Contents

Guide

Page List

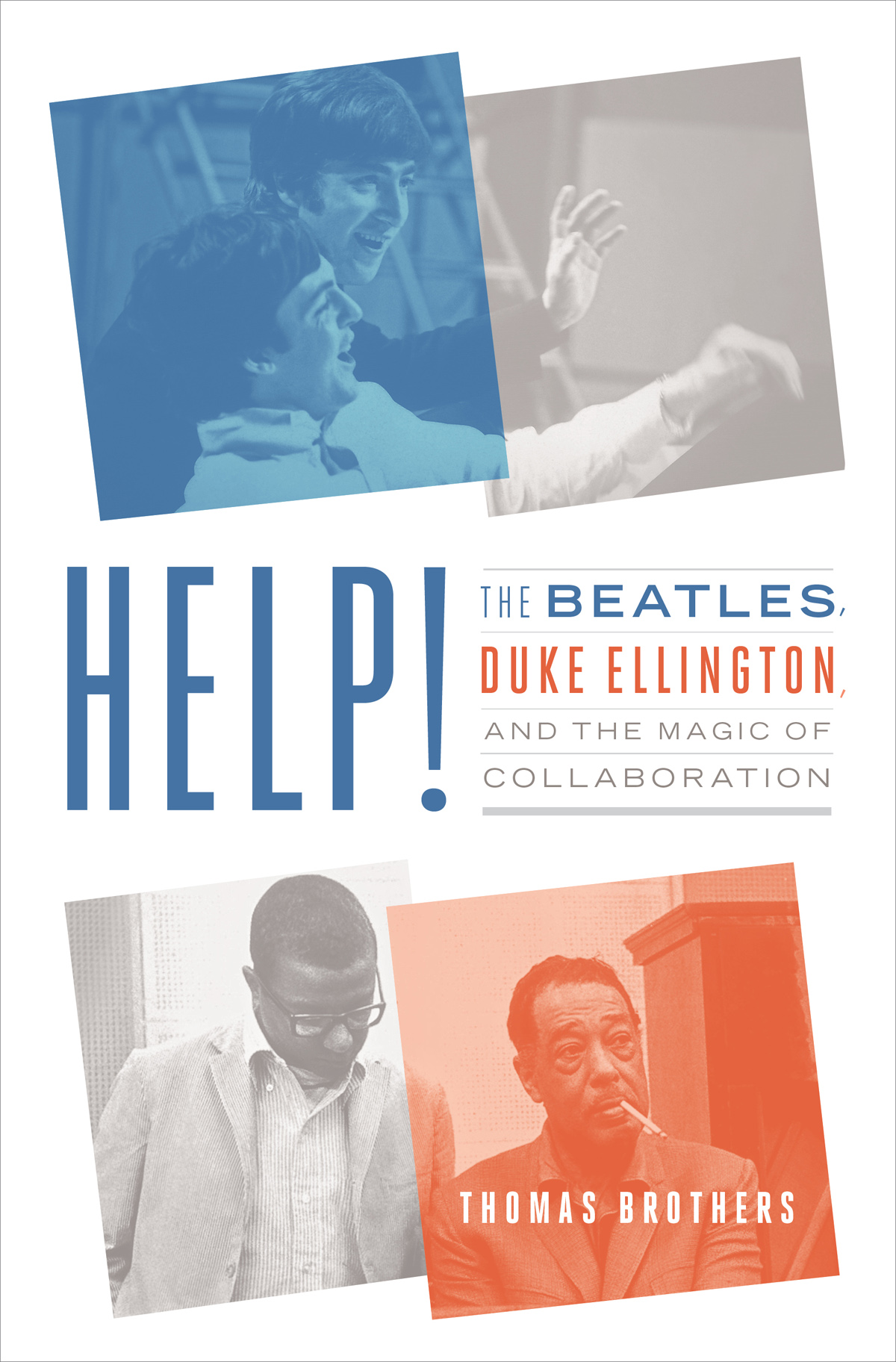

HELP!

The Beatles, Duke Ellington, and the Magic of Collaboration

Thomas Brothers

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Also by Thomas Brothers

Louis Armstrongs New Orleans (2006)

Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism (2014)

a thing as magic,

and the Beatles were magic.

PAUL McCARTNEY

The Beatles, like Duke Ellington,

are unclassifiable musicians.

LILLIAN ROSS,THE NEW YORKER(JUNE 24, 1967)

For Tekla

CONTENTS

IN THE SPRING OF 1863, journalist Charles Carleton Coffin traveled from Boston to South Carolina. His intention was to file a report on the imminent recapture of Fort Sumter by the Union Army. Though that event took longer to unfold than he and his fellow Yankees had expected, he took the opportunity of his extended stay to observe religious services of recently freed slaves. After the war he wrote an account of what he saw.

At the African Baptist Church in Port Royal, near Beaufort, Coffin was pleased to hear the hymn St. Martins, composed by William Tansur. The singers took considerable liberty with the melody, adding, as it, crooks, turns, slurs, and appoggiaturas not to be found in any printed copy. At the end of the formal service they transitioned into an even stranger phase, with benches pushed to the walls and everyone moving around in a display of spiritual rapture. They shuffled in jerking motions, clapping their hands and stamping their feet, with impressive precision and vigorous syncopation. As they rotated in a circle, their voices louder and louder, they seemed to repeat the same song again and again. Unlike the hymn from Tansur, Coffin did not recognize this song. The leader of the group fixed his eyes in a trancelike stare, prompting swelling tides of emotion. When the shouters eventually tired they simply stopped for a few minutes before starting another tune. Coffin was amazed by the fluid and independent motion of legs, arms, head, body, and hands, as if every joint hung on wires.

This report of a musical vision radically different from anything the author had known in New England is matched and extended by others, scattered in time and place throughout the South. The most common name the participants gave their circle ritual was ring shout. Daniel Alexander Payne, an African American preacher and one of the founders of Wilberforce University, admonished former slaves to forget all about the ring shout and adopt more dignified, Eurocentric forms of worship. But there was tremendous momentum in the opposite direction. Ring shout observers described strained vocal production indicating heightened emotions, precise synchrony between body and music, bending pitch, blue notes, hard initial attack, and the fixed and variable format for organizing rhythm. Today, the entire package is familiar through the recorded history of jazz, rock, gospel, blues, soul, and funk.

The ring shout combined emotional release with spiritual fulfillment, and it included another dimension that was just as important: the ritual was deeply communal. One of the great, central truths of musics role in the African diaspora was its power to bring people together. Which sister supplied the slurs, which brother the hooks, which the bends, which the growls? The practice was designed to make it easy for each person to find his or her place in a collective whole. , working in the 1970s with the Ewe people of Ghana, observed that musics explicit purpose, in the various ways it might be defined by Africans, is, essentially, socialization. That purpose and the techniques for achieving it were fully transmitted to the New World, where people from different parts of Africa came together and discovered what they had in common. In spite of vicious annihilation of social networksor because of thatthe community-building role of music only grew stronger.

Interaction among those present mattered more than a precise rendition of Tansurs hymn or any hymn. The ring shout was open-ended and accommodating. Tunes could be reduced to simple fragmentsriffs, as they are called in jazz. Participants standing outside the inner circle formed the of the base made it easy to add claps, stamps, crooks, portamentos, delicate variations, syncopations, accents, and ecstatic outbursts without losing a sense of continuity and togetherness. It made it easy to sonically and visually connect with one another.

There was plenty of room for creativity. Basers could change harmonies if they felt like it, while shouters added effects of , who had been enslaved in Kentucky, remembered how all of them could sing and keep time to music, improvise extra little parts to a melody already known, or make up melodies of their own. The singers jumped through different vocal registers and they shifted from words to vocalization, hushed murmurs, soft croons, assertive urgings, and forceful confessions.

Leaders had a knack for inventing. There was some allegiance to tunes that had been carried over from Africa and some borrowing from white hymnody, but it was more fun to get in touch with the Holy Spirit and watch a new spiritual unfold on the spot. The base alternated with the leader to give him or her time to think of what was coming next. it up and keep at it, and keep a-adding to it, and then it would be a spiritual, as another former slave remembered. Musicians in Duke Ellingtons Orchestra and the Beatles used similar words to describe how they generated material.

It was all done without musical notation, of course, a key for producing results so dramatically different from scripted music. that ring-shout music was as impossible to place on score as the singing of birds. Nonliteracy, perceived as a lack by outsiders, was the starting point for the open-ended harvest of communal synergy. What appeared to be a disadvantage produced a distinctive field of musical creativity.

It may seem odd to join together Duke Ellingtons Orchestra and the Beatles in a single study, and odder still to begin the account in Port Royal, South Carolina, in 1863. Ellingtons upwardly mobile childhood in Washington, D.C., did not expose him to the ring shout or anything close to it. His parents would have been more sympathetic to the assimilative agenda of Daniel Alexander Payne. The Beatles were even more remote, across the Atlantic Ocean and across the boundary of race, almost a century later.