Introduction

by James Michael Yeoman

It would be useful to reconstruct the historical truth of the events of July, distorted as it has been by the insolent assertions that traditionalists of all stripe have dared to proffer in statements and protests, even more useful if we consider the fact that history has never recorded such a powerful revolutionary movement in which the revolutionaries had put such sentiments of human decency into practice. Maybe such decency was its own punishment.

So begins The July Revolution , an analysis of the Tragic Week of Barcelona in 1909 by the anarchist publisher Leopoldo Bonafulla. While the Tragic Week has attracted brief flashes of historical interestmost recently around its centenary in 2009

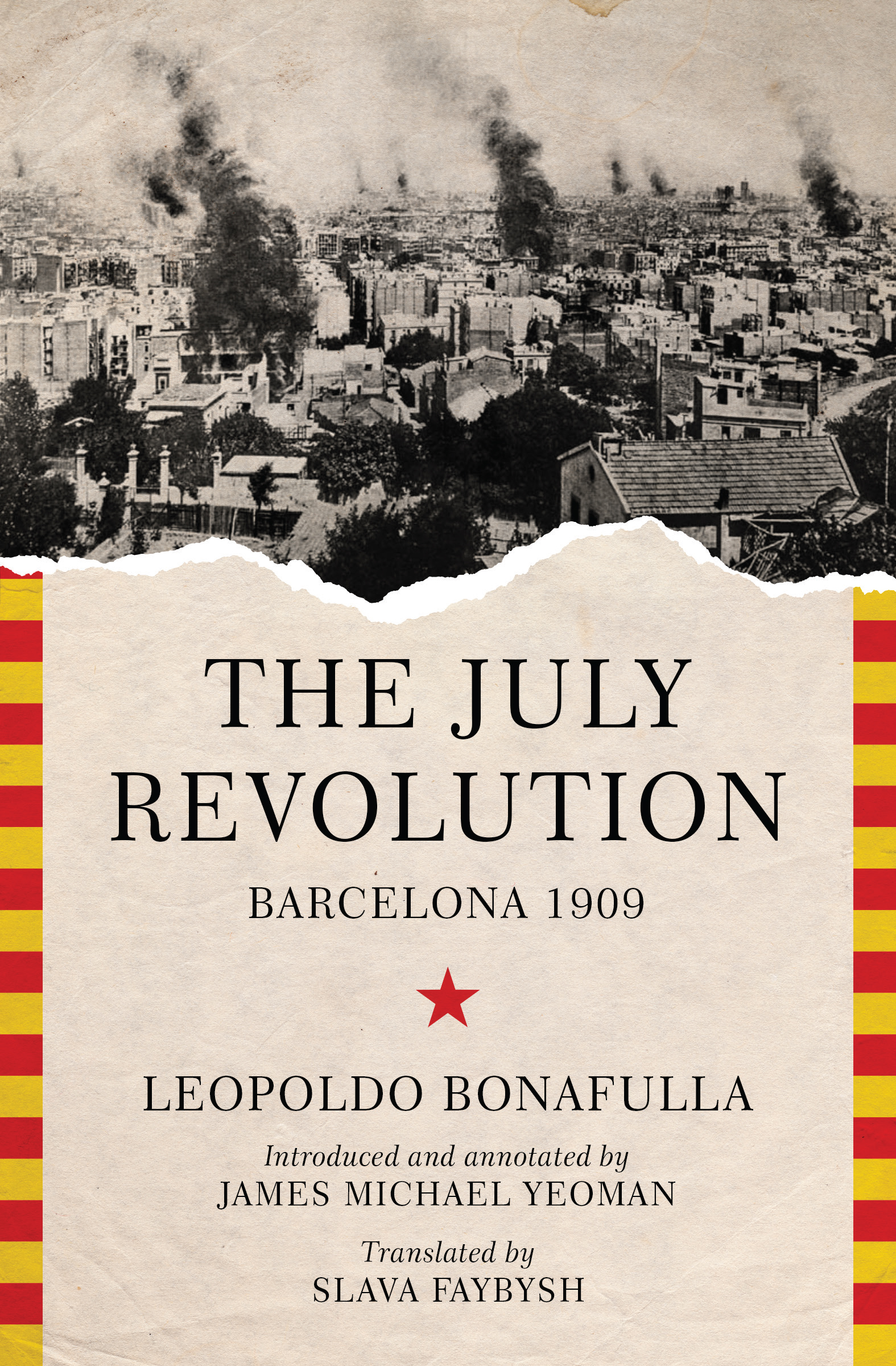

At its most basic, the Tragic Week was a popular insurrection which erupted across Catalonia in from 26 July to 2 August 1909. What began as demonstrations against the conscription of working class men to fight in a deeply unpopular colonial project in Morocco developed into a general strike across the region. Barcelona was the epicenter of conflict, as protesters clashed with security forces on the streets and began destroying the property of the Catholic Church. By the end of the week between a third and a half of Barcelonas religious buildings were burned by protestors in the most spectacular eruption of anticlericalism in Spain in almost a century. The repression that followed was brutal, as hundreds of anarchists, socialists, republicans, unionists, and freethinkers were arrested, imprisoned, and exiled. Most infamously, blame was shouldered by the radical anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer i Guardia, who was executed by firing squad on 13 October, following a trial widely regarded as a sham both in Spain and internationally.

Like any major historical event, the Tragic Week and its significance has been the subject of a range of interpretations. In her influential 1968 work The Tragic Week , Joan Connelly Ullman saw the events as primarily the result of radical republicans, who sought to direct the anger and energy of Barcelonas popular classes towards the Church and away from genuine social revolution.

In following decades, works by Joan Culla and Jos lvarez Junco have questioned both Ullman and Romero Maura, stressing that while the Tragic Week had no clear leadershipeither anarchist or republicanthe popular unrest can still be regarded as rational (Culla) and reflective of the distinctly modern mobilizing political cultures in the city (lvarez Junco).

It is not the intention of this introduction to settle these ongoing historiographical debates, but rather to situate the following piece within them, returning to the words and observations of a participant in the events and their aftermath. The historical value of Bonafullas work resides not in its historical accuracy: as noted by the translator of this work, the original edition published in January 1910 was rushed, full of errors of fact and slippages in spelling and typography. Bonafulla also assumes a great deal of knowledge on behalf of the reader, throwing in individuals, events and themes with little introduction, to the extent that approaching this work cold may leave the reader slightly bewildered. Nevertheless, this work provides something unique to anyone interested in the experience of popular unrest, revolutionary possibilities and state repression. Part eyewitness account, part reconstruction from press and legal sources, The July Revolution stands as the only extended contemporary anarchist piece of writing on the Tragic Week. As such, we see how a prominent radical publisher made sense of this event and the repression that followed: how the eruption of violence was seen as an inevitable response to the machinations of capitalism, the state and its colonial ambitions, and religion; how the Tragic Week did not have a leader but was rather the spontaneous impulse of unknown heroes amongst the Barcelona working class; and, crucially, how the Spanish state used the events of 25 July2 August to justify a ruthless repression against the anarchist movement, culminating in the execution of Ferrer. While Bonafulla may not be able to provide us with a wholly reliable account of what happened over these days, weeks, and months, few other sources can tell us how it felt to be a part of them and what they meant to an anarchist at the time.

I

The short-term origins of the Tragic Week lay in the grossly insensitive decision of the Spanish government to call up conscript reservists in early June 1909 following an escalation of conflict in Spanish-controlled Morocco.

The July Revolution begins with a discussion of this situation in Morocco, viewing the escalating conflict as the result of entangling business and imperial interests. It was, to Bonafulla, to the anarchist movement, and to a wide sector of Spanish society, a bourgeois war the result of a ruinous association of professional politicians and the banking elite (p. 46). The reader is introduced to a range of companies and figures in these opening passages, such as Compaia Norte Africana and the Count of Romanones, a wealthy Liberal businessman and newspaper proprietor, whose scheming with both French and German interests had resulted in the grotesque exploitation of Morocco. We are left in no doubt as to Bonafullas view on why the conflict arose in Morocco: beyond all the details, the political intrigue and international treaties, it was the transparent greed and egoism (p. 53) of the capitalist class that lay at the root of the call-up and the protest which followed.

With the Spanish parliament in recess, the only arena where popular anger at the call-up could be expressed was the streets. Bonafulla gives a vivid picture of these protests, stressing that they were both spontaneous and an absolutely just response to reservists being called to die in Africa (p. 55). This was no planned insubordination, nor an attempt by militants to provoke unrest, but rather the product of the despair of tearful, desperate people (p. 56).

Several groups now began to make plans to transform these demonstrations into a more concerted protest movement, and on Thursday 22 July a committee formed of anarchists, syndicalists, socialists, and republicans called a general strike, to begin on Monday 26. The strike was supported by the majority of Barcelonas working class, and soon spread to other towns in Catalonia. This politicalized industrial action rapidly developed into popular unrest in Barcelona, as barricades were erected in working-class barrios (districts), dividing the city between a popular insurgency of the left, freethinkers, and progressive educators on one side, and the army and quasi-military Civil Guard on the other. Clashes between these two blocs became increasingly violent, while the middle classes and ruling elites of the city closed their businesses and withdrew to their homes.

After paralyzing the citys economy and clashing with the forces of order, protesters turned against the Catholic Church. These attacks began on the first night of the Tragic Week, as men and women gathered by a Catholic School in the industrial district of Pueblo Nuevo, before destroying the nearby streetlights and torching the building.

Similar forms of anticlerical violence marked the first months of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, when once again hundreds of religious buildings were burned, artifacts destroyed, and the bodies of nuns dug up and paraded in streets across Republican Spain. Yet, unlike the violence at the start of the Civil War, the Tragic Week saw relatively few attacks on members of the clergy. By the end of the week one Marist Brother, one Franciscan Monk and one priest had been killed, alongside 104 civilians (both protesters and onlookers), two civil guards, five members of the military, one municipal policeman and one security guard. While clearly distressing for those that valued the Churchs architecture and material possessions, it is perhaps the focus of violence against property as opposed to people that led an anarchist like Bonafulla to depict the Tragic Week as a moment of revolutionary decency, conducted by brave crowds (p. 6768), acting in a correct, measuredall too measured manner (p. 114), while those few who engaged in murder or looting were merely isolated cases committed by the vile scum spawned by a perverse society (p. 67).