Copyright 2016

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

www.brookings.edu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Kettl, Donald F., author.

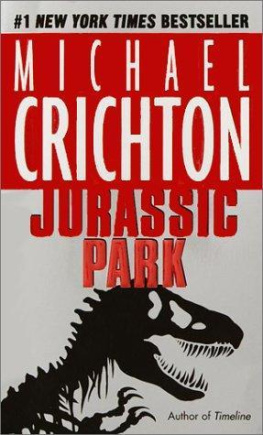

Title: Escaping jurassic government : how to recover Americas lost commitment to competence / Donald F. Kettl.

Description: Washington, D.C. : Brookings Institution Press, 2016.|Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015051473 (print)|LCCN 2015040127 (ebook)|ISBN 9780815728023 (epub)|ISBN 9780815728115 (pdf)|ISBN 9780815728016 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Public administrationUnited States.|Administrative AgenciesUnited StatesManagement.|Government accountabilityUnited States.|Transparency in governmentUnited States.|Government ProductivityUnited States.|Organizational effectivenessUnited States.|BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / Government / National.|POLITICAL SCIENCE / Government / Legislative Branch.|POLITICAL SCIENCE / Public Policy / Social Policy.

Classification: LCC JK421 (print)|LCC JK421 .K478 2016 (ebook)|DDC 351.73dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015051473

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Janson Text LT Std Roman

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

Preface

T HERE IS A LARGE AND growing gap in American government, between what people expect government to do and what government can actually accomplish. Citizens look at what the private sector does, from overnight delivery of products purchased with a single click to one-stop online access to their finances, and they wonder why government cannot do as well. For the public sector, theres the endless parade of media tales about government failures. Inside Internet echo chambers, social media reinforces a cynical and sometimes even nasty view of government. Candidates for office have not only discovered they can make hay out of attacking Washington, but they have increasingly suggested that the policy game has been captured by a professional political class, which has rigged the system to benefit insiders while freezing out ordinary citizens.

Its not just cynics, reporters, and social media ideologues who wonder about government failures. In a sweeping critique of American government, Francis Fukuyama has argued that the rising power The gap has widened between citizens expectations and governments performance. Theres also an underlying sense that citizens have become walled off from the government theyre taxed to provide.

Some of this, of course, is the product of citizens risingand sometimes impossibleexpectations about what government ought to do for them. No matter the issue, the first instinct when problems arise, even among the biggest advocates of the smallest government, is to see government as the cavalry and wonder why it doesnt arrive faster to help save the day. Theres virtually no problem that citizens dont call on government to solve, from flooded basements and giant sinkholes to help after epic natural disasters and protection from lone-wolf terrorists. Almost no one likes big government, but no one expects to have to cope with problems alone.

And thats laid the foundation for the biggest challenge for American government in the 21st century. As 18th-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau contended, government is based on a social contract with its citizens. The combination of the rising expectations about what government should do and the manifest challenges in meeting those expectations has frayed, perhaps even fractured, that contract. So, too, has the growing sense that government is in business to help those hard-wired into its operations, at the expense of citizens locked outside. When it comes to government, especially at the federal level, there are growing worries about what is possible but no lack of challenges to attack.

Figuring out how we got to this place is the goal of this book. It begins with a simple premise. Modern American government grew from a core belief, supported by both Republicans and Democrats, that emerged with the Progressives in the late 19th century: whatever government chose to do, it had a responsibility to do it well. In the last decades of the 20th century, however, conflict over governments mission increasedand the shared commitment to competence eroded. We continued to ask more of government, from ending poverty and eliminating pollution to defending the homeland and protecting the financial system. We became increasingly enraptured by the notion that the private sector could do anything we wanted to do better than government could do it. We lost trust in government and its ability to perform. So, to work through these dilemmas, we relied ever more on strategies that have interwoven governments role into the private and nonprofit sectors. Government increasingly is everywhere, because we want it to do more. But weve worked hard to undermine its capacity and to wipe away its fingerprints, because we dont trust government to do it.

As I explain in the book, these trends have, in many cases, eliminated the line of sight between citizens and what their government does for them. In turn, this has unraveled the social contract, because the parties have increasingly lost the connection with each other. Moreover, as government has invented new tools to meet citizens impossible expectation of more help without more government, it has not invented the skills needed to use these tools well. That has eroded trust in governments ability to perform.

Half of the book focuses on explaining how we got here; the other half lays out a hopeful theory about how we can crack this nut. It arrays four scenarios through which government can evolve in the coming decades. One seems both most likely and most positive: a government that develops new skills, through powerful new data tools and better managers to use them, to leverage the partners on which it relies to serve the public. We have proven we can make this model work, but the consequences if we do not are dire. The dinosaurs went extinct because they failed to adapt, and the same could happen to American government. But, like Ebenezer Scrooges vision of the ghost of Christmas yet to come, this represents a future that may occurbut which need not occur, if we have our civic wits about us. We have it in our power to write a fresh draft of the social contract for the 21st century, if we put our minds to recovering the nations lost commitment to competence. That, I conclude, is the key to escaping the Jurassic government that plagues us, a government that has increasingly fallen out of sync with its environment.