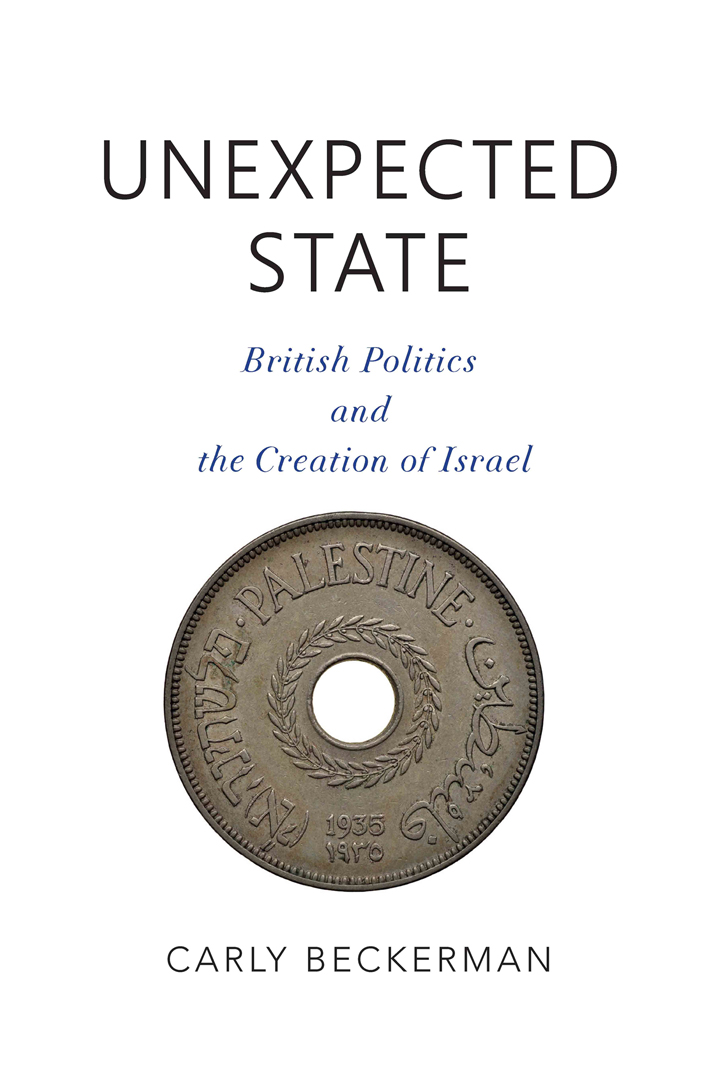

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2020 by Carly Beckerman

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-04640-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04641-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04643-7 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 25 24 23 22 21 20

D URING MY TIME researching and writing this book, I have benefited from the help of many individuals whose support deserves acknowledgment. First and foremost, I would like to thank Asaf Siniver for his ideas and insight and for challenging me to develop as a researcher. I would also like to thank Clive Jones, Anoush Ehteshami, Emma Murphy, and John Williams for their unwavering support.

I must also express appreciation to the Truman Presidential Library for providing a grant that allowed me to conduct research at the librarys archive in Missouri. In addition, thank-yous are owed to Lena Moral-Waldmeier for her research assistance and to the kind and helpful archivists at the National Archives in Kew, the Parliamentary Archives, London School of Economics Archives, Cadbury Archives, Durham Archives, United States National Archives, Truman Presidential Archives, and the United Nations Archives.

I would also like to say thank you to James Boys for his help in those early years, to my parents, Carol and Jon, for their boundless enthusiasm, and to my friends, Eleanor Turney, Beth Kahn, and Emily Thomas, for keeping me laughing (mostly at myself).

Finally, I would like to thank Andy Shuttleworth for his support and encouragement in difficult moments. I could not have finished this without him.

UNEXPECTED STATE

T HE BALFOUR DECLARATION is a document that, despite having been written in 1917, still stirs staunch pride or vehement disgust, depending on who you ask. It was a brief but momentous memo, ostensibly from (but not written by) British foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour. Although delivered to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild and published in The Times, Balfours note was, realistically, addressed to Jews around the world as it pledged Britains support for a Jewish national home in Palestine. Since British forces invaded the Holy Land a month after the letter was issued and only vacated Palestine in 1948 as Israel formally declared its existence, Balfours declaration has achieved a somewhat contradictory symbolic statusas a sign of Britains laudable achievement in, and devastating culpability for, the subsequent triumph of Zionism.

