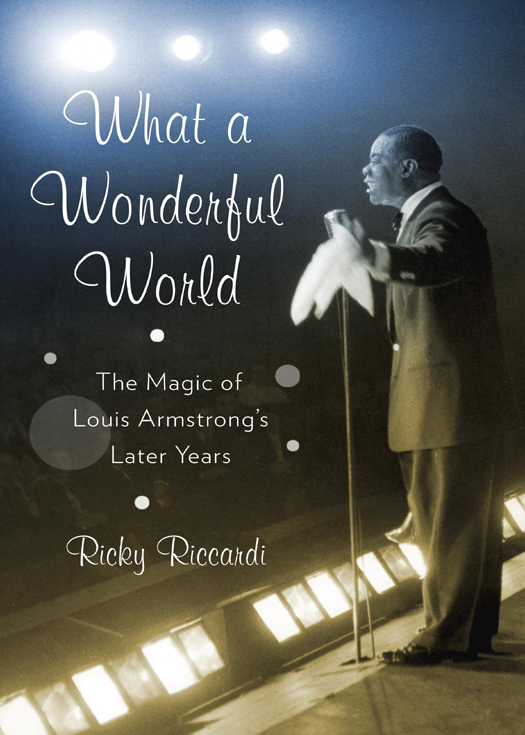

Copyright 2011 by Ricky Riccardi

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon

Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

All permissions to reprint previously published material can be

found immediately following the index.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Riccardi, Ricky, [date]

What a wonderful world : the magic of Louis Armstrongs later years /

Ricky Riccardi.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37923-8

1. Armstrong, Louis, 19011971. 2. Jazz musiciansUnited States

Biography. I. Title.

ML419.A75R47 2011 781.65092dc22 [B] 2010046541

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket image courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum

Jacket design by Brian Barth

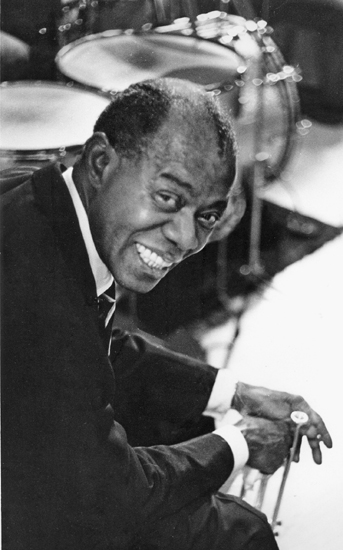

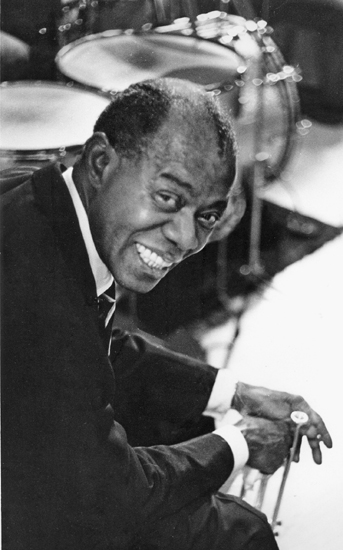

Slowing down in Philadelphia in June 1968,

a thinned-down and tired Armstrong managed to still

flash his smile at Jack Bradleys camera. Two months later,

kidney trouble would force Armstrong to spend nearly

a year and a half recovering at home.

v3.1_r1

For my parents, without whom

I never would have started this book

and for Margaret and Ella, without whom

I never could have finished.

Ive been thinking a whole lot of things. Through the years, Ive noticed you take, not only critics, you take the man on the street or some cat that think he knows a whole lot about music and records and things, theyll come up and say, Man, youre doing all right but I remember when you was really blowing that horn. And Ill look at him and say, Well, solid, Gate, but he dont realize that Im playing better now than Ive ever played in my life.

LOUIS ARMSTRONG, 1956

Contents

14 From the Dukes of Dixieland to Dave Brubeck,

19601963

Introduction

A PACKED THEATER IN CHICAGO is in attendance to cheer on one of the most beloved musicians in town, Louis Armstrong. Armstrong walks to center stage, a devilish grin on his face; his eyes widen. He picks up his trumpet and begins blowing a tune from a current Broadway show. The audience goes wild at the mere sound of his horn. Armstrong creates a dazzling solo on the popular song, eliciting shouts from the crowd each time he hits a high note. As he finishes, he launches into a novelty number showcasing his talent as a singer and then transitions to a swinging scat interlude, his eyes closed. As he mugs ever so slightly, the crowd applauds his vocal inventiveness.

