OTHER BOOKS BY GARY GIDDINS

Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams

The Early Years, 19031940

Celebrating Bird

Faces in the Crowd

Rhythm-a-ning

Riding on a Blue Note

Visions of Jazz

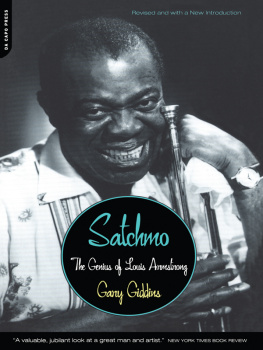

GARY GIDDINS

Satchmo

The Genius of

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Copyright 1988 by Gary Giddins

Introduction copyright 2001 by Gary Giddins

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN-10: 0-306-81013-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-306-81013-8

eBook ISBN: 9780786731459

Original edition: Produced by Toby Byron/Multiprises

First Da Capo Press text edition, January 2001

The text of this book also appears in slightly different form in an illustrated edition by the same author.

Text design by Jeff Williams

Set in 11-point Janson Text by Perseus Publishing Services

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

http://www.dacapopress.com

Responding in 1949 to a Blindfold Test in which he was askedto rate unidentified records with one to five stars, Louis Armstrongsaid:

I couldnt give anything less than two stars. You want to know why? Well, theres a story about the sisters who were talking about the pastor, and only one sister could appreciate the pastor. She said, If hes good, I can look through him and see Jesus. If hes bad, I can look over him and see Jesus. Thats the way I feel about music.

I loved and respected Louis Armstrong. He was born poor, died rich, and never hurt anyone on the way.

Duke Ellington

The Abbot gazed at the boy who stood before him. He had intended to scold him, but as he looked at him, his expression sweetened. Why did you stop, my child? he asked. You abandoned the vision in the middle. One mustnt do that. Hes a prophet, and prophets must be revered.

Nikos Kazantzakis

To the memory of Louis Armstrong

And to my family

Alice and Bill, Donna and Paul,

Lee and Jennifer, Helen and Norman and Ronnie,

and the Green-Eyed Wonder.

And to the family of jazz, particularly the

illegal Prague Jazz Section

its leaders Karel Srp and Vladimir Kouril,

their fellow defendants Vlastimil Drda, Milos Drda,

Csmir Hunst, Tomas Krivanek, and Josef Skalnik,

and their countless supporters

whose courage in the face of lunatic persecution

reminds the world that Louis Armstrongs legacy

is an art of unconditional freedom and that

oppressors of every stripe will always fear it.

A Note to the

New Edition

When the original edition of this book appeared in 1988, the argument I made in defense of Louis Armstrongs achievement as an entertainer was controversial. At that time, the idea that Armstrongs genius peaked and virtually ended with his 1920s records (the Hot 5s and Hot 7s) was fairly widespread, as was the hapless if not embarrassed critical response to his flair for comedy and devotion to his audience. Times change, and nothing gratifies me more than the realization that if I were writing this book today, I could take a lot of my old position for granted, and move on.

An illuminating study could be made of Armstrong criticism during his life and after. I remember when Dan Morgenstern was a lonely voice, obliged to defend not only Armstrongs later work, but the 1930s big band masterworks that are now routinely hailed as classics. The perspective keeps changing. Today, young listeners, who know nothing of the old battles, are more inclined to accept Armstrong whole, and are often surprised that battles were ever waged. His singing of pop songs is now experienced as an essential part of his achievement, to a degree that was not true even during the years when his vocal records ranked high on the charts. Or was it because they were so popular that critics dismissed them as secondary diversions?

I chose the Kazantzakis epigram (from The Last Temptation ofChrist) to make the point that Louis Armstrong was a prophet and that to be completely understood and appreciated, his vision ought to be pursued to its end. Not everything he recorded is wonderful; like Homer, Armstrong nodded. Most of his legacy, however, is quite wonderful, and the delights will be found throughout the trajectory of his career. His genius can be relished in Hello, Dolly! as well as in West End Blues. But there I go again, making an argument I just said no longer needed to be made. In truth, I continue to find myself going deeper into the vision.

For example, when Armstrongs 1966 recording of Mame was first released, I thought of it as amiable pop fluff, an obvious attempt to cash in on the Hello, Dolly! phenomenon, only without a trumpet solo. Having rediscovered it a couple of years ago, I now treasure it as a singular example of his alchemical powers and outsize musical personality. The song is so undistinguished one can scarcely imagine another singer attempting it. Yet Armstrong transforms it into something rich, expressive, exultantly swingingcan anyone be unmoved by the rapturous, room-filling, trombonelike melisma he consistently applies to the title name? Bing Crosby once asked, Do you realize that the greatest pop singer in the world that ever was and ever will be forever and ever is Louis Armstrong? He explained: Its so simple. When he sings a sad song you feel like crying, when he sings a happy song you feel like laughing. What the hell else is there with pop singing?

This book, like most books and articles about him, attempts to define Armstrongs influence, place, and historical stature. Yet at some point, that approach must give way to sheer pleasure, to a critical evaluation that takes the music on its own. We love Bach for Bach, not for his historical role in the development of Western culture. I think of Armstrong as Americas Bach not because of his analogous place in the development of American culture, but because he imparts a similar joy, love, and ecstasythe godly intimation that the world is much greater than we can ever imagine except through the visions of those geniuses, those prophets, who see farther than we can and proclaim the truth with the certainty of their art.

G. G.

October 2000

Preface

Some books and articles call him Daniel Louis Armstrong. No one seems to know where the Daniel came from. Armstrong said it was not part of his name, and his baptismal certificate backs him up. You can start a fight over how he was addressed by friends. The Louis faction (Hello, Dolly, this is Louissss, Dolly, the man sang) can get downright rude about those who pronounce it Louie. He wasnt French, they point out. But many friends and at least two wives called him both. The safest and by far the most common form of address was Pops, which is how he addressed everyone elsethough in letters he would refer to male friends as my boy and to himself as your boy. As a kid with a large trumpet players mouth, he earned many nicknames, including Dippermouth or Dip, Gatemouth or Gate, and Satchelmouth or Satch. The last, unwittingly corrupted by a British journalist (Percy Brooks), survived as Satchmo. Insiders will tell you that no one ever called him that. No one but the man himself, who loved the name, and a hundred million fans who loved him.