Former British prime minister David Cameron described this historic document as the moment when the State of Israel went from a dream to a plan, but it is generally considered throughout the Arab world to be Britains original sin. Supporting one viewpoint over the other depends on personal political preferences, but neither perspective is rooted in fact. The idea that Balfour signed a letter commencing the intentional and purposeful march toward Israeli statehoodin a territory that, at the time, was part of an Islamic empire and contained relatively few Jewshas become alarmingly unquestionable. Challenging this dichotomous history of British sentiment/animosity is always a precarious endeavor, but that is precisely what this book intends to do. Unexpected State aims, for the first time, to explain the how and the why behind Britains policies for Palestine. It argues that domestic politics in Westminster played a vital and inadvertent role in British patronage of and then leniency toward Zionism, allowing the British Empire to foster a Jewish national home and suppress Arab rebellion. Therefore, this book argues that the muddling through of everyday British politics was instrumental in conceiving and gestating a Jewish state.

By investigating how British governments endured moments of crisis with the representatives of Zionism, and how they dealt with indecision over the future of Palestine, it is possible to uncover a relatively clear pattern. The tumult of Westminster politics and Whitehall bureaucracy harnessed the idea of a Jewish presence in Palestine as a convenient political footballan issue to be analogized with and used pointedly to address other more pressing concerns, such as Bolshevism in the 1920s, Muslim riots in India in the early 1930s, and appeasement shortly before the start of World War II. The result was a stumbling, ad hoc policy journey toward Israels birth that never followed any centralized plan. Rather, for the British Empire of 1917, conditions culminating in Israeli independence were distinctly unlikely and unexpected.

Why such a situation occurred, however, is not exactly a straightforward inquiry, and the answer is relevant to a much wider discourse than merely the annals of obscure historical analysis. An ongoing search for peace in the Middle East cannot ignore how contemporary perceptions of the conflict are intimately bound to the parties understanding of their shared history. There are, naturally, multiple versions of this history, but, although the importance of Britains tenure in Palestine is hardly challenged, curiously few scholars have asked how British policy toward Palestine was made. This refers particularly to high policy decided by the cabinet in Westminster rather than the day-to-day activities of administering the territory, which was conducted chiefly through the bureaucracy of the Colonial Office.

What emerges within the relevant literature, instead, is a consistent recourse to stubborn, unsubstantiated myths about British intentions and motivationsmisconceptions that, in turn, fuel other attitudes that are distinctly unhelpful, such as the idea of an all-powerful Zionist lobby or the championing of Palestinian victimhood. This is explained extensively in , but the myths on trial here are broadly those that highlight British politicians personal feelings toward Jews or Arabs, as though these prejudices must have had a substantial impact on Britains imperial planning. The main problem with this thinking is that it is too easy to describe any number of contextual factors that may have influenced the direction of British policy. However, the evidence that bias drove or determined Britains relationship with Zionism and Palestine is frequently lacking. As the decision makers themselves are long dead and understandably unavailable for cross-examination, how then is it possible to determine, with any accuracy, what thought processes occupied their minds during the interwar period?

Bearing in mind this question, it is important to stress that some valid boundaries must be placed on the themes and issues explored in this type of investigation. Therefore, this book uses an innovative politics-first approach to illustrate four critical junctures of Britains policy making between the beginning of its occupation of Palestine in December 1917 and its withdrawal in May 1948. The following chapters argue that, contrary to the established literature on Mandate Palestine, British high policy reflected a stark lack of viable alternatives that left little room for consideration of personal biases, allegiances, or sentimental attachments to either Zionism or Arab nationalism during the tense moments when choices had to be made. This approach reveals how decisions about the future of Palestine were frequently more concerned with fighting narrow domestic or broader international political battles than preventing or dealing with a burgeoning conflict in a tiny strip of land on the Mediterranean.