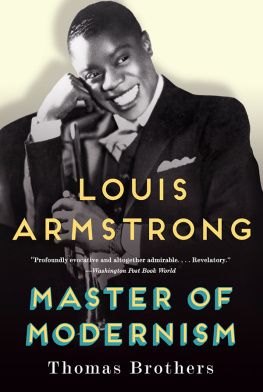

LOUIS

Master of Modernism

ARMSTRONG

Thomas Brothers

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

FOR

Olly Wilson,

Samuel A. Floyd Jr.,

AND

T. J. Anderson

CONTENTS

Louis Armstrong produced, during the glory years of the mid-1920s through the early 1930s, a musical legacy of tremendous richness and joy. Armstrong, to our great fortune, was also prolific in documenting his life through letters, interviews, and memoirs. To this material we may add autobiographies of and interviews with his contemporaries, as well as a vibrant collection of archival sources, including African-American newspapers of the day, some rare and some now available for web-based searching. The result is an extremely rich body of documentary evidence that allows us to view Armstrong, his life and his musical legacy, from the inside.

To draw attention to the details of this legacy, I sometimes refer to specific timings in his recordings, indicated in parentheses (e.g., CD: 1:10). A brief discography of reissued CDs is published in the back for those who wish to listen along as they read. And since one of the aims of this book is to place Armstrongs music within a broader historical context. I also include a detailed bibliography of my sources, divided into two parts, one for archival material and the other for general publications. The former are distinguished by an abbreviation for the archive where the document is held, inserted after the author and before the date (e.g., Keppard HJA 1957).

The book provides two types of notes. Superscript numbers in the text alert the reader to explanatory material that appears in the Endnotes section in the back of the book. The Source Notes include brief citations, keyed to the main body of the book by page number and key phrase.

Acknowledgments

Compelled to make frequent research trips to New York City, I remain grateful for the hospitality of Giuseppe Gerbino, Krin and Paula Gabbard, and Jeff Taylor; I am equally indebted to Lewis Erenberg and Susan Hirsh in Chicago. At Duke, Roman Testroet, Karen Cook, Jason Heilman, and Dan Ruccia provided excellent assistance. No less important has been the archival help of Michael Cogswell (Louis Armstrong House Museum), Bruce Boyd Raeburn (Hogan Jazz Archive), Alfred Lemmon (Williams Research Center), Dan Morgenstern (Institute of Jazz Studies), Kelly Martin (University of Missouri, Kansas City), Deborah Gillaspie (University of Chicago), Linda Evans (Chicago History Museum), and David Sager (Library of Congress). Dukes library staffLaura Williams, Tom Moore, and staff at the Music Library and the staff at Perkins, Lilly, and Interlibrary Loanhas supported my work with precision and care for many years. Likewise I have constantly relied on Jos Willemss amazing All of Me: The Complete Discography of Louis Armstrong ; my thanks to Jim Farrington for introducing me to it. In William Howland Kenneys indispensable Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History , a splendid field of research was opened up for me. Now that it is gone, the amazing achievement that was Redhotjazz seems more special than ever. My thanks to Steven Lasker, who supplied me with material he collected on Armstrongs California year, and to Chris Albertson and Ron LHerault for photos. Two leading specialists in jazz of this period, Bruce Boyd Raeburn and Brian Harker, shared their knowledge and offered help at a number of turns. Without a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, combined with a Deans leave from Duke University, this book would not have been possible. Likewise without the support of my family, Leo and Roger, and especially Tekla, whose patience with my work habits has been immense. Maribeth Anderson Payne provided, once again, invaluable advice and editing, such as no musicologist can take for granted. At Norton, I am also grateful for the thorough and professional help of Michael Fauver and Harry Haskell. This book is dedicated to Olly Wilson, Samuel A. Floyd Jr., and T. J. Anderson, three musicians who have offered me so much support over the years, insights and mentoring that got me started, and encouragement and inspiration that have kept me going.

He was just an ordinary-extraordinary man.

Doc Cheatham

October 1931, Memphis, Tennessee

Louis Armstrong and His Orchestra are performing at the Peabody Hotel, giving local jazz fans a chance to finally see and hear in person the singer-cornetist whose records they have been collecting and whose radio broadcasts they have been tuning in to. Master of Modernism and Creator of His Own Song Style is how he is billed, and no one dismisses it as mere marketing hype. Few performers, black or white, are more exciting or innovative. Armstrong has been packing them in on this tour of the South, in city after city, segregated white hall after segregated black hall, with an occasional thrill of mixed patronage now and then, carefully guarded by the police.

Everyone in the audience is white, the ten musicians black. The modern master himself is very blackwhich is to say, first, that he has very dark skin, and second, that he is culturally very black. He does not disguise this cultural allegiance. To the contrary, he has found ways to glorify it while reaping tremendous financial rewards.

Armstrong announces that he would like to dedicate the next song to the Memphis Police Department. Turning to the band, he sets the tempo and they are off with their arrangement of Ill Be Glad When Youre Dead You Rascal You .

Trombonist Preston Jackson reacts with a nervous jolt, and with good reason. Ill be glad when youre dead, you rascal you! Armstrong sings. Ill be tickled to death when you leave this earth, you dog! he grins, shucks, and jives. Hes dedicating this song to the Memphis police? Not a bunch known for their sense of humor, and many are members of the Ku Klux Klan. What saves the moment is that while the band knows the words, the audience cannot easily make them out. For part of Armstrongs modern song style is a weird way of mixing words and nonsense syllables, sometimes blurring the line between the two, just as the melody he sings is part original tune, part radical transformation of that tune, and part free invention. The policemen come up afterwards to thank Armstrong, and Jackson relaxes. No other band coming through town has ever honored them like this, they tell him.

Some of the musicians were reluctant to take this southern tour. They would have agreed with the New Orleanian banjo player Danny Barker, who explained that Chicago was considered to be the safest place near New Orleans... getting off a Chicago-bound train... before it reached its destination was like a ships captain, in mid-ocean, putting someone on a small raft to drift without provisions. But this is the Depression, which causes people to do things they would not do under normal circumstances.

The relationship of Armstrongs band to the Memphis police was already loaded with tension, for the night before the Peabody Hotel gig they had all been thrown in jail. Their crime: Armstrong was discovered sitting next to his white managers white wife on the chartered bus, the two of them talking over business. Why didnt you shoot him in the leg? one officer demanded from his colleague when he witnessed this provocative scene. On stage, Armstrong displays a persona that is alternately confident, even cocky, with his powerful trumpet virtuosity, and seductive, with his innovative style of singing ballads. Artistically, he is at the top of his game, yet he is crippled by a society that seethes with brutally racist ideologies, laws, and practices.

And thus it was that one of the most important musicians of the twentieth century made his living in 1931. Race was the ever-present elephant in the room. It affected Armstrong every day and every moment of his life, on different levels simultaneously. Today we live in a country that yearns for postracial harmony, which makes it comfortable to ignore this distant reality and concentrate instead on the astonishing splendor of his music.

Next page