Mother Died in a Disaster

CRISES AND TRAUMA take on many guises, but the results are eerily similar: inability to cope, overwhelming stress, mental confusion, emotional disturbances, the desire to end the pain at any cost.

While problems beset all of us, in the past decades, research in the US and statistics in the Philippines reveal that young people today (roughly speaking, those born after the mid-1990s) appear to be particularly at risk for severe mental, emotional, and social problems. Causes have been posited: lack of loving and stable families; helicopter parents who refuse to let children suffer any discomfort; unrealistically high and stringent parental or personal expectations conditioned on perfection; violent deaths or suicides glamorized in media; addiction to a virtual world more seductive than the real one; social isolation due to fragmented families, gadgets tailored to individual tastes, and gated subdivisions; and relentless competition that starts from preschool and never ends; among others.

In April 2013, Queena taught a graduate class on Trauma and Recovery, where various problems were discussed, together with techniques to help troubled people deal with them. Since the students were mainly training to be counselors, each of them was required to role-play counseling sessions in front of the class, to be critiqued by everyone. What would you say to a student who wants to jump off a building? To a mother grieving over the death of her child? To a boy who lost his home in a flood? To a teen who cuts herself because she feels hopeless?

These sessions were the highlight of the course. After all, what is the use of theory if it cannot be put into practice? Some graduate students were able to counsel with equanimity, while others fumbled for the right words to say. Many confessed that they became fearful when faced with someone in pain, because what if what they said or did made matters worse?

Nevertheless, the class responded, and everyone had his or her chance to try to help a troubled individual. Afterwards, many in the class asked for sample scripts, which they asserted would be helpful for teachers, students, parents, and even trained professionals.

From June to October 2013, some clinical psychology doctoral candidates took a second, more advanced, course, and the goal was clear: do extensive research on a specific problem, gather Philippine data if available, and most importantly, create sample scripts to help not just counseling professionals but also teachers, students, parents, friends, priests and nuns; in short, those who want to help but do not know how.

Various drafts were made, revisions done, scripts reworked. Eventually, scripts were uploaded online for both trauma classes and made available for free, as long as they were used for educational, counseling, or therapeutic purposes. Several people began using the scripts in their schools, classes, and families, and they attested to their usefulness.

In the meantime, the numbers of people at risk continued to grow. As of late 2015, we have been handling too many cases of vulnerable young people (and adults). Faculty and student facilitators request for guidance, and so do parents and guardians. We also work with the school administrators to streamline protocol.

The cases were myriad: suicidal ideation and intent, self-harm (cutting, pulling out hair, banging the head), eating disorders (binging and purging, anorexia), anxiety disorders (panic attacks, generalized anxiety), depression (dysthymia, cyclothymia, major depression), autism (Aspergers, moderate autism), attention disorders (with or without hyperactivity), addiction (alcohol, gaming, gambling, nicotine, drugs, eating), natural disaster trauma (from floods, earthquakes, typhoons), grief (death of parents, death of siblings, death of children, death of friends), and so on. The list seemed endless.

While each problem is significant, in this book, we have decided to focus on what we feel to be the most urgent or the most universal: How do we help young people at risk of self-harm or suicide? How do we help survivors of natural disasters? How do we help anyone who is grieving over the death of a loved one?

Note: This book is NOT a therapy manual. It should NOT be used as a substitute for professional help. Think of the guidelines contained therein as psychological first-aid, to be applied in urgent and immediate cases (for instance, a child bids you goodbye because he has decided to end it all), or to prevent more serious problems (for example, a student fails a test and confides that she is feeling depressed).

For serious cases, first aid is not enoughvulnerable individuals SHOULD BE REFERRED to trained professionals, and this book gives you ways to do so.

WHILE THIS BOOK is a group effort (from the combined experiences of the professor and more than a dozen graduate students in basic and advanced Trauma and Recovery classes), we would like to acknowledge the principal authors of the specific topics. Queena provided the overview of the various crises and edited the various chapters; Joy wrote on suicide, Mel on self-harm, Toni on grief, and Jane on natural disasters.

Queena says: I would like to thank Lota Teh, former Psychology Department chair who encouraged the work of both trauma classes; Honey Carandang, Outstanding Social Psychologist, whose trauma class I took two decades ago; and Fr. Ben Nebres, National Scientist and former Ateneo president, whose wisdom on fragile students crystallized our experiences. My thanks go also to Teya Paulino, Joy Salita, Bobby Guevarra, Rene San Andres, Ediboy Calasanz, Jojo Hofilea, Flor Francisco, Banjo Bautista, Noel Cabral, Cholo Mallillin, John Paul Vergara, Jo-Ed Tirol, Chris Peabody, Eurlyne Domingo, Henri dela Cruz, past and present Ateneo faculty and administrators, and countless undergraduate and graduate students (you know who you are!) who in one way or another have helpedand continue to helptroubled young people. Thank you to Xandra Ramos of National Bookstore, Karina Bolasco, Gwenn Galvez and Ani Hablan of Anvil Publishing, for your constant support of books that matter. Eternal love and gratitude to my husband Smith, our son Scott, and our dog Hershie, for your understanding, patience, comfort and unconditional love.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lifeline»

Look at similar books to Lifeline. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lifeline and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.