Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

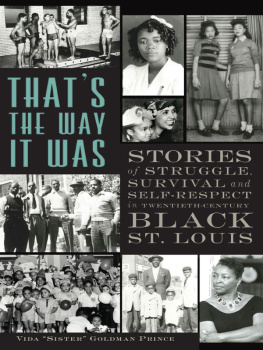

Copyright 2013 by Vida Goldman Prince

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.038.7

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.970.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

In memory of my parents and son

Vida Tucker Goldman

Myron S. Goldman

Lawrence E. Goldman

Ronald Stanford Prince Jr.

In recognizing the humanity of our fellow beings

We pay ourselves the highest tribute.

Thurgood Marshall

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The greatest debt of thanks goes to the men and women interviewed in Thats the Way It Was for their honesty, courage and compassion.

The Missouri Historical Society, now known as the Missouri History Museum, was instrumental in the creation of Thats the Way It Was, specifically Kathy Corbett, Eric Sandweiss, Tim Fox and Candace OConner, who all helped shape this book; with special thanks to Mary Seematter and Emily Jaycox.

George Lipsitz is professor of black and sociology studies at the University of CaliforniaSanta Barbara and chairman of the board of directors of the African American Forum. His insight, generosity and encouragement motivated this book beyond words.

My appreciation to photographers Jennifer Colten, Nate Warren and Maurice Meredith.

I am grateful to Karen Levine Coburn and Frank Hamsher for their valuable suggestions.

My heartfelt thanks go to Walter Lee Hayes, Catharine Weston and Eula Flowers.

Doris Gordon Liberman, my friend and my editor, believed in my work. Her encouragement, her skills in editing and her high standards and knowledge of how to prepare a book for publishing have been indispensable to me. Together we worked with love for the words in this book. I could not have done this without her.

The technical expertise of Granddaughter Tess Prince is evident throughout this work.

To Grandson Tripp Prince, my thanks for listening to these stories like his father did.

My husband, Ronnie, became my editor-in-residence. It is hard to imagine completing this work without his keen comments and suggestions

I thank my children, Patti, Ronnie and Susan, and all my grandchildren for their interest and support.

What a grand journey this has been.

INTRODUCTION

The heart of this book grew out of the words of Marian OFallon Oldham, a civil rights activist and civic leader, during an oral history interview I conducted with her on July 6, 1987, for the exhibit I, Too, Sing America: Black St. Louisans in the 1940s at the Missouri Historical Society. Talking about her early life, Marian described the segregated conditions in downtown St. Louis when she was growing up:

You have to understand that there was no restaurant where we could eat except a black-owned restaurant. There were no theaters, no movie houses where we could go except in the black community. I think there was not a time that I did not go downtown to, lets say, buy a pair of shoes or dress or something that I did not want to go places and do things that were forbidden to me. When you pass an eating counter naturally you want to eatparticularly childrenso I think from a tiny child on, your parents try to shield you from lunch counters, because they know and you know. But there is a hurt and there is a feeling of being less than human.

I think it was marvelous the way our parents went ahead with life and made something out of themselves and their children and had a reasonably healthy existence, despite the real outside world.

As I walked to my car after the interview, my mind was racing with questions. I felt compelled to know what Marian Oldhams words really meant. What was the real outside world? How did the children who lived in that world learn who they were and what were their parents saying to them?

In a telephone conversation with Marian a few years after the oral history interview, I discussed my desire to do an oral history project concerning racism in St. Louis in the twentieth century. Marian replied, I believe in history, but you know what St. Louis needsa place where all kinds of people can come together and get to know each other. I hung up the phone realizing that finding the way to get to know each other is the responsibility of each individual person. My way of doing what Marian hoped for was to create a venuethis oral history projectthat would open a door to the lives of blacks and how they felt about the way it was at that time.

This book is an oral history of thirteen blacks who were born in St. Louis during the first half of the twentieth century. They describe how it was to live in a city that was called the most southern city in the north. Segregation was a way of life. The climate of St. Louis, the lawswritten and unwrittenand the customs of the city governed every aspect of the lives of blacks, including where they were born, where they were allowed to live, their education, their occupations, where they worshipped, where they spent their leisure time and where they were buried.

These oral histories paint a portrait of how parents and children interacted with one another as they faced the pervasiveness of racism in their daily lives and how parents coped with the dilemma of protecting their children from the harsh lessons of that world while at the same time preparing them to live with what they had learned.

This collection also reveals the tradition of respectability and self-respect that runs through the generations of working-class blacks and arms young people with the determination and resilience they need to cope despite the real outside world.

The memories of the thirteen blacks interviewed for this book provide the groundwork for examining the fact that people not only lived this kind of life but also how they felt about the way it was as they learned to negotiate in white urban St. Louis.

The people profiled in this book saw themselves as reflections of how their parents and their own communities defined them: with strong bonds of love and protection, discipline and respect. They also live with the reflection of how the world outside their communities defined themthe prejudice, segregation and discrimination that quietly scarred them. They carry the lessons of their parents along with the pain of feeling unwanted. And each in his or her own way passed those messages on to his or her children, community and the city of St. Louis.

The people I interviewed for this book have become part of my life. The author David Halberstam, in a PBS interview with Charlie Rose, said, You are who you interview; it changes you, enhances you and makes you larger.