Copyright page

Copyright Donald F. Kettl 2017

The right of Donald F. Kettl to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2017 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2245-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2246-0 (paperback)

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11 on 15 pt Sabon

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon.

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Figures and Table

Figures

Trust in institutions

Public trust in government

Confidence in national government

Confidence in national government: change from 2007 to 2014

Confidence in national parliaments (2015)

Confidence in national parliaments: percentage change, 20042015

Confidence in American institutions

Social trust and income inequality

Trust in others by gender, age, education, and income

US: weekly earnings of full-time workers aged 16 and older, by percentile

Income inequality: before and after taxes and transfers

Effect of age on support for Brexit/Leave and for Trump

Table

Confidence in American national institutions

Acknowledgments

An author wrestling with a puzzle as complex and long-lasting as trust in government requires a great deal of help. The basic issues go back a very long way; newer problems spill out daily. Pulling them all together into a single, short book is a daunting task. I want to thank Polity's editor, Louise Knight, who first inspired me to tackle this topic. Her insights into the things most worth doing were truly invaluable, and her enthusiastic support along the way has been inspiring. Nekane Tanaka Galdos, assistant editor at Polity, provided wonderful support at every step on the way. I'm also deeply appreciative of Leigh Mueller, whose keen skill as a copy-editor unquestionably made the book sharper and clearer.

In refining the book's arguments, I'm indebted to the reviewers for Polity, who were especially careful in their reading and particularly helpful in their recommendations. Let me give my special thanks to Matthew Wright of American University and Jack Citrin at the University of California, Berkeley.

In addition, a greatly valued colleague, John DiIulio of the University of Pennsylvania, provided invaluable suggestions for improving the manuscript.

Finally, I want to thank my wife, Sue, whose own insights into the values that last have been an inspiration to me for the many years I've been lucky enough to have her as my spouse.

The Puzzle of Trust

The rising tide of distrust in government is surely one of the biggest challenges facing the world's democracies in the twenty-first century. The center of the problem is the United States, where trust in public institutions has dropped precipitously since the 1960s. In fact, according to public opinion surveys, Congress is less popular than head lice, cockroaches, traffic jams, and colonoscopies. But the problem is not just an American one. Edelman, a major global research firm, has surveyed 28 countries and found that more than half of the public in more than half of the countries distrust their governments. The US, in fact, is about in the middle. Major democracies like Germany, Britain, Sweden, and Japan rank even lower.

Distrust in government often seems a largely US-centered problem, but its reach stretches much farther. Moreover, although distrust in government often seems a relatively recent problem, we will see in this book that it is an eternal, universal, and inescapable problem, not bound by time or place. At the same time, however, distrust is bad and getting worse. It is spreading, fueled by shock waves of populism. And it poses large, important challenges to the world's major democracies that demand attention.

That, in turn, frames the basic puzzle for this book. If distrust is inevitable but getting worse, if it has deep roots in the US but is spilling into other countries as well, is there anything that we especially the officials we elect to lead us can do about it? Can they earn our trust?

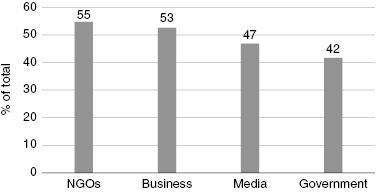

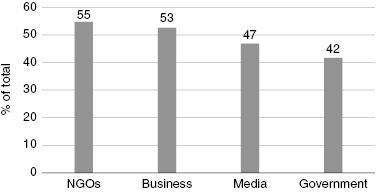

The basic patterns are clear. In the 28 nations that Edelman surveys, citizens trust nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) more than businesses, businesses more than the media, and the media more than government (see figure ). Since government is the one institution whose leaders we collectively choose, and the one institution we count on to work on behalf of all of us, the rising tide of distrust is especially worrisome. Can we take action, by all of us for all of us? If distrust splinters our capacity to work together, the prospects for the survival of democracy are bleak.

Trust in institutions

Source: 2016 Edelman Trust Barometer, Executive Summary (2016), www.edelman.com/insights/intellectual-property/2016-edelman-trust-barometer/executive-summary.

But this book does not have a gloomy conclusion. The prospects for earning trust are, in fact, quite good if we have the wits to discover and use the strategies that will help us to do so. After exploring how we got into this fix, we will examine how democratic government can in fact earn trust and, in the process, at least modestly help to restore our confidence in its ability to govern us.

Trends in trust

Trust is a deceptively complex phenomenon, so definitions are important. In the political setting, trust occurs when citizens look at how their governments operate and conclude that their political leaders will keep their promises in a just, honest, and efficient way.

But trust operates in two dimensions. Social trust describes the relationships among individuals, leading them to have confidence in their interactions with each other and, therefore, to cooperate in seeking common ground. Social trust thus supports governmental institutions, because individuals who trust each other are more likely to trust the decisions their governments make on their behalf. Political trust reflects the direct relationship between citizens and their governments. Trust in political institutions is a reflection of the confidence that individuals have that government does what they want and expect. The two dimensions of trust, of course, are closely related. But it is the erosion of political trust that is most worrisome for democratic institutions. Social trust captures the complicated relationships between individuals and how these interconnections spill over into institutions. Political trust captures the struggles in the basic democratic relationship, between voters and governing institutions. Problems in political trust create much more direct worries about democracy's ability to govern. In this book, I will focus most on political trust, as we seek to understand the answers to important puzzles. What are the trends in political trust? Does it matter? And what can we do about it?

Next page

Trust in institutions

Trust in institutions