2015 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Tunisia: A Successful Revolution? reprinted by permission of Foreign Affairs, (September 17, 2013). Copyright 2013 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. www.ForeignAffairs.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

African renaissance and Afro-Arab spring : a season of rebirth? / Charles Villa-Vicencio, Erik Doxtader, and Ebrahim Moosa, editors.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62616-199-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-62616-197-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-62616-198-6 (ebook)

1. AfricaPolitics and government1960 2. Arab Spring, 2010 I. Villa-Vicencio, Charles, editor. II. Doxtader, Erik, editor. III. Moosa, Ebrahim, editor.

DT30.5.A36567 2015

960.3312dc23

2014027265

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

16 15 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 First printing

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Trudi Gershenov Design.

Foreword

The Arab Reawakening

An African Renaissance Perspective

THABO MBEKI

The year 2011 began with popular uprisings in the Arab world that started in the African Maghreb and Egypt. Described by some as an Arab Reawakening, we must answer the question whether, in reality, these uprisings do not also represent an African Reawakening.

Those of us committed to the renaissancethe rebirth of Africahave an obligation to understand what the popular uprisings in the African Maghreb and Egypt mean in the context of that renaissance.

Simply put, do the uprisings advance or retard this African rebirth?

One of the central objectives of the African Renaissance is the creation of the necessary space for the peoples of Africa to determine their destiny. The renaissance visualizes a democratic Africa, consistent with and focused on the objectivethe people shall govern! It will be a genuine renaissance only if it is the product of the conscious activity of the African masses across their various racial, ethnic, class, gender, and other social divides.

Surely we should understand the concept and practice of reawakening as an expression of the social processes according to which the masses of the people act in the political sphere as conscious and purposeful determinants of their own destiny, committed to fashion the nature of their societies through their own actions.

The African Renaissance should be a manifestation of an African Reawakening, while the reawakening should serve as the motive force for the achievement of the renaissance.

In what sense then should we promote the African Reawakening expressed in the popular uprisings in the African Maghreb as an integral part of the African democratic revolution?

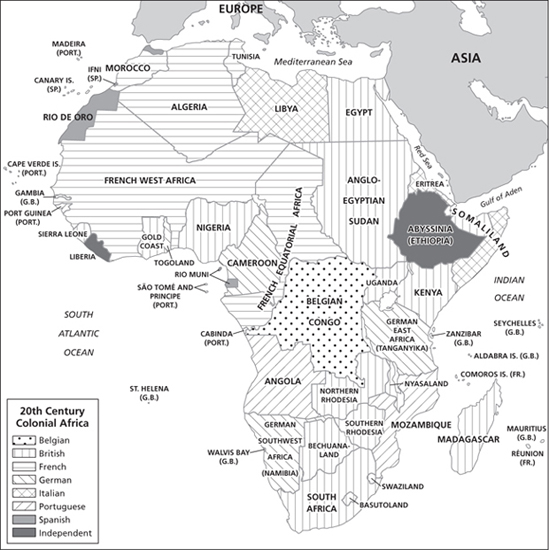

The historic African struggles for liberation from imperialist and colonial domination sought to achieve both national independence and the transfer of power to the peoplethat is, genuine democratic rule. Accordingly, these struggles were an expression of the commitment of the African masses to achieve their own national democratic revolutions.

As Africans we are very familiar with our own history, which is littered with many instances during which the national democratic revolutions were subverted and aborted, including through military coups and the establishment of dictatorial governments through other means.

In all these instances, when the national democratic revolutions were compromised, inevitably state power was used not to advance the interests of the people as a whole but fundamentally to serve the interests of a narrow national ruling elite, which would invariably ally itself with foreign interests determined to achieve their own objectives, regardless of the fate of the African masses.

We can therefore say that the crisis of governance in Africa during years of independence, with all its consequences, developed from the subversion or abortion of the national democratic revolutions for which the African masses fought as they engaged in struggle to liberate themselves from imperialism and colonialism.

The popular uprisings in North Africa have affected particularly Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.

What is common to the politics of these three African countries is that the ruling group in each country had been in power for more than two decades before 2011 with no possibility to change this reality through democratic elections.

Effectively, the systems of governance established in this part of the African Maghreb and Egypt constituted a negation of the objectives of the African democratic revolution and were inimical to the achievement of the renaissance of Africa to the extent that they were constructed to prevent the masses of people in this part of the African Maghreb from shaping their own futures.

Surely, ordinary common sense must communicate the message that these systems could not have survived as long as they did if they were not buttressed by pervasive repression, consciously targeted at denying the people the right freely to express their will, and therefore to determine their destiny, which is a fundamental feature of the African democratic revolution.

The tenancy of the entrenched ruling elites in these North African countries could only be guaranteed by continued repression, which, inevitably, would lead to growing discontent and therefore ever greater repression.

In these countries we are dealing with masses of people who have experience as conscious actors in the struggle to determine their own destiny. They gained this experience in the struggles for independence against imperialism and colonialism, in efforts to reconstruct their countries as independent and democratic African states, and in the struggle for the liberation of the people of Palestine. Thus, the sustained abuse of state power to demobilize them as conscious agents of change, to perpetuate exclusive rule by particular elites, and therefore to subvert the national democratic revolution assumed that these masses would come to unlearn the lesson that they are makers of history.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.