LOUIS ARMSTRONG. Copyright 2010 by David Stricklin. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For information, address: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1332 North Halsted Street, Chicago 60642 , a member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

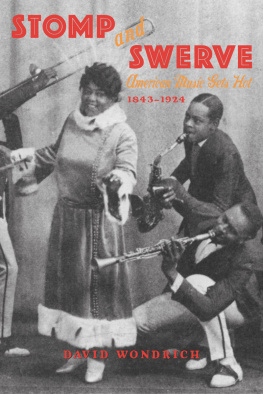

Photographs courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection at the Louisiana State Museum.

Louis Armstrong : the soundtrack of the American experience / David Stricklin.

p. cm. (Library of African-American biography)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-56663-836-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

. Armstrong, Louis, 19011971 . . Jazz musiciansUnited StatesBiography. . African American jazz musiciansBiography. I. Title.

Preface

It will be easier to understand this book if the reader can listen to the music described in these pages. Please see the section titled Recordings at the end of the book and explore the great body of work Louis Armstrong created and helped create, often with some of the most talented and innovative artists in the United States.

I make extensive use in these pages of Armstrongs own writings. He was an enthusiastic letter writer and memoirist with a distinctive, often eloquent writing style. From piece to piece in his writing, however, there is considerable variation in punctuation, spelling, and other usage practices. I quote him verbatim; the reader should not be distracted by the inconsistencies. See the Note on Sources at the end of the book for comments on various theories about Armstrongs writing.

Armstrong called himself Louis (spoken like Lewis), not Louie. He claimed that white people and those who did not know him well called him Louie, though in fairness it should be pointed out that his wives and quite a few of his friends often called him that. I am convinced that he called himself Louis, not Louie, except when singing songs that used the word or otherwise performing from a script written by someone else. As a matter of respect for the great artist, I suggest readers pronounce his name the way he did.

I wish to thank my great former professor and doctoral adviser, Bill C. Malone, for inspiration and guidance over many years of talking about music and books about music and musicians. His excellent work on Southern music has inspired countless students for decades and been a source of illumination to many general readers. One of the greatest of Bills achievements is that his writings pass muster in the scholarly community yet remain accessible to the average reader.

Special thanks to Bruce Raeburn for a sensitive reading of the manuscript and for many helpful suggestions.

I would also like to thank the many people with whom I have had the pleasure of playing music over the years, especially Pat Odom, William Daniel, Landa Sloan, Michael Jay, Gary Atchley, Ronnie Norman, Woody Kemp, Larry Barker, Allen Atkinson, Jay Walters, Warren Nelson, Dennis Keys, David Bates, Kathy Johnson, Vernon and Norman Solomon, Ernie Mills, Edward Hopkins, Bob Gregg, Steve Booth, Steve Barnes, Ken Harrell, Dick Chorley, Daryl Powell, Wes Westmoreland and family, Bill and Bobbie Malone, Russell and Nadiene Van Dyke, Mary Howell, Bob and June Lambert, Pat Flory, Charles Chamberlain, Darla R. and Eddie Durham, Barbara Cook, Michael Frisch, Doug Lambert, John Baird, Kenton Adler, Albert Junior Fulks, Danny Dozier, Micky Rigby, Jim Chlebak, Bill Worthen, Tom Fennell, Herb Rule, Mary McGowan, David Austin, and Chris Stewart.

I also want to pay tribute to my musical family: my late grandfather Meeks Stricklin, great uncles John and Will Benton, and aunt Violet Stricklin, who showed me the first guitar and piano chords I ever learned; my late parents, Betty Stricklin, who owned the first Louis Armstrong recording I ever heard, and Al Stricklin, who played music in a famous western swing band but always considered himself a jazz musician; my daughters, Annie Bowyer Stricklin and Sarah Browder Stricklin, who are truly gifted musicians; my wife, Sally Browder, who has not only taught me a great deal about music but also tolerated my often maddeningly eclectic musical tastes for more than three decades; my mother-in-law, Wilma Browder; my sisters-in-law, Gwen Richardson, Jeanine Johnson, and Peggy Collins, along with Gwens husband, Jesse Richardson, and various musical Browder grandchildren and cousins; my cousin Bill Laatsch; my niece Leigh Anne Willis Bedrich, nephews Jerry and Robert Willis, and musical great nephews and nieces; my brother-in-law Jerry R. Willis; and my sisters, Nancy Stricklin Willis and Judy Stricklin. In one way or another, through their playing and singing, they all have taught me much about music and what it means to people. To my sisters, I dedicate

this book.

Introduction

African Americans have distinguished themselves in a wide variety of endeavors, from science and technology to business and industry, to philanthropy and ethics, to arts and letters. In the twentieth century their influence on the performing arts in the United States was so profound that, it has been said, they helped make popular music the soundtrack of the American experience and American music the preeminent force in the worlds popular culture. Vast numbers of gifted African-American musicians deserve credit for this remarkable turn of events, but a few stand out as true giants: Scott Joplin, Bessie Smith, W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Louis Jordan, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin. This book explores the life of one such giant, Louis Armstrong.

This is not to say that Armstrong was the best or most important musician of them all, though one of his biographers, James Lincoln Collier, calls him the preeminent musical genius of his era. My purpose is to set Armstrong apart as a special representative of these remarkable musicians. The life story of this great instrumentalist, bandleader, and entertainer illustrates much of the black experience in the United States and illuminates the ways popular culture often intersects with political and economic forces in American history.

Armstrong emerged from a most precarious background and triumphed over almost impossible odds. At dozens of moments early in his life, he simply could have disappeared, a promising talent crushed by disadvantage, a remarkable personality consigned to anonymity, a legend never known, a story never told. The fact that he persisted, that he made a life for himself, tells something important about the African-American experience. The fact that he became an international icon tells something important about a remarkable individual. Many observers have called Armstrong a genius; this book will explore his very great talent.

But I will also pay special attention to his identity as an African American and to the ways he triumphed over the mistreatment and disrespect so often given to people very much like him. Many of these people did not have his considerable gifts, but some of them may indeed have had them but simply lost or never enjoyed the opportunities to overcome adversity as Armstrong did, never had the chance to show the nation and the world what remarkable people they were. I often wonder how many Ella Fitzgeralds, how many Sam Cookes, how many Louis Armstrongs lived out their time in virtual anonymity because they never got the breaks, never had anyone take them aside and try to better them, never had the chance to share their gifts with the world. This is the story of someone who did get some breaks, who had someone take him asideseveral people, in factand who got the chance to show what he could do. What he showed and what he shared were his own creations, the expression of his unique and lively sense of freedom. He might have been able to demonstrate that sense in many lines of work, but his story is different and has special power and importance because he expressed it through music.