Politics and Society in Urban Africa

Politics and Society in Urban Africa is a unique series providing critical, in-depth analysis of key contemporary issues affecting urban environments across the continent. Featuring a wealth of empirical material and case study detail, and focusing on a diverse range of subject matter from informal economies to urban governance, infrastructure to gender dynamics the series is a platform for scholars to present thought-provoking arguments on the nature and direction of African urbanisms.

Other titles in the series:

Alexis Malefakis, Tanzanias Informal Economy: The Micro-politics of Street Vending

About the author

Paul Stacey is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Denmark. He has published on a range of topics including traditional authority, colonial rule, local government reform, processes of marginalization, and the governance of revenues from extractive industries. Ongoing research focuses on agro-pastoralist groups adaptation strategies in contexts of climate change in rural Kenya, and the political economy of illegally extracted gold in Ghana.

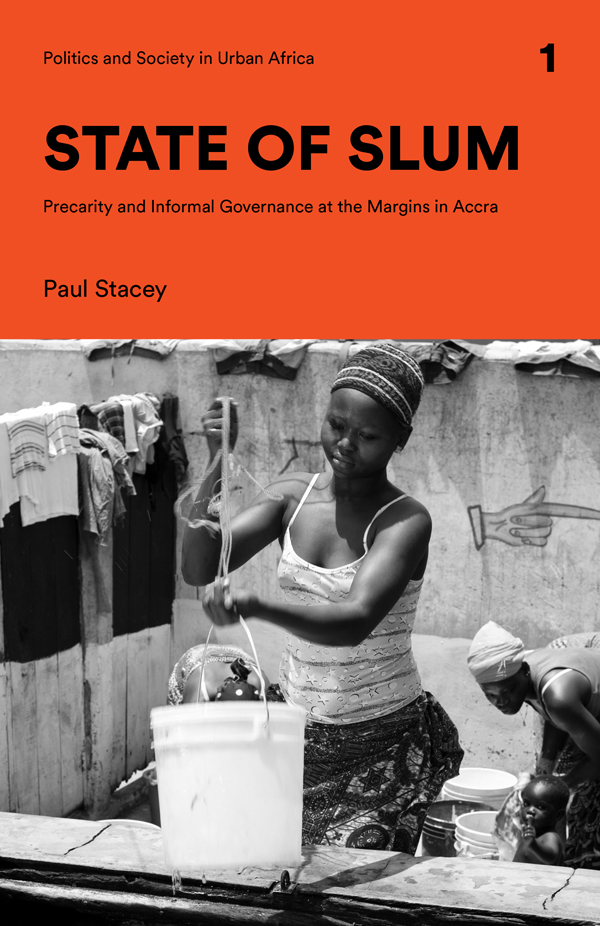

State of Slum

Precarity and Informal Governance at the Margins in Accra

Paul Stacey

State of Slum: Precarity and Informal Governance at the Margins in Accra was first published in 2019 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK

www.zedbooks.net

Copyright Paul Stacey 2019

The right of Paul Stacey to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Typeset in Plantin MT by seagulls.net

