USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Gotham Books and the skyscraper logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

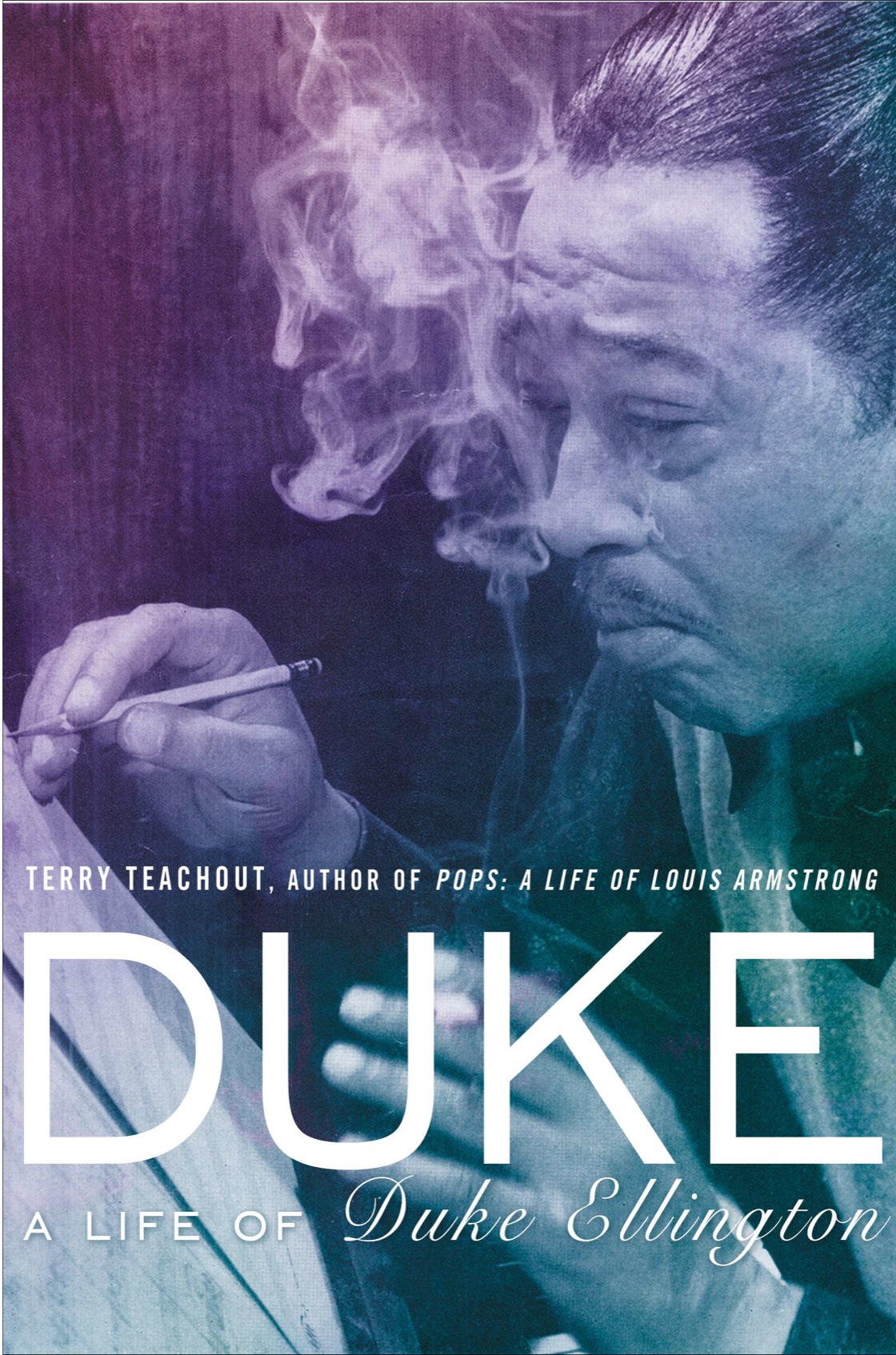

Teachout, Terry.

Duke : a life of Duke Ellington / Terry Teachout.

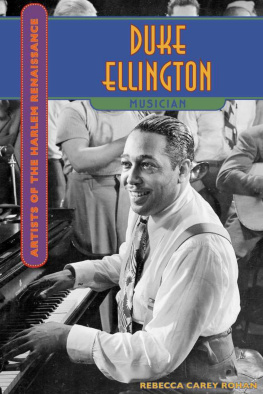

1. Ellington, Duke, 1899-1974. 2. Jazz musiciansUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

CONTENTS

Fortunate Son, 18991917

Becoming a Professional, 19171926

With Irving Mills, 19261927

At the Cotton Club, 19271929

Becoming a Genius, 19291930

Becoming a Star, 19311933

On the Road, 19331936

Diminuendo in Blue, 19361939

With Billy Strayhorn, 19381939

The Blanton-Webster Band, 19391940

Jump for Joy, 19411942

Carnegie Hall, 19421946

Into the Wilderness, 19461955

Crescendo in Blue, 19551960

Apotheosis, 19601967

Alone in a Crowd, 19671974

Fifty Key Recordings by Duke Ellington

To Mrs. T, who was never in doubt

There is one very good thing to be said of posterity,

and this is that it turns a blind eye on the defects of greatness.

W. Somerset Maugham

We wear the mask that grins and lies.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

PROLOGUE

I WANT TO TELL AMERICA

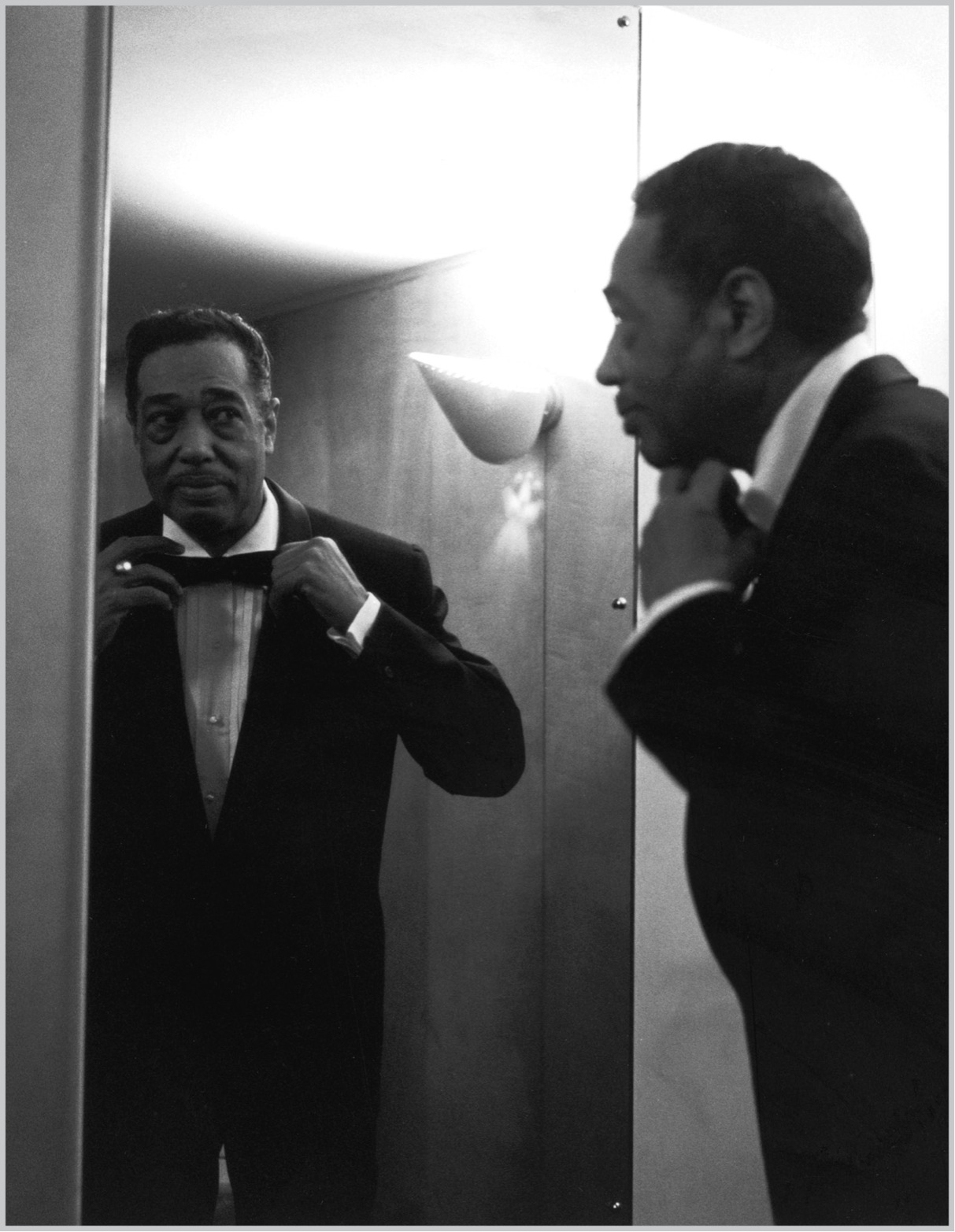

H E WAS THE most chronic of procrastinators, a man who never did today what he could put off until next month, or next year. He left letters unanswered, contracts unsigned, watches unworn, and longtime companions unwed, and the only thing harder than getting him out of bed in the afternoon was getting him to finish writing a new piece of music in time for the premiere. I dont need time, he liked to say. What I need is a deadline! Nothing but an immovable deadline could spur Duke Ellington to decisive action, though once he set to work in earnest, it was with a speed and self-assurance that amazed all who beheld it. At the end of his life, he left behind some seventeen hundredodd compositions, a number that is hard to square with the memories of his collaborators, who rarely failed at one time or another to be frustrated by his dilatory ways. That was fine with him. He knew what he needed in order to create, and as far as he was concerned, nothing and no one else mattered. As long as something is unfinished, he told Louis Armstrong, theres always that little feeling of insecurity. And a feeling of insecurity is absolutely necessary unless youre so rich that it doesnt matter. Few of his pronouncements can be taken at face valuehe was never in the habit of telling anyone, even those who supposed themselves to be his friends, what he really thoughtbut this one has the ring of truth. He wants life and music to be in a state of becoming, said the trumpeter Clark Terry, one of the many stars of the band that Ellington led from 1924 until his death a half century later. He doesnt even like to write definitive endings to a piece.

Whether it was true or merely one of his rationalizations for doing whatever he wanted to do whenever he wanted to do it, Ellington lived by those words. Time and again he found himself bumping up against deadlines because of his reluctance to finish what he had started. More often than not his talent got him out of the holes he dug for himself, and when it didnt, he counted on his charm to see him through. Duke drew people to him like flies to sugar, said Sonny Greer, one of his oldest friends and his drummer for three decades. He was well aware of how charismatic he was, and used his powers without scruple whenever he thought it necessary. Once in a while, though, he cut it too close for comfort, and in the frantic days and nights leading up to his Carnegie Hall debut on January 23, 1943, some of his colleagues began to wonder whether Harlems Aristocrat of Jazz (as his publicists dubbed him) had finally outsmarted himself.

As early as 1930 Ellington was telling reporters of his plans to compose a piece of program music about the black experience. My African Suite, he called it. It will be in five parts, starting in Africa and ending with the history of the American Negro. Sometimes he described it as a multimovement instrumental work, sometimes as an opera, but either way he made it sound as if the ink were wet on the page, and his serpentine way with words never failed to hypnotize even the most suspicious of interviewers into assuming that the curtain was about to go up. In 1933 Hannen Swaffer, an English columnist, published an interview in which Ellington spoke of the unwritten work so evocatively that you could all but hear it playing in the background:

I am expressing in sound the old days in the jungle, the cruel journey across the sea and the despair of the landing, and then the days of slavery. I trace the growth of a new spiritual quality and then the days in Harlem and the cities of the [United] States. Then I try to go forward a thousand years. I seek to express the future when, emancipated and transformed, the Negro takes his place, a free being, among the peoples of the world.

Swaffer was no friend of jazz, or of blackshe had once compared Louis Armstrong to a gorillabut he bought Ellingtons story hook, line, and sinker. All this was said with a quietness of dignity, he assured his readers. I heard, almost, a whisper of prophecy.

Many more journalists would prove as willing to take Ellington at his oft-repeated word. That same year Fortune told its readers that he was writing a suite in five parts... With this suite in his repertoire, Ellington may some day make his Carnegie Hall debut. In 1938