Copyright 2017 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ervin, Keona K., author.

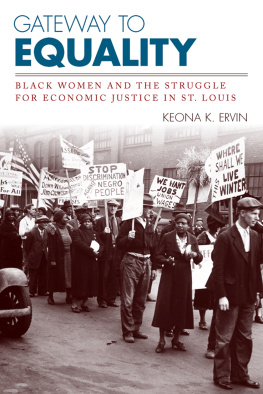

Title: Gateway to equality : Black women and the struggle for economic

justice in St. Louis / Keona K. Ervin.

Description: Lexington, Kentucky : University Press of Kentucky, 2017. | Series: Civil rights and the struggle for Black equality in the twentieth century | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019635| ISBN 9780813168838 (hardcover : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780813169873 (PDF) | ISBN 9780813169866 (ePub)

Subjects: LCSH: African American womenMissouriSaint LouisSocial conditions20th century. | African American womenMissouriSaint LouisEconomic conditions20th century. | Working class womenMissouriSaint LouisHistory20th century. | EqualityMissouriSaint LouisHistory20th century. | Social justiceMissouriSaint LouisHistory20th century. | Saint Louis (Mo.)Social conditions20th century. | Saint Louis (Mo.)Race relations20th century. | Saint Louis (Mo.)Economic conditions20th century.

Classification: LCC F474.S29 N4334 2017 | DDC 305.48/896073077866dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019635

A portion of this work was originally published in slightly different form in International Labor and Working-Class History, Journal of Civil and Human Rights, and Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture and Society.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the association of

American University Presses |

Abbreviations

ACTION | Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes |

AFL | American Federation of Labor |

CCC | Colored Clerks Circle |

CCRC | Citizens Civil Rights Committee |

CIO | Congress of Industrial Organizations |

CORE | Committee (Congress) of Racial Equality |

CPUSA | Communist Party USA |

FEPC | Fair Employment Practices Committee |

HDC | Human Development Corporation |

HL | St. Louis Housewives League |

ILGWU | International Ladies Garment Workers Union |

MOWM | March on Washington Movement |

NAACP | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People |

NIRA | National Industrial Recovery Act |

SLHA | St. Louis Housing Authority |

TUUL | Trade Union Unity League |

UC | Unemployed Council |

UCAPAWA | United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America Union |

UL | Urban League |

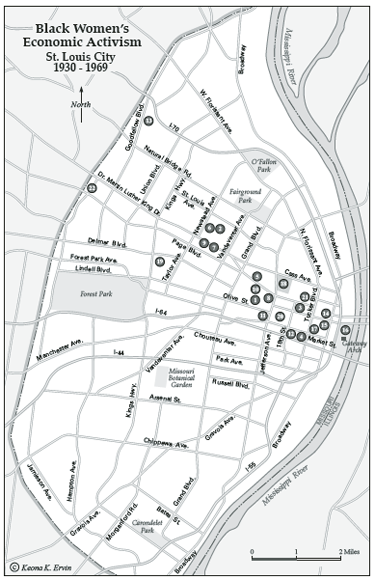

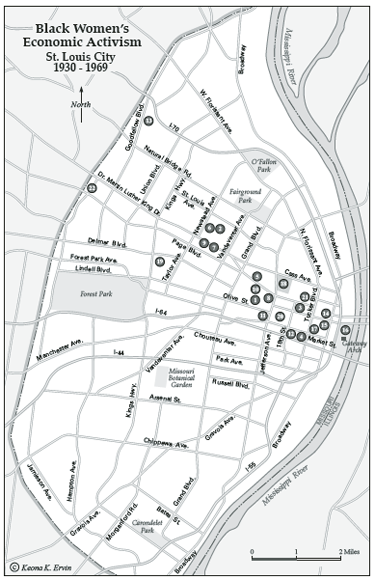

(1) Phillis Wheatley YWCA, (2) Poro Building, (3) Funsten Nut Company, (4) City Hall, (5) Labor Lyceum, (6) Colored Clerks Circle Headquarters, (7) Woolworth Store, (8) Woolworth Store, (9) Gerkens Hat Shop, (10) St. Louis Urban League Headquarters, (11) March on Washington Movement Headquarters, (12) Municipal Auditorium, (13) U.S. Cartridge Small Arms Plant, (14) Stix, Baer and Fuller, (15) Famous-Barr Company, (16) Mississippi Revels Revue, (17) ILGWU Labor Stage, (18) Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project, (19) St. Louis City Welfare Office, (20) St. Louis Housing Authority, (21) Plymouth House, (22) California Manufacturing Company.

Introduction

The Labor of Dignity

Black Working-Class Womens Organizing in the Gateway City

Not long after St. Louisans entered into the new year of 1969, the final year of a decade of significant social upheaval at the local and national level, thousands of public-housing tenants struck against the St. Louis Housing Authority (SLHA). Together, the black working-class women whose lives were at the center of the debate over the future of the city staged one of the largest and earliest demonstrations of its kind. National news outlets provided coverage, politicians at the local, state, and national level weighed in and amended or adopted policies as a result, and several strike leaders emerged as national figures. While they issued numerous demands to city officials, above all, dissidents called for dignity and control. Drawing upon support from key leaders, public sympathy, and the sustainable political communities that they had built over time, strikers demanded the redistribution of power and a greater allocation of resources to manage their own affairs and become key brokers in decision-making processes. Their hard-hitting politics and critical views about municipal authority and governance were deeply rooted in their insistence on making black working-class womens survival a matter of public concern.

Winning their demands after months of mobilization, the strikers put St. Louis on the proverbial map as a site of transformative black working-class struggle, and they also made it possible for the St. Louis public-housing system to emerge as a national exemplar of the tenant management model. Most importantly, however, by engaging in collective action that exposed the connections between housing, employment, and working-class residency in a declining, deindustrializing American city, the tenants who refused to pay rent cemented black womens status as influential members of the citys working class. Women selected the strike method as their political weapon of choice, they established close ties with unions to advance their cause, and they articulated their battle over housing as a problem of a lack of access to jobs and economic dignity. These elements not only reflected their political sophistication; they also pointed to black working-class womens political legacies in the Gateway City. While contemporaries tended to hold the view that the rent strike was at best a spontaneous and disorganized eruption of working-class disaffection with those in power, an accurate examination reveals that what transpired did not emerge in a vacuum. Instead, the strike was the culmination of three decades of black working-class womens economic activism and labor organizing. The organizing tradition that black working-class women in St. Louis inspired and led set the stage for and accentuated the conceptualization of the rent strike as a struggle waged by black working-class women for economic dignity.