Index: Rohan Bolton

Cover design: Burgess & Beech

Cover image Nyani Quarmyne / Panos

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78699-204-8 hb

ISBN 978-1-78699-205-5 pdf

ISBN 978-1-78699-206-2 epub

ISBN 978-1-78699-207-9 mobi

To the unsettled everywhere

Contents

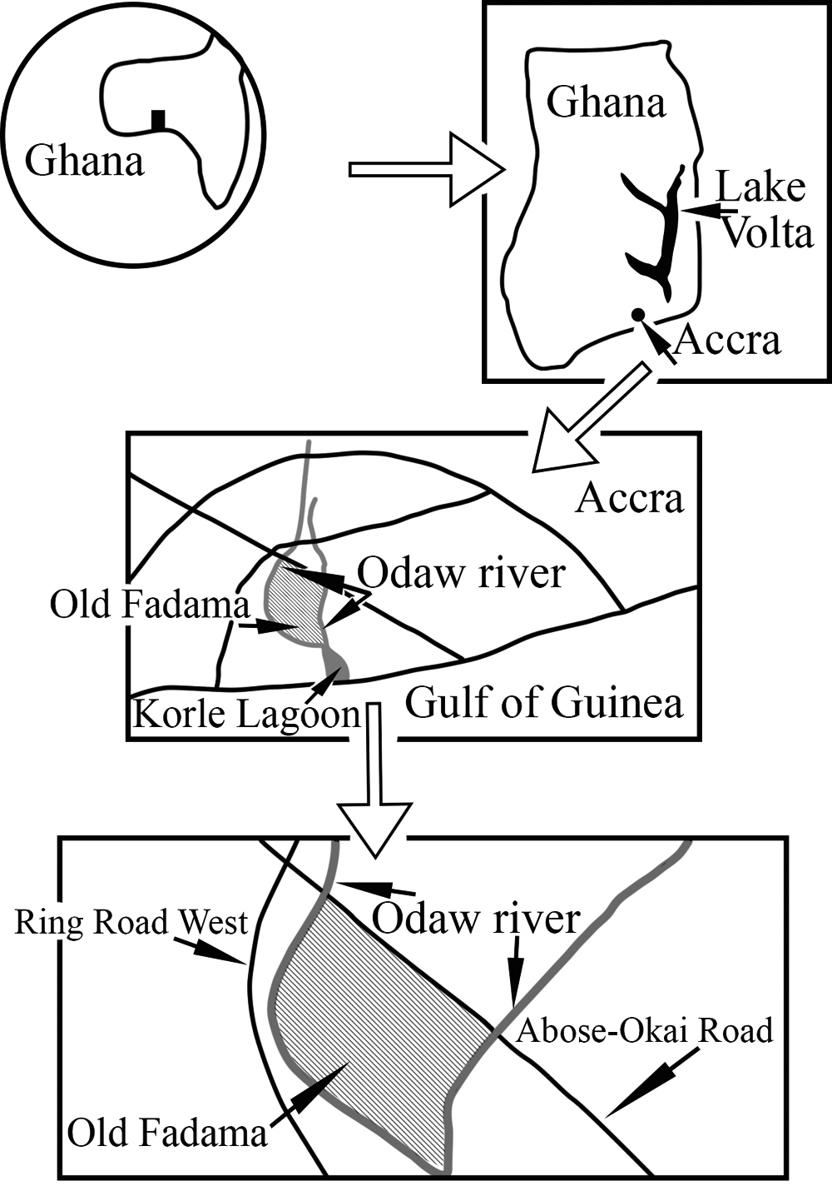

Sketch map of study area

The idea for this book originated from Christian Lund as we ate chicken and rice with shito sauce in an Accra hotel in January 2016. This was after another very hot day trudging around Old Fadama talking to all kinds of people and taking in as much as we could. Christian scribbled an outline for the chapters on the back of a napkin, and I nodded enthusiastically in agreement while thinking I will never be able to do that. So, the biggest thanks go to Christian for implanting the idea, and providing constant encouragement along the way (and for paying for the chicken).

Thanks to the Rule and Rupture European Research Council research group, directed by Christian from the Department of Global Development, Institute for Food and Resource Economics (IFRO) University of Copenhagen. Especially in the early stages, the group provided very useful advise and support, so thank you Penelope Fay Anthias, Rune Bolding Bennike, Jeremy Campbell, Michael Eilenberg, Eric Komlavi Hahonou, Kasper Hoffman, Inge-Merete Hougaard, Veronica Gomez-Temesio, Prathiwi Putri, Mattias Borg Rasmussen, Jesse Ribot, Nandini Sundar, and not least Tirza Julianne van Bruggen. Also at IFRO, I want to thank Iben Nathen for encouragement and support. In Ghana, a big thanks go to Ben Asunki and Sofie Yung Mitschke for their invaluable research assistance and constant good company, and of course all the people in Old Fadama I met and talked to, and who kindly shared their experiences with me. Thanks to the Independent Research Fund Denmark (IRFD), Social Sciences (FSE), for financing the project as an Individual Post Doc grant, and without which the book would not have materialized.

Sections of two chapters have appeared in different forms elsewhere and I want to thank Cambridge University Press for granting permission to reproduce them here: parts of ), In a state of slum: governance in an informal urban settlement in Ghana, Journal of Modern African Studies , 54(4): 591615.

Many thanks to Mike Kirkwood for the unenviable task of improving the language, Colin Dutnall for making the maps, and the public libraries in the Municipality of Copenhagen, for providing a quiet place to write. Thanks to Ken Barlow and Amy Jordan at Zed for help and support, and a big thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for providing substantial, and very useful comments and suggestions for improvements.

And special thanks to Pernille and Alice.

All omissions and errors are my responsibility entirely.

Paul Stacey

Copenhagen, September 2018

In June 2014 a celebration in the large informal settlement of Old Fadama in Accra centred on the opening of a community-driven bakery and an adjoining local NGO that was to offer legal advice to residents. It was a proud moment for Frederick, an Akan-born migrant, local entrepreneur and self-made NGO director who had worked diligently to raise seminal funding for the projects. The new buildings are situated on land that decades ago was grassland and swamp. In the 1960s it was claimed by government but has never been formally developed. Today, after years of sporadic settlement, improvised land filling and building, the area comprises a bustling thirty-hectare site of ad hoc constructions where about 80,000 people live.

Since the settlers were served with an eviction notice in 2002, Old Fadama has come to be known as the largest illegal slum settlement in Ghana. The site is made up of thousands of mostly single-storey, tight-knit, makeshift dwellings, micro-enterprises, kiosks and stalls (). These are linked, broadly, by a handful of roadways, but mainly by a labyrinth of narrow alleys just wide enough for people to pass abreast. Although the eviction order means that all building activities and residences are technically illegal, physical development of the site has continued more or less unabated over the last thirty years or so, contributing to Old Fadamas emergence as an integral part of the capital city. Yet the sites illegal status meant that the opening of the bakery and NGO was celebrated by some as an act of defiance by Old Fadama against an unaccommodating and unhelpful state. And, for many onlookers, the local projects exemplified a high level of resourcefulness that countered popular depictions of Old Fadama as a dangerous, squalid and uncontrollable place that should be demolished.

Close neighbours of the projects were especially proud of the new bakery, where vocational training is offered for up to fifteen young, susceptible girls. One neighbour of the project talked of few viable opportunities in the area, other than carrying head-loads, that were available to the young, uneducated girls, and that some would probably have ended up working as prostitutes if they had not gained a place in the project. The event brought a brief interval in which the residents of Old Fadama could disregard the nagging issue of their status as squatters and take pride in the demonstration of local development and inventiveness. Among the notables present at the ceremony were the vice-consular representative of the Australian High Commission to Ghana, which partly financed the projects, and representatives from the United Nations Development Programme and Amnesty International. The centrepiece of the occasion was the unveiling of a plaque by a Justice of the Ghana High Court. Some time afterwards I talked to Frederick, who explained his motivation for the projects in the context of his life in Old Fadama: