Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016.

Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS16CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rohan, Rebecca Carey, 1967- author.

Title: Duke Ellington : musician / Rebecca Carey Rohan.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, 2017. |

Series: Artists of the Harlem Renaissance | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015035470 | ISBN 9781502610607 (library bound) |

ISBN 9781502610614 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ellington, Duke, 1899-1974. | Jazz musicians-United States--Biography.

Classification: LCC ML410.E44 R64 2016 | DDC 781.65092-dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015035470

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Elizabeth Schmermund Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot Designer: Stephanie Flecha Senior Production Manager: Jennifer Ryder-Talbot Production Editor: Renni Johnson Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

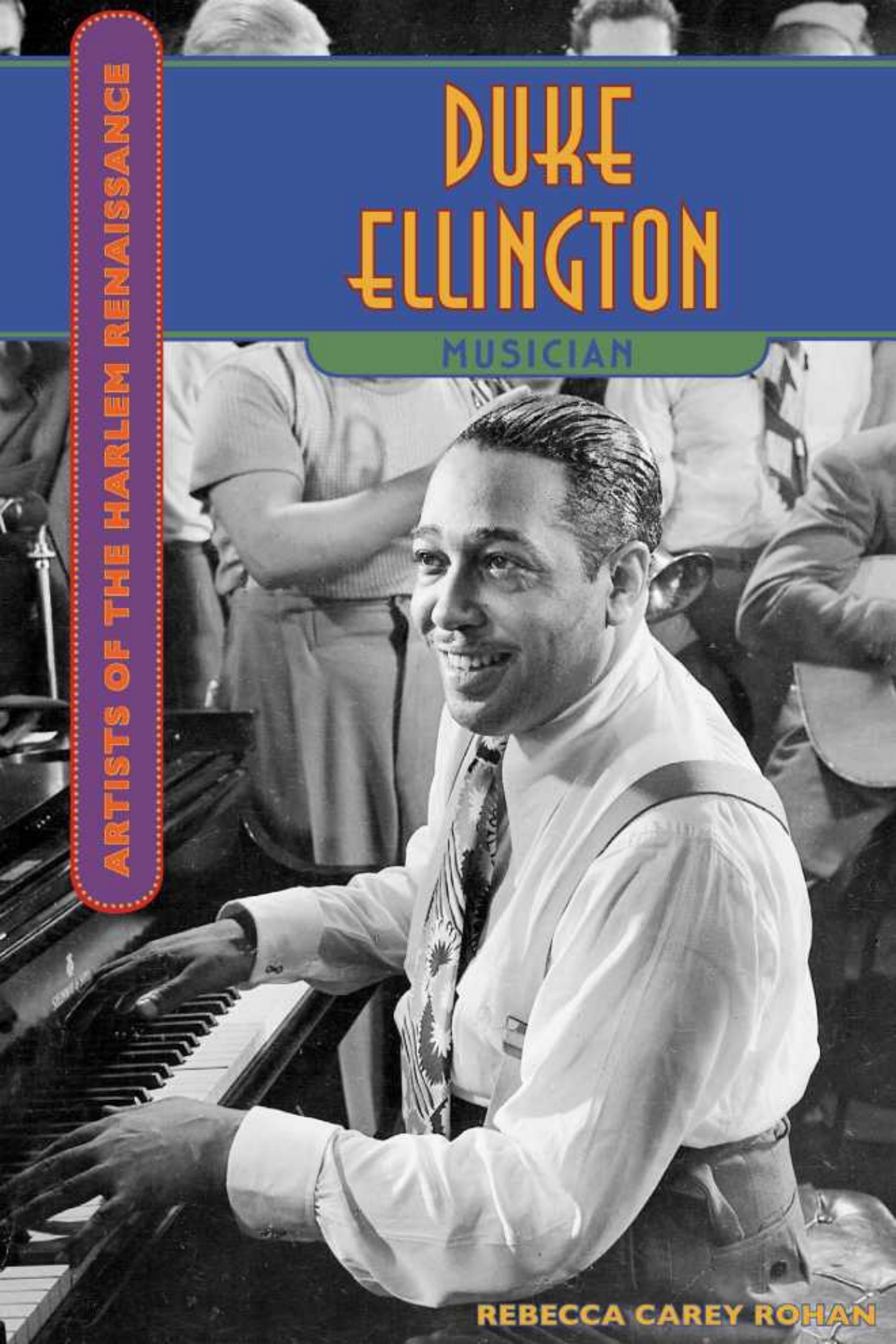

Gjon Mili/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, cover; Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images, back cover; Franz Hubmann/Imagno/Getty Images, 5; Thomas D. Mcavoy/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 6; Library of Congress, 12-13, PF(bygone1)/Alamy Reportage Archivalfimage, 16; Henry P. Whitehead Collection/Anacostia Community Museum, 18; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division/ Regina Andrews photograph collection/NYPL, 20; Duke Ellington Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History/SIRIS, 22, 62, 98-99; Jamees Kriegsmann/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, 24; Gilles Petard/Redferns, 28; Eliot Elisofon/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 31; Bridgeman Images, 33; Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, 37; Paul Hoeffler/Redferns, 38-39; Fulton-Larson Company, Chicago/ File:Great Northern pullman car in day mode 1926.JPG/Wikimedia Commons, 42; Daniel Dempster Photography Alamy, 44; Smithsonian Institution, 47; Everett Collection Historical Alamy, 50; Album/Newscom, 52, 69; Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 56; AP Photo, 58; National Archives/File:Richard M. Nixon presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Duke Ellington. - NARA - 194289.tif/Wikimedia Commons, 61; Michael Ochs Archives/ Getty Images, 65; Gilles Petard/Redferns, 74; Walter McBride/WireImage, 76; PhotoQuest/Getty Images, 78; OldMagazineArticles.com, 83; Bill Wagg/Redferns/Getty Images, 85; Charles 'Teenie' Harris/Carnegie Museum of Art/Getty Images, 87; AP Photo/John Lent, 91; Everett Collection Historical Alamy, 94; Don Emmert/AFP/Getty Images, 96; Jack Mitchell/Getty Images, 103; Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images, 107; Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, 109; Citizen of the Planet/Alamy, 111; Walter McBride/WireImage, 113.