Armstrong disappears offstage and returns in tails, a pair of glasses, and a funny hat. Impersonating a preacher, he tells some of Bert Williamss finest vaudeville jokes and delivers a satrical monologue, before resuming on his trumpet. The band plays Sugar Foot Stompa good old oneand Armstrong swings out with chorus after chorus of blues playing. When he finishes, he bows and grins, closes his eyes, and unleashes a smile to end all smiles.

Was this 1957, or 1967the latter part of Armstrongs career when he was derided by some as an Uncle Tom? No, the year was 1927. The Broadway number was Nol Cowards Poor Little Rich Girl, one of Armstrongs big features with Erskine Tates orchestra at the Vendome Theatre. The novelty song he scatted was Heebie Jeebies and the preacher routine harked back to his childhood in New Orleans, where he won applause for impersonations and sermons at the local church. A 1927 review found among Armstrongs personal scrapbooks read, Erskine Tates orchestra at the Vendome Theatre last week was a wow. Louis Armstrong, who is one of [Heebie Jeebies] pet writers, led the members of the popular orchestra in a prayer with his cornet. During his offering he wore a high silk hat, frocktail coat and smoked glasses. The fans are still giggling over the act as it was far the most amusing one ever seen here.

Louis Armstrong won audiences over with showmanship, laughter, and sublime music, starting as early as 1927. It is the Armstrong of that year who is usually made out to be the serious artist, celebrated for the groundbreaking Hot Five and Hot Sevenrecordings that announced the singularity of jazz as a true American art form. So it was no surprise that Christopher Porterfields 2006 Time magazine review of Armstrongs 1920s work exclaimed, Forget the Satchmo who sang and mugged his way through his later decades, wonderfully entertaining as he was. This is Armstrong the force of natureexuberant, inspired, irresistible.

The truth is, Louis Armstrong was a force of nature from the time he first picked up his horn as a teenager until the day he died in 1971. Yet the myth of the two Armstongs continues: the young serious artist and the old entertainer. In fact, Armstrong had always been a master showman. Every aspect of his character, including love of entertaining, was formed during his childhood in New Orleans, singing and scatting in a vocal quartet before even learning to play the cornet. When he joined the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in New York in 1924, Henderson only grudgingly allowed Armstrongs Bert Williams vaudeville routines on stage, fearing they were too rough around the edges for the predominantly upscale audience. This rankled Armstrong for years: Yeah, but Fletcher didnt dig me like Joe Oliver, Armstrong recalled in a 1960 interview. He had a million-dollar talent in his band and he never thought enough to let me sing or nothing. Hed go hire a singer, that lived up in Harlem, that night for the recording the next day, who didnt even know the song. And Id say, Well, let me sing. Nooo, NOOOO! All he had was the trumpet in mind. And thats where he missed the boat. In those days, all Fletcher had to do was keep in his band the things that Im doing now.

Even at age twenty-four, Armstrong was confident of his million-dollar talent to sing and entertain as well as play the trumpet. When he joined Erskine Tates symphony orchestra in Chicago in 1925, Armstrongs popularity skyrocketed, leading to the vaunted Hot Five recordings for the Okeh label. The Hot Fives and the later Hot Sevens brim with funny bits, though the humorous songs are usually given short shrift.

This dismissal of Armstrongs later years can be traced back to Gunther Schullers 1967 work Early Jazz, which systematically solidified the jazz canon of the 1920s. With a background in classical music, Schuller had no patience for Armstrongs comedic tendencies and instead focused chiefly on his trumpet playing. Subsequent jazz histories followed Schullers lead, rightfully praising tunes like West End Blues and Potato Head Blues, but at the expense of less serious works such as Irish Black Bottom or Thats When Ill Come Back to You. Twenty years later, Schuller followed Early Jazz with The Swing Era, in which he continued to praise Armstrongs trumpet playing, but grew increasingly weary of his showmanship. By the time he addressed Armstrongs later years, Schuller was despondent. But the end was not what it should have been, he wrote before suggesting that as Americas unofficial ambassador to the world, this country should have provided him an honorary pension to live out his life in dignity, performing as and when he might, but without the need to scratch out a living as a good-natured buffoon, singing Blueberry Hill and What a Wonderful World night after night.