Part I: The Life of Duke Ellington

Chapter1

Chapter2

Chapter3

Part II: The Work of Duke Ellington

Chapter4

Chapter5

Chapter6

Opposite: The police enforced segregation of whites and African Americans at this concert at the Lincoln Memorial.

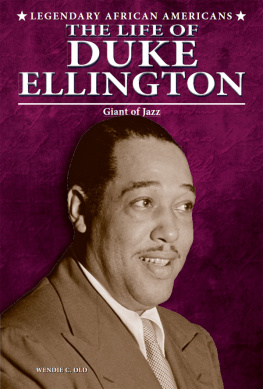

C omposer. Bandleader. Songwriter. Musician. Edward Duke Ellington was all of those things, yet he accomplished so much more. While he started his career as a pianist, he became the leader of a jazz orchestrathe only major leader of a jazz orchestra who also composed most of the music he played. He was instrumental in spreading the popularity of the ragtime sound and jazz music, yet he refused to call himself a jazz musician. He called his work Negro music, American music, or the music of my people.

And he was right: jazz, as an art form, was invented by Americans. It originated in New Orleans, Louisiana, a city with a distinct culture that was a melting pot of African Americans, Native Americans, and families of European descent. Jazz music sprang from the musical traditions of both Africa and Europe. Duke Ellington took those traditions and made them his own.

Yet, his rise to fame is not the stereotypical rags to riches story, nor was his genius discovered at an early age. Edward Kennedy Ellington was born in Washington, DC, in 1899, into a stable, loving family. He was the first child of Daisy and James Ellington, and also their only child for the first sixteen years of his life, until his sister Ruth was born in 1915. He would be the first to admit that he was a spoiled, coddled child who was raised to feel that he was special.

His mother, Daisy Kennedy Ellington, was not only a beauty; she was an educated woman. She had completed high school, which was rare for a black woman at that time. Her father was a policeman who knew many important Washingtonians. She supposedly had a white grandfather and a Native American grandmother. Daisy taught her son Edward spirituality and discipline.

His father, James Edward Ellington, worked for a time as a butler and house manager for a well-known white physician, and he occasionally worked catering jobs at the White House. He taught his son how to be a refined young gentleman, based on what he had observed on the job. He was also outgoing, witty, and a practiced flirttraits he passed on to his son.

At the time of Edwards birth, Washington, DC, was a segregated city. African-American and white people went to different schools, sat in different sections of restaurants and theaters, and did not mix socially. Even at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, a symbol of equality, African Americans had to sit in a segregated area. The newspapers run by whites rarely published stories about the positive achievements of African Americans, but they were only too happy to print stories about crimes in black neighborhoodswhether they were true or not.